Towers of glass and steel forest the downtown peninsula, creating neighbourhoods that crackle with the vibrancy of the world’s great urban centres

Doug Ward

Sun

CREDIT: Peter Battistoni, Vancouver Sun

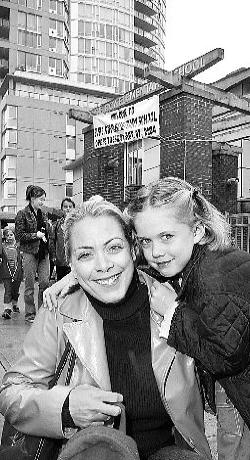

Monika Hobbs, with daughter Carina outside Elsie Roy elementary in Yaletown, says safety for kids is not an issue.

CREDIT: Ian Lindsay, Vancouver Sun

Shane Nelken is a musician who loves living in Gastown.

CREDIT: Ian Lindsay, Vancouver Sun

Paul LaFontaine has a billion-dollar view from his 16th-floor apartment in Metropolis, a 29-storey tower in Yaletown.

CREDIT: Peter Battistoni, Vancouver Sun

John Whistler has lived in the West End for 25 years and loves the area because it’s a ‘traditional neighbourhood.’

CREDIT: Mark Van Manen, Vancouver Sun

Elizabeth Atmore says living in the Coal Harbour neighbourhood is ‘like living in a resort next to a big city.

CREDIT: Ian Lindsay, Vancouver Sun

Jennifer Taylor lives in Yaletown and walks her West Highland terriers Robbie Burns and Murphy around Urban Fare and the Roundhouse Community Centre.

Jennifer Taylor is one of the Yaletown mommies. She’s so Yaletown mommy that not only does she walk with her kindergarten kid Andrew in tow — she’s also got her highland terriers, Murphy and Robbie Burns, to tie up outside the Urban Fare supermarket, or Urban Stare or Urban Glare, as she calls it.

“I moved here because I love living a cosmopolitan lifestyle. I just can’t seem to do the ‘burbs. Not good at it at all,” said Taylor.

“But I also need the safety of a neighbourhood because of my son.”

Taylor, a 40-year-old communications consultant, lives in Aquarius Mews, a perfectly named Concord Pacific highrise condo complex.

She has a bird’s-eye view of the epicentre of Vancouver’s new downtown residential lifestyle. But it’s not all leisure. Outside Urban Fare, business deals are made over cellphones or an espresso. Other participants in the scene discreetly cock their ears.

“And the ears are burning,” said Taylor. “This neighbourhood is a treasure chest of stories. And Urban Fare has become the quintessential point of Yaletown. It’s our gathering spot.”

Taylor’s so Yaletown mommy, she’s pitching a TV series on her shiny, happy ‘hood of glittering towers — pitching it in L.A.

One group of Americans already aware of the new Yaletown and the megaprojects along the north shore of False Creek and Coal Harbour are urban planners.

They’ve heard the buzz about what’s been called the Vancouver Miracle. About how Vancouver has the fastest-growing residential downtown in North America. Close to 40,000 people — people like Taylor — have moved downtown within the past 10 years.

Since the late ’80s, said former councillor Gordon Price, more than 150 highrises have risen within a mile radius of the central business district.

Downtown condo fever is so feverish that developers now market lifestyle as much as units. “Developers can be selling the same projects but they will market them differently by suggesting they represent dramatically different lifestyles.

“They are selling the cultural premium that’s based on the neighbourhood.”

He recalled a condo development on Georgia Street with a brochure that featured a mock-Soviet-realism photo of two young couples wearing bicycle helmets, looking upwards to a bright future of downtown living.

That future is now the present for Paul Lafontaine who lives in the Metropolis, a 29-storey Yaletown tower on the site of the venerable Canadian Linen building. Lafontaine grew up in a Toronto suburb, “and I’ve never wanted to live in a suburb since.” He takes the bus or walks to work downtown where he works as investor relations manager for a silver mining company. Lafontaine’s apartment, full of beautiful primitive art, is small at 775 square feet, but the northeast view of the downtown gives it an expansive feel. From his 16th-floor Yaletown condo, Lafontaine can see the suburbs in the distance, beyond the downtown highrise forest that surrounds his own tower.

He shops at Choices Supermarket which is just next door, has coffee at Triggiano’s, which is just around the corner, eats at the nearby Glowbal Restaurant and enjoys walking through the new and peaceful Emery Barnes Park just across the street.

About the downtown, Lafontaine says: “Vancouver is not a world capital. But the sense of vibrancy that one feels walking in downtown here is similar to some of the areas I’ve seen in New York, Chicago and San Francisco.”

LOOKING EASTWARD

That vitality has been sudden. Development in Vancouver’s central city has escalated at a pace far exceeding the expectations of city hall. The Yaletown/Downtown South area, for instance, is 10 years ahead of its original schedule. The Concord Pacific and Coal Harbour communities have also developed at unexpected rates.

There are 80,000 people living in the downtown peninsula — a figure expected to rise to 120,000 by 2021. The densification of the downtown has helped make the Greater Vancouver metropolitan region about 100-per-cent denser than Seattle.

The rhythm of downtown development has been so rapid that city hall fears the astronomic rise in residential land values — if not moderated — could bring redevelopment and gentrification to the West End and prompt conversion of many commercial buildings into condo towers.

To cool the pressure on the West End and the central business district, Vancouver’s chief planner Larry Beasley has told the development industry to shift its gaze eastward and help create an extended metropolitan core that would include redevelopment in Gastown, the Downtown Eastside, Chinatown, False Creek Flats and Southeast False Creek.

Ex-councillor Price said the downtown’s “centre of gravity will shift eastward so that the Grandview neighbourhood on the east side will eventually seem as close to downtown as Kitsilano.”

The mayor of San Francisco has heard so much about Vancouver’s vibrant inner city that’s he’s been trying to lure planner Beasley to his city so he can revitalize the troubled downtown there. So far he’s been unsuccessful.

Beasley has other downtown Vancouver neighbourhoods to help transform, including the Downtown Eastside, the impoverished, troubled neighbourhood that stands in vivid contrast to livable inner city neighbourhoods just blocks away. The success of the new megaprojects and Yaletown has exacerbated the problems in the Downtown Eastside by causing land speculation and disinvestment in existing buildings in the low-income neighbourhood.

In American cities, said Beasley, areas like the Downtown Eastside are either gentrified or become no-go ghettos. City hall wants to avoid both approaches and, using the lessons learned in developing other downtown neighbourhoods, bring a mix of housing and incomes to area.

“We now have experience in making mixed-use work with all kinds of people. And we know how to provide community infrastructure, and we can apply that knowledge to meet the needs of the Downtown Eastside. Plus our experience downtown gives us the nerve to go into the Downtown Eastside and work through the issues with the strong community that exists there.”

AN URBAN RENAISSANCE

In a recent book on the subject, The Vancouver Achievement, British author John Punter said Vancouver is no longer a setting in search of a city.

He described the False Creek North and Coal Harbour projects as the most ambitious high-density residential neighbourhoods on the edge of any downtown in North America in the ’90s.

Punter said that Vancouver has achieved “an urban renaissance more comprehensively than any other city in North America.”

Renaissance or not, Yaletown mommy Taylor, who has lived in Toronto and Penticton, said she feels more at home in her new neighbourhood than in any other place she’s lived.

“I feel safer here because it’s a community. The shopkeepers – they know our kids. They know my dogs. It’s very dog-oriented. It’s almost like you have to own a little dog to live here.”

Price, who until recently lived in Yaletown, said False Creek North initially seemed like a “giant stage set with nobody there.” This all changed with Urban Fare, which he said provided a place for locals to run into one another.

Kids and dogs. Neighbours meeting neighbours at the local supermarket and park. To Beasley, director of central area planning, the man most responsible for the Vancouver Miracle, they are all signs of the sense of community he hoped would evolve amid the highrises and townhouses in the new downtown neighbourhoods.

Beasley is aware of the knock on Vancouver’s residential mega-projects — that they cater to affluent and buff yuppies, have fetishized the cult of the view, promoted conspicuous consumption (see the occasional sale of $100 watermelons at Urban Fare) and created a high-density version of the Truman Show, the Jim Carrey movie set in an all-too-perfectly manufactured town.

But Beasley dismisses this criticism that the new neighbourhoods are too faux. “Every place was new once and every place shakes down in terms of the way people use it. Transformations occur over time and the environment becomes more organic.”

So he’s delighted that the new Concord Pacific and Yaletown neighbourhoods are increasingly less like resorts and more like real communities — not unlike those in other Vancouver neighbourhoods or in some suburbs.

Beasley is delighted that the downtown is having a baby boom and that city staff say there are more children now in the inner city than in Point Grey. He’s happy that a new school — Elsie Roy elementary — has opened in Yaletown. After all, when was the last time a new school opened in a Canadian downtown?

He’s pleased there are fewer cars commuting into the city every day than 10 years ago, with more than 60 per cent of all downtown trips now by transit, bike or on foot.

Beasley is also pleased with all the people he’s seen walking their dogs in the area around his townhouse near Beach and Hornby.

“Dogs are great generators of community. You have to take dogs out. This is how people meet.”

It’s how Taylor has met many of her neighbours. Which is something that shaped her answer when the prominent Canadian television mogul, Moses Znaimer, asked her for her take on Vancouver.

“I said it’s a small town with tall buildings. And that’s what my neighbourhood is.”

EMBRACING THE TOWER

Not so long ago, tall buildings, were not in favour — especially in Vancouver. Highrises, as popularized by the legendary French architect LeCorbusier and others, were seen as part of the modernist nightmare, a dystopia of skyscrapers, declining inner city neighbourhoods and car-clogged freeways.

Adverse reaction to highrises and freeways was what led to the mid-’70s demise of the Non-Partisan Association at city hall and the reign of the reformist TEAM under mayor Art Phillips.

Young activists like Mike Harcourt and Darlene Marzari helped stop the construction of a freeway that would have cut through Strathcona. Neighbourhoods were downzoned to protect them from developers seeking to erect highrises for super-profits.

“It was still possible to build some towers but it wasn’t easy,” recalled Price. “The cliche was that they were little concrete boxes filled with lonely, alienated people above crime-ridden streets.”

But over time, a perfect storm of factors led the descendants of the ’70s reform movement to embrace the tower as the form best suited to create a livable downtown in Vancouver.

There was an intense demand for housing in the period after Expo 86. Sprawl was limited by geography — the Pacific Ocean to the west, mountains to north and east, the U.S. border to the south. So it was natural that city planners looked towards the inner city.

Around the same time, there was a glut of office space throughout North America, and developers returned to housing.

Some began tearing down low-rise apartments in established neighbourhoods like Kerrisdale, prompting a public outcry.

Sensing an opportunity to meet the housing demand and protect single-family neighbourhoods, the city in the early 1990s developed its “living first strategy” to develop the margins of the downtown and waterfront megaprojects. The West End had prospered through the ’80s, showing that highrise living could thrive in the downtown.

Critical to the success of this shift was Vancouver’s deepening connection to Asia-Pacific markets and countries. Asian investment and immigrants helped accelerate the transformation of the downtown through the ’90s. The role of Hong Kong billionaire Li Ka-Shing in purchasing the former Expo 86 site and turning it into Canada’s largest real estate development project was the most obvious example of the Asian impact. Vancouver’s rise as a post-industrial world-class city attracted affluent off-shore buyers of high-end condos, many of them becoming second-homes in a postcard setting.

Gradually, condo developments proved popular with a new middle class of white-collar professionals who rode the economic boom of the ’90s. Professional people became over-represented in the inner city and under-represented in the suburbs — the reverse of what happened in most other North American cities.

DEVELOPERS GET RICH

The dominant architectural form in Vancouver’s new downtown — the tower with two- or three-storey townhouses at street level — was also unique. When pedestrians walked by they didn’t see the blank wall of a monolith — they saw a townhouse door or window or a shopfront. It was high-rise living with a human face.

Beasley said the tower-townhouse prototype — developed by local architects like Richard Henriquez, Paul Merrick and James Cheng — was a modernist form that provided the mixed-use vibrancy in Vancouver sought by anti-modernists such as urban theorist Jane Jacobs, who is a huge fan of Vancouver’s downtown.

The sky-high house prices on Vancouver’s west side also prompted many young professionals to look downtown.

“People were back into sleekness again,” said Price, “and into the image of modernity.”

The growing demand made condos the popular form for developers who then whipped the demand up further with successful marketing.

“Developers successfully changed the image of the apartment unit. Now they were selling granite countertops and lifestyle in a unit that was an investment as well as a home.”

Demand for downtown condos is on the up-escalator to this day, said Beasley, as “success begets success.”

Developer Michael Geller, who moved to Coal Harbour, finds the rise in values breath-taking. “I never believed that my old car dealership would be worth about $4 million.”

Among the factors cited by Geller are low interest rates, West End renters looking to own, investors looking for good return, and the “herd instincts” of developers.

“Someone once said developers make sheep look like free thinkers,” said Geller.

“Once one or two credible people go into an area, everybody follows. I met a fellow from Indonesia who’s developing in Downtown South. He heard everyone else was there and so he felt he should be there.”

The huge land appreciation that took place on the megaprojects, land previously zoned light industrial, gave the city leverage to use development-cost charges to extract money from developers for a host of amenities, including seawalls, parks, daycares and community centres. The taxpayer didn’t have to pay a dime but gained a more livable downtown.

“The basic reality of the economics of the Vancouver Miracle,” said Beasley, “is that the large development sites were originally of very low value and then, through public decisions, became very high-value.

“So the land-lift was huge and because of that we could leverage a lot of public goods and the developers could still get rich.”

And because much of the redevelopment occurred through megaprojects, the amenities came on stream quickly without having to be built up incrementally.

The downtown beat goes on and on. There’s money to be made by housing the tens of thousands of people who will want to live close to ground zero in the coming years. And so city hall has told the development industry to switch direction.

“I’ve been telling developers that the world is moving east and that’s going to be where your opportunity is,” said Beasley.

He sees the downtown — or the metropolitan core, as he prefers to call it — spreading incrementally east, through Gastown, Chinatown, the Downtown Eastside, the False Creek Flats and Southeast False Creek.

Beasley rolled out his vision of the downtown’s future in April during a speech to the Urban Development Institute. He told the developers there are fewer and fewer available sites for development in the downtown peninsula.

And he said the city intends to clamp down — at least in the short-term — on the conversion of commercial buildings to residential in the downtown core.

Beasley said the city currently has five inquiries from developers wanting to convert commercial buildings into housing to take advantage of the demand for residential.

Vancouver, Beasley said, cannot afford to lose its ability to provide commercial space when that market rebounds. The city’s strategy of providing both jobs and housing downtown would be undermined if commercial space dried up, creating a “downtown- as-resort” scenario.

Beasley said Gastown is the new Yaletown — a historic area being steadily transformed by new residential development.

“Water Street is already showing signs of its revival and within 24 months from today, Gastown will look and feel very much better than it does now.”

Beasley said Chinatown “is where Gastown was 18 months ago.” The city is expecting 10,000 new people to live in Chinatown — in both market and non-market housing.

Nevertheless, added Beasley, the city will allow the development of some market housing – probably “modest-cost” units and live-work units. The Woodward’s project is expected to be harbinger of what’s to come.

“There’s a lot of fear there because it’s a very fragile community. We will not support the wholesale displacement of that community. I mean, it’s not going to happen on my watch, and I don’t think it will happen on the next watch.”

Beasley said he believes the city can protect the Downtown Eastside’s low-income community while allowing a controlled amount of market and non-market gentrification to occur in the beleaguered neighbourhood.

“I believe you can, if you decide to. In most cases, people either don’t make a decision about it and so let the world unfold. Or they explicitly want it [widescale gentrification] to happen.”

Beasley said there is a market in the Downtown Eastside for “consumers who are more interested in living in an environment that is perhaps a little more edgy” — people who don’t want to live in highrise towers, prefer a historic setting and are willing to put up with irritants that many middle-class people might not tolerate.

‘PEOPLE CRASHING TOGETHER’

Developer Michael Geller said the future of the Downtown Eastside will affect the downtown’s move east. “The problems in the Downtown Eastside — its drug addiction, panhandling and property theft — are affecting downtown living. Not just in the Downtown Eastside but in other areas.”

The key is the arrival of young middle-class professional people into the area. “I actually think by having more of a mix that you have potential to dilute the concentration of very low-income people without having to reduce the number of very low-income people.”

The next area for development is Southeast False Creek, where the city plans to house 15,000 residents. One-third of these residents will be on low-income, another third middle-income and another third high-income.

This development will allow the downtown to wrap around False Creek with dense residential development on all sides. An official development plan is expected later this year.

The last section of the future downtown is the False Creek Flats, an area whose unstable geology restrained development pressure in the past. The two main anchors on the site are the Finning Lands parcel, which will become the focus for post-secondary institutions, and the area north of the Pacific Central Station, much of which has been purchased by St. Paul’s Hospital for future relocation.

Beasley said what will go between these two focal points has yet to be decided. Should it be a high-tech complex, a new live/work neighbourhood, a soccer stadium and sports centre, or a casino? All these proposals have been put forward.

While there will be debate over the future shift east, few will argue that density in these areas slated for redevelopment is a bad thing. There is a strong consensus in Vancouver now about density, which isn’t the case in other North American cities where, said Beasley, “people hate high density because it’s been badly done.”

The lesson of the Vancouver Miracle, says its main promoter, is that high density works — if done right. “I’m still a great believer that it’s just people crashing together that creates energy and ideas.”

DOWNTOWN DWELLERS:

The Sun’s Doug Ward talks to four inhabitants of the city’s core to find out why they love where they live.

A KIDS’ PLACE IN THE CITY

YALETOWN – It’s not so much that Monika Hobbs likes living downtown. It’s more that she likes living in Yaletown.

“I wouldn’t want to live anywhere else downtown. Yaletown has more of a European feeling,” said Hobbs.

It’s a reminder that the new downtown neighbourhoods are appealing to different markets and creating strong ‘hood loyalty.

She lives in a three-bedroom condo with her five-year-old daughter Carina and her American husband, Jeff, a software engineer who works downtown.

“I wouldn’t want to live around Gastown. It’s a totally different feeling. We get panhandlers here too, but it’s not too bad.

“But I wouldn’t want to live in Coal Harbour either. It’s too sterile. It doesn’t have character.”

Hobbs and her husband bought their three-bedroom condo about three years ago. They were fleeing the suburban experience of Silicon Valley outside San Francisco.

“We lived in suburbia and hated it. It was boring. You had to drive everywhere. My husband can now walk to work, we hardly ever use our car. Whereas in California you spend most of the day in the car.”

Hobbs said downtown San Francisco didn’t have the same livability as downtown Vancouver. There was too much poverty, not enough safety or kids.

“There’s so many kids around here in Yaletown. It’s like there’s some in the water. A lot of young children, lot of babies in strollers, lot of pregnant moms.”

Safety for her child is not an issue here. “To be quite honest, the only time I ever hear something happening to children, it’s out in the suburbs. Not in the downtown.”

‘MUCH MORE CHARACTER’

GASTOWN – Shane Nelken lives in the less-safe Gastown area, but is willing to put up with the grit because of the neighbourhood’s historic look and growing sense of community.

“I don’t have a car, so it’s helpful to be central. But I’m also attracted to the history here. I like being in one of the older neighbourhoods. It has so much more character than a Yaletown or a Kitsilano.”

Nelken, a rock musician, is a member of the Vancouver power-pop band A.C. Newman, whose front-man, Carl Newman, was recently acclaimed in the New York Times Magazine. He lives with his girlfriend, Karen MacIntosh, in a condo complex near Alexander and Main.

They recently purchased a new live/work condo on the ground floor of the old Koret swimwear factory on Cordova, which is undergoing renovation.

He’s happy to be moving into a heritage building that will be mostly preserved.

“I’ve always loved the neighbourhood and I see the potential as well.”

Nelken is not unmoved by the human misery caused by the poverty, drugs and mental illness around him.

“One of the most tragic things about living down here is that you have to shut out a lot of the stuff. You are confronted by human tragedy every time you walk out the door.”

Still, he loves the sense of community emerging in Gastown. He’s optimistic about coming redevelopment and he doesn’t think gentrification is bad so long as enough housing is protected for low-income people.

“But I don’t think you are ever going to fully eradicate a lot of the problems … Nor do I want that to happen. I kind of belong down here.”

A 15-MINUTE WALK TO WORK

WEST END – Amid the new migrants to the downtown are people who were sold on living there decades ago and moved to the West End. People like John Whistler, who has lived there for 25 years.

“I just love the downtown, but I’m really speaking of the West End. It’s a traditional neighbourhood, while Yaletown and Coal Harbour are emerging neighbourhoods without that neighbourhood feel. But that will come in 15 or 20 years.”

Whistler lives alone in a condo near Comox and Denman. He walks to his job at Duke Energy on West Georgia.

“For me it’s a 15-minute walk to work. I don’t own a car and don’t need a car. Everything that I need is within walking distance or a short taxi ride away.”

Whistler estimates there are about 50 restaurants within three blocks of his apartment.

“I would say that most people I meet in the West End like the West End and particularly like it because it is safe walking on the street at any time of the day or night.”

His says the West End has more diversity in income groups, housing types and retail services than the new downtown neighbourhoods.

“Coal Harbor and Yaletown have a bit of a mono-culture, with brand-new condo buildings, all the same style, and attracting the same demographic group.

“In the West End, the demographics are more diverse. And there are more kids now than when I first moved here.”

Many of the kids belong to immigrant families from Eastern Europe who prefer downtown apartments to life in suburbia.

Nor has Whistler any plans to move elsewhere.

“Even if I won the lottery, and I don’t buy tickets, I’d just buy a nicer apartment in the West End.”

GREAT FOR A SINGLE PERSON

COAL HARBOUR – Elizabeth Atmore loves her new Coal Harbour residence, but the real estate developer isn’t sure she could live elsewhere in the downtown.

“It’s like living in a resort next to a big city. I love being near Stanley Park, riding my bike on the seawall, using the pitch-and-putt.”

When Atmore has a business meeting downtown, she walks along the Coal Harbour seawall, past the Pan Pacific Hotel, and into the city.

She lives in Bayshore Gardens, located in front of the Westin Bayshore. Atmore moved to the new upscale neighbourhood in 1999 after going through a separation.

She initially rented from an owner who lived in the Bahamas, but then, following completion of her divorce, decided to become an owner.

“It’s great for a single person. In the evenings you can get out with fun friends and there are so many places nearby to relax.”

The views are a big part of the Coal Harbour experience.

“I just love waking up in the morning and looking out the window. I see the North Shore, the marinas, the float planes coming in. The birds fly by.

“And what’s often nice in the morning is the pink reflection of the sunrise on the harbour.”

Atmore likes the proximity to Robson and Denman. “I have restaurants right on my doorstep. I have grocery shopping, salons, even a little hardware store.

“It’s a bit like a New York lifestyle but with the advantage of the serenity of nature.”

Atmore has taken art classes at the Coal Harbour community centre, eats at nearby cafes and takes her grandchildren to to the Second Beach pool.

She wouldn’t move to Yaletown. “It doesn’t have the beautiful trees. It doesn’t have nature. It’s too much concrete.”

LIFE IN THE BIG CITY:

Downtown Vancouver residents are wealthier and more likely to be married than their West End neighbours.

DOWNTOWN

Married: 32%

Live alone: 31%

People aged 75-plus: 2.4%

Average family income: $81,739

Average dwelling value: $260,743

Individuals per 1,000 stating ‘no religion’: 432

WEST END

Married: 22%

Live alone: 41%

People aged 75-plus: 5.7%

Average family income: $64,644

Average dwelling value: $212,936

Individuals per 1,000 stating ‘no religion’: 432

Source: Statistics Canada and Vancouver Sun

© The Vancouver Sun 2004