Growth charts of Vancouver

Michael Kluckner

Sun

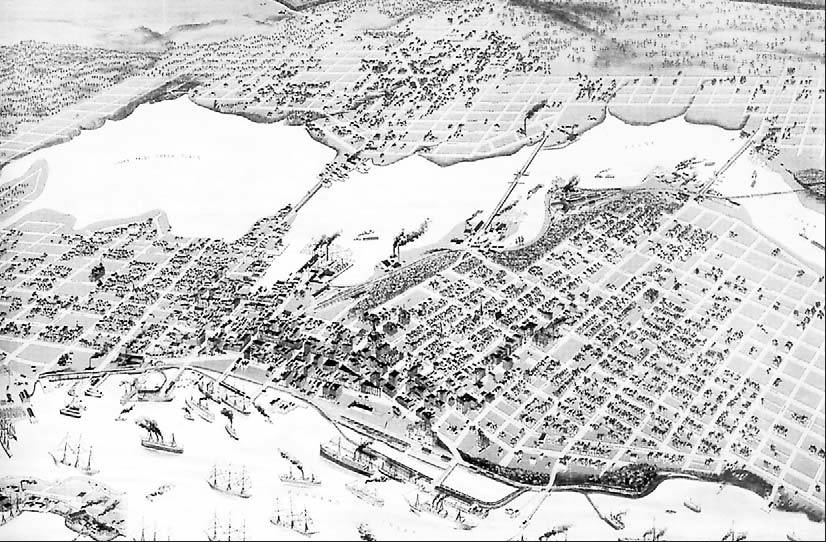

FROM HISTORICAL ATLAS OF VANCOUVER AND THE LOWER FRASER VALLEY, BY DEREK HAYES A ‘bird’s-eye’ map published in 1898 showing Burrard Inlet (foreground) and False Creek with bridges at Main, Cambie and Granville Streets.

CREDIT: Peter Battistoni, Vancouver Sun Files Derek Hayes: A career of fiinding old maps and explaining their significance

On the increasingly crowded shelves of Vancouveriana, it’s a rare book that presents something truly new. Yes, there will probably be book-length biographies of people who once merited only a two-paragraph obituary, and there will be further gleanings of archival photo collections of the city in its “golden age” a century ago. But it’s getting harder to find new, relevant material, especially linking past events with current challenges.

Derek Hayes, a geographer trained in England and at the University of B.C. and a former planner with the City of Vancouver, has made a career of finding old maps and explaining their significance to a general audience. Publishing mainly with Douglas & McIntyre, he designs and lays out his own books, of which this is the eighth.

Previous works have illuminated Canada and the Arctic and celebrated the explorations of pathfinders such as Alexander Mackenzie. His Historical Atlas of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest (Cavendish, 1999) set the stage for the current work, showing maps of ever-increasing detail as explorers charted the West Coast and the future site of Vancouver.

In Historical Atlas of Vancouver and the Lower Fraser Valley, his enthusiasm tumbles out of the captions: “Superb,” “magnificent” and “delightful” are recurring adjectives. And he assumes little historical knowledge on the part of his readers: Edward S. Curtis, for example, is described as “a famous photographer of native life.”

The books are indeed historical atlases, but they might more accurately be described as history books that use old maps, bird’s-eye views and images such as promotional real-estate advertisements to illustrate a text divided into short topical chapters.

Two previous books that trod some of the same ground come to mind. Bruce Macdonald’s Vancouver: A Visual History (Talonbooks, 1992) used a map template of the city, adding layers of historical development to it, decade by decade, from the pre-contact 1850s to the 1980s. The lavish Sto:lo-Coast Salish Historical Atlas (D&M, 2001) illustrated the Lower Mainland and Fraser Valley with complex maps presenting the region from the native point of view.

Hayes’s book begins with two maps of pre-contact Vancouver — one drawn by archivist Maj. J.S. Matthews using information gathered from native elders in the 1930s, the other reproduced from the Sto:lo atlas.

Several pages follow from surveys by Spanish explorers, Capt. George Vancouver and fur traders, including Simon Fraser. Until the late 1850s, they all show the downtown peninsula as an island, presumably due to the high-tide slough, known as the canoe route, that once connected False Creek to Burrard Inlet near Columbia Street.

Finally, in the detailed 1859 surveys by George Henry Richards of the HMS Plumper, the downtown and False Creek (including the sandbar that was enhanced to create Granville Island) emerge accurately.

Pages of maps and text describe the orderly street grid imposed on the Fraser Valley by the Royal Engineers, the drawing of the international boundary, and the development of diverse Valley communities, from White Rock to Chilliwack. Canneries along the Fraser River get a couple of pages, including a detailed map of the Steveston waterfront in its 1897 heyday, drawn by civil engineer Charles Goad.

Hayes reproduces Maj. Matthews’s sketch map showing how the infant Vancouver was destroyed in the great fire of June 13, 1886. Across the fold is Canadian Pacific Railway surveyor Lauchlan Hamilton’s definitive plotting of downtown Vancouver from the following year. If you ever wondered why Hastings Street takes a jog at Burrard or why there are flatiron (slice-of-pie-shaped) building sites in Gastown, this is the page for you.

Enter speculators and realtors, hot on the heels of the CPR. All of the skills of commercial artists and engravers were brought to bear on the task of selling the new city to potential residents and tourists. A generation before the first aerial photographs, artists such as C.H Rawson and H.E. White drew breathtaking bird’s-eye views of the city, annotating them with the kind of visual and textual detail that rewards lengthy study.

Other drawings illustrate massive industrial schemes, such as the docks and works proposed for the entire western foreshore of Richmond in 1911, and the CPR’s 1917 plan for docks and a rail terminus on Kitsilano Point. These show an “unbuilt Vancouver” that would have destroyed the natural environment on which the region’s modern self-image is built.

If the city had a guardian angel, it was surely economic recession that so often nipped these wild plans, whether industrial or architectural, in the bud. Apropos of such hard times, Hayes has dug out Maj. Matthews’s 1934 map of the homes of Vancouver‘s 27,583 welfare recipients: Only a few dots speckle the expensive neighbourhoods south of 16th and west of Main.

Historical Atlas of Vancouver and the Lower Fraser Valley is especially noteworthy for its meticulous coverage of Vancouver in the 1950s and ’60s, when it had its close call with freeway-induced disaster. Beginning with civil defence and evacuation maps from the Cold War, Hayes presents the various plans for highways radiating from the city. He reproduces images from the Vancouver Transportation Study of October 1968, which show starkly what would have happened to the waterfront, Chinatown and Gastown if citizen protests hadn’t stopped them.

A final section brings the region more or less up to date, with images from the Livable Region Strategy that still (subject to the provincial government’s flawed Gateway scheme for twinning the Port Mann Bridge, etc.) provides a vision for the future.

One shortcoming, in my opinion, is the cursory attention given to Vancouver‘s historic fire insurance atlases, especially those done by the above-mentioned Charles Goad & Co. in the early years of the 20th century. Block by block, building by building, they showed house footprints and the lay of the land with an astonishing level of detail, including annotations such as “cabins” and “Chinese” that bring the lost city alive.

A later set, the 14-volume Insurance Plan of Vancouver, captured the city in 1955 — the beginning of the modern era. Hayes reproduces a few pages — showing, for example, Ballantyne Pier in 1925 — but says little about the atlases themselves, which must surely be the most comprehensive and detailed sets of maps ever made of the city.

This large-format book reproduces more than 370 original maps in just 192 pages. It’s a tight fit, leaving some pages quite cluttered. As a collector/historian, Hayes was obviously faced with the conundrum of what, if anything, to omit and still leave room for a general narrative, lengthy captions and photographs (some of which seem redundant).

A few of the maps and drawings are so small as to be effectively illegible, and not strong enough graphically to justify the space they occupy. Sometimes a picture isn’t worth a thousand words.

I wish Hayes had the space authors got 20 years ago, when a collector/historian like Henry Ewert could spread his Story of the B.C. Electric Railway (Whitecap, 1986) over 336 pages and still publish it at an affordable price.

This is a challenging book to read. You need good white daylight and, probably, a magnifying glass to get full value from many of the images. But it’s worth the effort.

Michael Kluckner’s most recent book is Vanishing British Columbia.

© The Vancouver Sun 2005