After 400 years of deadly excursions, sea may soon be navigable

Randy Boswell

Sun

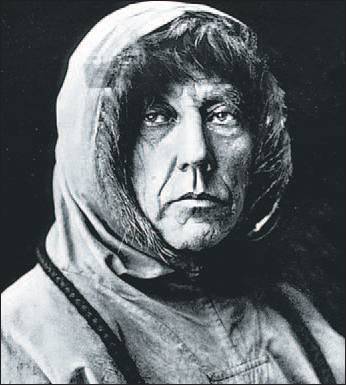

VANCOUVER SUN FILES Norway’s Roald Amundsen became the first explorer to traverse the Northwest Passage, raising alarms in Canada.

Stunning for its polar seascapes, rich in history and resources, yet still one of the planet’s most mysterious places, the Arctic Ocean is an immense but largely overlooked part of Canada.

It is immensely important, too — even hailed as a “new Mediterranean” by those who envision this country as the key portal to a new circumpolar sphere of geopolitical power in an age of climate change.

But the sea that didn’t make it into our national motto remains, for now, at the margins of Canadian consciousness, despite its sprawling presence across our northern frontier, despite its increasing strategic significance, despite the fact that much of our early history unfolded there — and much of our future is expected to.

The Arctic Ocean is the ice-lined edge of home for tens of thousands of Canadians — mostly Inuit and other first nations people — and the fragile domain of polar bear and narwhal, signature species of the North.

And it is, undoubtedly, a sea of superlatives.

It includes the great Arctic archipelago from Banks Island in the west to Baffin in the east to Ellesmere in the north — a 1.3-million-sq.-km. swath of land, ice and water comprising the world’s largest group of islands.

Its mainland shore stretches some 30,000 km from the northwest corner of the Yukon to the tip of Labrador peninsula, sculpting the saltwater coasts of the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec along the way.

Yet scientists have described this Arctic vastness, as recently as 1990, as “Canada’s missing dimension” — a little-understood ocean, with an almost unexplored seabed, swirling around largely unstudied lands.

Mythologized in the 19th century as a fatally inhospitable corner of the planet, the traditional image of the Arctic as a frozen wasteland is only now melting away — and still more slowly than the permafrost and polar ice are thawing from global warming.

“The Arctic is in the process of transformation from a land of the imagination to a place in the real and everyday world,” archeologist Robert McGhee has written in The Last Imaginary Place, A Human History of the Arctic World. “This clear-sighted view of the Arctic will be needed if the peoples to whom it is home, and the national governments that claim sovereignty in its territories, are to cope with the problems that are converging on the region from several directions.”

The transformation McGhee identified is being hastened, above all, by the increasing likelihood of a reliably navigable Northwest Passage in the near future — with oil tankers and other freighters plying an unfrozen ocean.

Remarkably, the prospect of a clear sea route across the top of North America was the original impetus for exploring Canada’s Arctic waters more than 400 years ago.

Frobisher, Hudson, Davis, Baffin — the English sailors whose Arctic expeditions are still prominently commemorated on Canada’s maps — failed in their quests for a shortcut to China.

But they did chart a path toward the heart of North America. And fur-trading forts along Hudson Bay gave the British their first serious foothold in the future Canada, and set the stage for the European settlement and development of the old northwest.

Seeking an Arctic sea passage remained an obsession for British, American and Scandinavian explorers throughout the 1800s, as the ill-fated Sir John Franklin and a steady stream of would-be rescuers sailed to glory or doom throughout the ice-choked archipelago.

But even by the early 1900s, as Sir Wilfrid Laurier was famously declaring that the 20th century would belong to Canada, it still wasn’t clear whether the Arctic islands did.

In 1902, the Norwegian explorer Otto Sverdrup discovered three large islands west of Ellesmere. And in 1906, the year “From Sea to Sea” had its first ceremonial use in Canada, Norway’s Roald Amundsen became the first explorer to traverse the Northwest Passage — a feat that raised further alarms about Canada’s territorial claims in the North.

Ironically, it was not until 1921 — the year Canada adopted A Mari usque ad mare as its motto — that Icelandic-Canadian explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson truly awakened the nation to its forgotten Arctic Ocean frontier.

It was his publication of The Friendly Arctic — an account of the polar expeditions during which Stefansson led several crewmen to their deaths but discovered some of the world’s last major land masses — that nudged the North into the Canadian psyche.

THE THIRD SEA:

Northern aboriginal leaders and top Arctic scientists are echoing a call by the three territorial premiers to rewrite the national motto to reflect the true vastness of the country and formally declare Canada a nation that extends ‘from sea to sea to sea.’

The premiers — Dennis Fentie of the Yukon, Joe Handley of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut’s Paul Okalik — say it’s time to amend A mari usque ad mare, the Latin version of “From sea to sea” that appears on the country’s coat of arms.

The change, they say, would acknowledge the country’s Arctic Ocean frontier along with its Atlantic and Pacific coasts, and symbolically assert Canadian control over the Northwest Passage and other disputed sites in the North.

Source: CanWest News Service

© The Vancouver Sun 2006