They’re almost identical to the real thing, experts warn

Peter Wilson

Sun

Security expert Ron O’Brien, senior analyst at Sophos, which operates a major spam lab in Vancouver, said phishers just seem to get better and better at what they do. Photograph by : Vancouver Sun Illustration

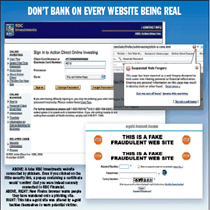

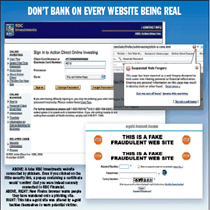

It looked like a genuine RBC Investment site on the Internet last week. All the logos were there. All the links worked — even the ones that led to warnings about supplying your password to digital crooks.

And if you clicked on the little security lock, a pop-up containing a certificate issued by Verisign would confirm that you were indeed securely connected to RBC Financial.

But — no surprise to more sophisticated Net users — the site was a fake, as confirmed by RBC Financial.

A group of digital crooks, apparently in Kyiv, Ukraine, was “phishing” — as the term puts it — for suckers. The unwary had been lured by an e-mail telling them “due to the recent update of the servers, you are requested to please update your account info at the following link.”

Security expert Ron O’Brien, senior analyst at Sophos, which operates a major spam lab in Vancouver, said phishers just seem to get better and better at what they do — to the point where they’re now creating almost completely convincing websites.

“It really has reached an incredible level of creative activity, an incredible level of graphic design, and so much so that these are almost identical versions of the associated websites,” said O’Brien, who added that the original e-mails also are becoming increasingly clever at luring phish into giving away their account numbers and passwords.

The RBC e-mail, for example, warned recipients that RBC had updated its servers because, well, bad people had been sending out e-mails that tried to draw customers to fake sites.

Also recently, an e-mail was circulating carrying the return address of the Quebec-based financial powerhouse Desjardins, attempting to draw unwary Visa card holders to another phishing site.

Despite all the warnings and the publicity saying that banks and other financial institutions never, ever, send out e-mail requests for information, people continue to visit and hand over their account numbers and passwords.

But, said O’Brien, it’s no wonder people get fooled these days.

“I almost got fooled myself recently.”

He had opened a new bank account for his son, who was headed off to college.

A couple of days later O’Brien got an e-mail from the bank telling him there was a problem with the online account.

“My antenna went up because I’m naturally skeptical. But I thought, well, it’s possible because I did just open an account and if there were a need to contact me, I had provided them with my e-mail address.”

There were no misspellings in the e-mail. The graphics were impeccable. And the message made it through O’Brien’s e-mail filters.

But O’Brien did the right thing and called the bank, and found out it was a fake.

“And I thought I had reached a certain level of not being able to be surprised any more.”

RBC manager of media relations Jackie Braden said that she couldn’t comment as to whether phishers were becoming increasingly clever.

“But what I can say is that whenever people do get an e-mail like this, they should know that it’s not coming from a bank,” said Braden. “We never ask for client information, personal identification or account information in an e-mail.

“If a client gets one like that, they should close it and delete it right away.”

One good reason for ditching the e-mail immediately, said O’Brien, is that it could also contain a trojan that would allow the senders to acquire your passwords by other means.

“It’s possible for a trojan to be downloaded on to your PC, and the next time you attempt to log on to your bank it would bring up a fictitious website and you would subsequently provide a third party with your log-in information without even knowing that would happen,” said O’Brien.

Braden said RBC has a number of safeguards built into its site — such as allowing users to set up a series of questions they have to answer before gaining access.

And, since April, HSBC Bank Canada has instituted a method that puts a number of major barriers in the way of phishers trying to get information.

At its online banking site, HSBC has users choose between five different questions that have to be answered each time they sign in, such as what was your first car?

“You come up with a memorable answer to that, which only you know,” said Shelley Maher, HSBC Canada vice-president, direct channels. “It would be very difficult for a phishing site to match the exact question you’ve asked.”

After that, users have to fill in three random characters, numbers and letters of their passwords, again making it difficult for phishers to gather complete password information.

In another move, the developers at Mozilla will be including phishing protection in their upcoming Firefox 2.0 browser that will — working from a constantly updated list of known phishing sites — warn users that they could be about to give away their financial information.

And, recently, techies at E-gold struck back at phishers — who link to images on the real E-gold site — by replacing the original images with ones that warned users that they were on a scam site.

O’Brien said he applauds all these moves, and especially encourages banks to issue constant warnings to customers that they will never send out information-gathering e-mails, but it’s a constant battle to stay ahead of the bad guys.

“The level of complexity [of phishing attacks and sites] is increasingly amazing,” said O’Brien. “And one of the things that it has done is that even those institutions and enterprises that feel as though they have their security solution settled are beginning to realize that there’s no end to it.

“Complacency in this instance will lead to danger, it’s not something that can be taken for granted.”

O’Brien added that the more obstacles that the security industry tries to put in front of virus writers and hackers the more creative they have to be in order to overcome those obstacles.

“And certainly there is a certain level of naivete required to fall victim. But, as I said, I came perilously close myself.

“And I’m sure if the e-mail had been addressed to my son or anyone else in my family I’m sure they would have clicked on the link.”

© The Vancouver Sun 2006