City police target the worst property offenders for face-to-face interviews

Chad Skelton

Sun

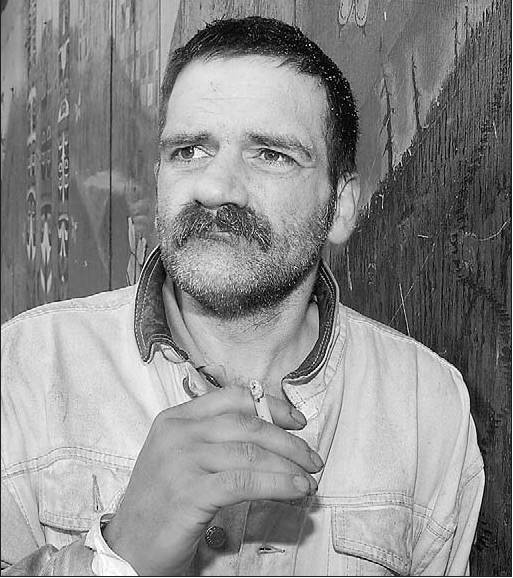

GLENN BAGLO/VANCOUVER SUN FILES Clinton Dreyer is a crack addict and petty thief with a sheet of 80 criminal convictions. He lives at the Portland Hotel when he’s not doing time for his crimes.

In a small, windowless interview room at the Vancouver lockup, a police officer and a suspect sit down for a chat. On one side of the table is Clinton Dreyer, a crack addict and petty thief with 80 criminal convictions, who was picked up the night before for shoplifting.

On the other is Det.-Const. Rowan Pitt-Payne, a longtime investigator with the Vancouver police.

“I’m not here to talk about what you’re in here for,” Pitt-Payne tells Dreyer. “I’m here to talk about how we can stop you from coming back.”

MIND-BOGGLING IN SCOPE

Greater Vancouver has one of the worst property crime rates in North America — fuelled in large part by drug addicts hungry for their next fix. Last year alone, this region’s thieves broke into more than 25,000 homes and businesses and 40,000 cars — stealing millions of dollars worth of stereos, CDs and jewelry.

Lower Mainland residents are more likely to have their cars broken into than residents of any other major Canadian city — four times more likely than those in Toronto.

It is a problem so mind-boggling in scope that police forces have become desperate for solutions.

In Vancouver, one of the things police are trying is the chronic-offender program.

Criminologists have long known that a majority of property crime is committed by only a small number of criminals — chronic offenders who break into cars or homes virtually every day.

For the past 18 months, four Vancouver police detectives and one civilian have been assigned to identify and crack down on the city’s worst property offenders.

And while that mission involves a lot of traditional police work — like surveillance and arrests — it also has, at its heart, a notion almost radical in its simplicity.

“We’re getting to understand our offenders face-to-face,” said Pitt-Payne, one of the detectives with the unit. “What we’re interested in doing is identifying what makes this person tick — what is making this person a criminal? And trying to deal with the roots [of the problem] rather than keep on arresting him over and over again.”

Which is how Pitt-Payne came to be talking to Dreyer one morning last February. (Pitt-Payne invited this reporter to sit in on that interview and Dreyer agreed.)

As the interview began, Pitt-Payne asked Dreyer about his education (he finished Grade 10) and his mental health (he suffers from paranoid schizophrenia and often forgets to take his medication).

“What kind of drugs do you use?” asked Pitt-Payne.

“Coke.”

“You smoke it?”

“Yeah.”

“You inject at all?”

“No, I quit a couple of years ago.”

Dreyer, who lives in the Portland Hotel in the Downtown Eastside, told Pitt-Payne he knows the impact his drug addiction is having on himself and others.

“I like to smoke it. I like being high,” he said. “But I don’t know if it’s worth it because you end up stealing again and pissing people off. I’d like to be clean.”

Pitt-Payne asked how much he’s usually paid for the things he steals.

“Maybe 10 per cent of the [true value],” said Dreyer. “At first, some guys give you half price or a third. You’re supposed to get a third. But you don’t. Because they know you want the coke.”

And how much does he spend on cocaine each day?

“My drugs end up costing me about $500 a day,” he said.

Pitt-Payne, thinking out loud, said that means Dreyer has to steal about $5,000 worth of goods every single day to feed his habit.

Dreyer admitted he does several thefts a day. His specialty, he said, is stealing liquor from restaurants or paintings off the walls of hotels. “It’s good, valuable artwork,” he said. “It’s more respectful than breaking into some old lady’s house.”

Finding someone to buy the stuff he steals is easy, he said.

Usually all he has to do is walk into one of the Downtown Eastside’s seedy bars and someone will call him over to haggle.

Christmas is the busiest time in the bars, he said, when people come down from the suburbs to shop for deals.

In some cases, he said, he can barter directly with the drug dealers.

Pitt-Payne asked Dreyer what it would take for him to stop committing crimes.

“I’d have to control my cocaine habit,” he said.

And is he willing to quit drugs?

“I’m willing to try,” said Dreyer. “But it’s not going to happen in this neighbourhood.”

Pitt-Payne reached his last question, the one he asks every chronic offender.

“What can I do to help you?” he asked.

“Get me bail,” says Dreyer, chuckling.

But Dreyer is probably out of luck.

Pitt-Payne said officers in his program do everything they can to get “their guys” into drug treatment or mental health programs — in the hopes such assistance will stop, or even slow down, their criminal activity.

Starting this past week, a social worker with Vancouver Coastal Health was assigned on a temporary basis to the program to help place such offenders in treatment and housing.

But the other main goal of the program is to get Vancouver’s chronic offenders put behind bars for as long as possible.

The reason, said Pitt-Payne, is that offenders in the program are so prolific that getting them off the streets for even a few weeks can have a significant impact on crime.

He said officers also believe a lengthy prison stay may be the only way for some of these people to turn their lives around.

“These guys do remarkably well in a structured environment,” said Pitt-Payne. “When you see them in prison, they’re totally different.”

It’s also often easier for offenders to get clean and access drug treatment in jail than on the streets, said Pitt-Payne.

“The longer the sentence, the better your chances of accessing programs,” he said. “The happy endings we see are in prolonged incarceration.”

Dreyer himself illustrates the point.

When Pitt-Payne interviewed him on Feb. 16, Dreyer was in bad shape

His hands were filthy, as if he had been binning for bottles and cans, and he wore a tattered blue sweater and stained blue jeans.

He looked incredibly tired, struggling to keep his eyes open as he answered Pitt-Payne’s questions.

The next day, Dreyer was sentenced to 20 days in jail and sent to the Fraser Regional Correctional Centre in Maple Ridge.

On March 9, shortly after Dreyer was released, The Sun caught up with him again at his room at the Portland Hotel.

He was clearly still struggling — his shoes were soaked through and his clothes were dirty — but he looked healthier than he had a month earlier and said his time in jail had been good for him.

“I got my sanity,” he said.

MAKING THE CASE

To try to keep people like Dreyer in jail, the chronic-offender program keeps detailed files on all its targeted offenders — about 70 at the moment.

When one of them comes before the courts, either for bail or sentencing, detectives write up a brief report on the offender and e-mail it to the Crown attorney’s office.

That report includes the offender’s criminal record, but also information gleaned from interviews like the one with Dreyer — such as the nature of his drug addiction.

Stan Lowe, spokesman for B.C.’s criminal justice branch, says prosecutors find the reports useful in making their arguments to judges.

One of the main legal grounds to deny people bail is that they are likely to commit another crime if they are released.

Knowing that someone has a $500-a-day drug habit — and no visible means of support — makes it a lot easier to make that case.

“Unless there’s an immediate plan for rehabilitation or treatment in the works, it assists the Crown in being able to point out that this is a significant risk factor,” said Lowe.

When the chronic-offender program began, one of the first tasks was to make a list of all such offenders in Vancouver.

The typical definition that criminologists use is someone who has been charged five times in the past year — on the assumption that if you’ve been caught five times, you’re committing dozens more offences.

But as the unit started making such a list, it soon ran into a big problem: there were just too many people that fit that description.

“It was ballooning,” said Pitt-Payne.

When they got to 800 offenders, they stopped counting.

WORST OFFENDERS BEHIND BARS

Eventually, just to keep things manageable, the unit had to limit itself to about 70 offenders with 12 or more charges in the past year — a category one criminologist dubbed “super-chronic offenders.”

Pitt-Payne said that when he talks to police officers in other cities, they can’t believe such criminals even exist.

“Other police forces get slack-jawed when they hear how many chances you get in Vancouver,” he said.

“They laugh at us — ‘What is somebody with that number of charges still doing on the street?’ “

No detailed study of Vancouver’s chronic- offender program has been conducted yet. But there are some hopeful signs it is beginning to make a difference.

As of February, there were 72 people with 12 or more charges on the unit’s list. As of this week, that’s down to nine.

Pitt-Payne said the reason is simple: many of the worst offenders are now behind bars.

“We’ve been running long enough [now] that we’ve incapacitated and disrupted some of them,” he said.

That’s allowed the team to move onto the next tier of offenders — those with five to 10 offences over the past year — and to take more “special requests” from senior officers to target criminals who don’t have enough charges to make the grade but are still considered a problem.

Included in the list of chronic offenders now behind bars is Dreyer.

Since The Sun spoke with Dreyer in early March, he’s been picked up for theft four more times — most recently on Aug. 6. Dreyer pleaded guilty to that charge and was sentenced on Aug. 21.

This time, the Crown had a fresh report from the chronic-offenders program. The judge gave him 90 days.

That’s 90 days that Dreyer won’t be stealing, Pitt-Payne said. “For a Vancouver court, that’s a big sentence.