Randy Shore

Sun

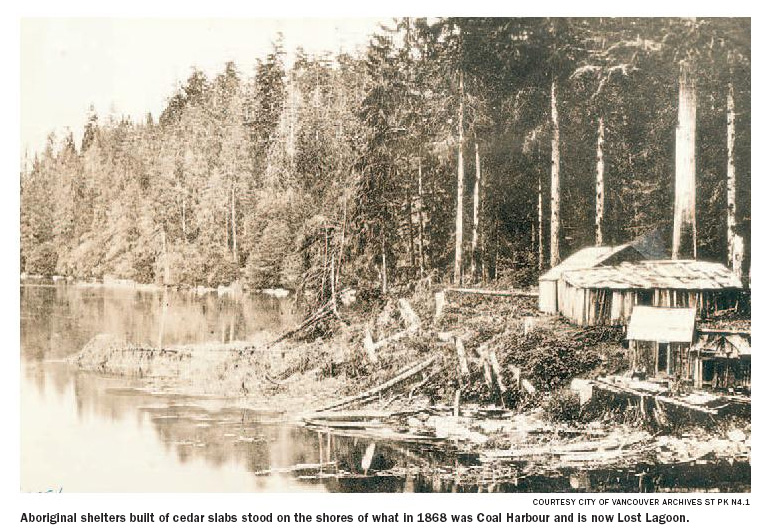

Millennia-old native village sites in Stanley Park were still in use by first nations people in the 1880s when surveyors and road builders knocked the homes down to create the Park Drive perimeter road.

Road workers chopped away part of an occupied native house that was impeding the surveyors at the village of Chaythoos (pronounced “chay toos”), near Prospect Point. City of Vancouver historian J.S. Matthews interviewed August Jack Khatsahlano, who was a child in the house at the time.

“We was inside this house when the surveyors come along and they chop the corner of our house when we was eating inside,” Khatsahlano said in that 1934 conversation at city hall.

“We all get up and go outside see what was the matter. My sister Louise, she was only one talk a little English; she goes out ask Whiteman what’s he doing that for. The man say, ‘We’re surveying the road.’

“My sister ask him, “‘Whose road?'”

Most of the native inhabitants at Chaythoos left the park at that time and went to live on the reserve at Kitsilano Point, which was later transferred by the province to the federal government and eventually sold.

“When they left they took the above-ground grave of their chief with them when they left,” according to historian Jean Barman. The remains of Chief Supplejack, father of August Jack, had been kept in a cedar mausoleum at Chaythoos, the bones stored in canoe-shaped sarcophagus.

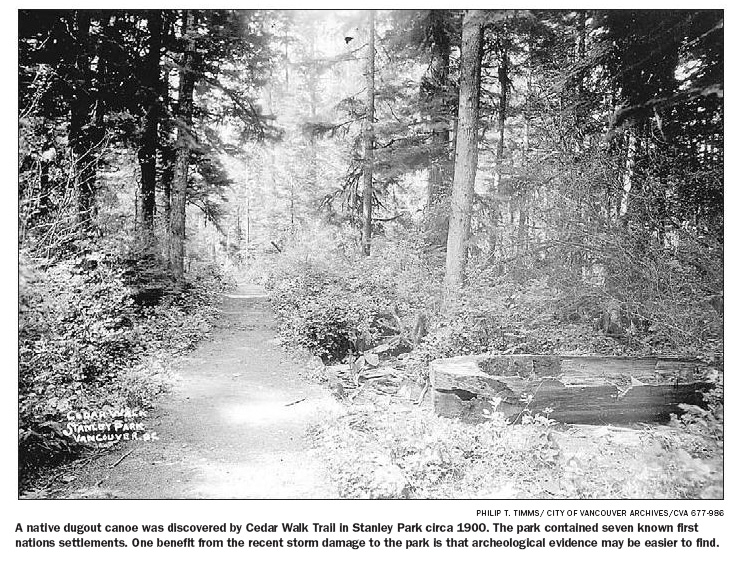

The last archeological survey of the park, completed in 1995 by Sheila Minni and Michael Forsman for the Ministry of Highways, found four new archeological sites. Their report also expanded the known boundaries of five of the seven previously known sites in the park.

Their survey was limited to the eastern half of the park and concentrated on areas affected by the expansion of the Stanley Park and Lions Gate causeway. The authors note that no complete survey of archeological and heritage resources in the park has ever been done.

Further investigation, they say, would likely reveal even more sites and contribute to the picture of native life and historic use of the park by native peoples.

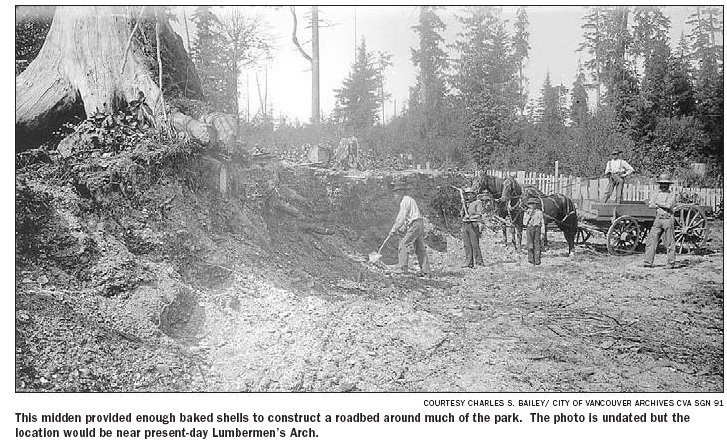

Of one lost site, August Jack told Matthews of a burial ground not far from Xwayxway — now the site of Lumbermen’s Arch — that dates to “long before” his time. Its location remains unknown, though a letter to Matthews from local anthropologist Charles Hill-Tout notes that several skeletons were found during a road crew excavation of the shell midden at Xwayxway.

The largest settlement in the park in the 1880s, during August Jack’s time, was at Xwayxway, which was razed when the road went through.

The big house of that settlement was more than 60 metres long and about 20 metres wide, according to the interview with Khatsahlano. The building was constructed from large cedar posts and slabs. More than 100 people in 11 families lived there.

A potlatch was held at Xwayxway (pronounced “whoi whoi”) in 1875 in that longhouse, according to the commemorative integrity statement published when the park was declared a national historic site. The potlatch, held in the chief’s longhouse “Tay-Hay,” is also mentioned in the minutes of a city council meeting in which the medical health officer recommends destruction of the buildings at Xwayxway because of a smallpox outbreak, according to Eric McLay, president of the Archaeology Society of B.C.

Much of the native history of the park is shrouded in the mists of time. But Capt. George Vancouver encountered and wrote about people of the Squamish nation on those lands when he explored the area in 1792.

Spanish explorer Jose Maria Narvaez conducted a cursory exploration of the peninsula and the Burrard Inlet in 1791. But it was Vancouver who wrote about the area and its people at length in his journals.

Vancouver records it as an island, as the area from Coal Harbour west was submerged at high tide. He was met by 50 natives in canoes “who conducted themselves with the greatest decorum and civility,” he wrote in his journal.

The “Indians” presented Vancouver and his men “with several fish cooked, and undressed, of the sort already mentioned as resembling the smelt.”

He continued: “These good people, finding we were inclined to make some return for their hospitality, shewed much understanding in preferring iron to copper.”

Barman, an expert on the native history of the park, said the size and depth of the midden heaps found in the park suggests native settlement goes back much further than the good captain’s visit.

The midden at Xwayxway was so large that road crews who mined the site for calcined (fire-heated) shell used the distinctive white material to pave Park Drive “from Coal Harbour around Brockton Point and a long distance towards Prospect Point,” according to the notation on a City of Vancouver Archives photo of the crew excavating the midden heap.

Documents supporting the National Historic Site designation bestowed on the park by the federal government in 1988 note the existence of burial sites, middens and “long-abandoned villages” as well as acknowledging two “named” Squamish villages, Xwayxway and Chaythoos.

Minni and Forsman’s report includes five other native place names: Slhxi’7elsh (Siwash Rock), Ch’elxwa7elch (Lost Lagoon/Coal Harbour), Oxachu (Beaver Lake) and Papiyek (Brockton Point) and Skwtsa7s (possibly Deadman’s Island).

The documents suggest that the native settlements within the park boundaries are at least 3,000 years old.

“There’s evidence that [first nations people] were there for a very long time,” said Barman. “And this part of the history of Stanley Park has been acknowledged very little.”

“They talk about it as a sort of mythic past as opposed to saying that they were there when Europeans arrived and visibly living there until the 1920s,” said Barman, author of Stanley Park’s Secret: The Forgotten Families of Whoi Whoi, Kanaka Ranch and Brockton Point.

Midden heaps are scattered throughout the park, some of them close to the major trails that criss-cross the park today, Barman said. Their existence suggests that other village sites are likely waiting to be found, she said.

“There’s more there than just the midden heaps,” Barman said.

The site of Chaythoos village is noted on a brass plaque placed on the low lands east of Prospect Point commemorating the centennial of the park in 1988.

The apocryphal story has Lord Stanley spreading his arms and dedicating the park “to the use and enjoyment of peoples of all colours, creeds, and customs, for all time.” In fact, he would not visit the park until the following year, as governor-general.

“They so much wanted to erase the fact of the aboriginal presence in the park that they held the park opening ceremonies on the site of Chaythoos after they chased out the people who lived there,” Barman said.

The restoration of the park’s storm-damaged areas is a perfect opportunity to do some archeological prospecting and get a better idea of the potential richness of these troves, Barman said.

Stanley Park restoration task group leader Jim Lowden said the archeological survey being used by the park board shows the general location of a handful of significant sites around the park. The report, Status of Archaeological Sites on Lands Administered by the City of Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation, was prepared for the provincial government in 1978.

The text makes reference to shell middens, with no detail about the other possible contents of ancient settlement sites, Lowden said.

McLay said only a fraction of the park has been properly surveyed and suspects many hidden features may have been damaged by winter storms.

Minni and Forsman recorded 92 culturally modified trees (CMTs), mainly in the area east of Pipeline Road.

“There is a high potential that undiscovered CMTs and other smaller heritage sites may be located in these areas of wind damage — just because no one has looked, doesn’t mean they don’t exist,” McLay said.

The restoration of the park is a great opportunity to add to our knowledge of the first nations history of the area and to make those sites part of the public park experience for visitors, he said.

While the Squamish Nation has the most recent history in the park, the downtown peninsula and much of the area of Vancouver is subject to at least five competing land claims, including assertions of historical use by the Sto:Lo, Musqueam, Tsleil Waututh and the Hul Qumi Num treaty group.

The Lower Fraser River region and Puget Sound were the centre of a thriving Coast Salish culture prior to European settlement, according to Bruce Miller, an anthropology professor at the University of B.C.

Stanley Park is part of the core Coast Salish territory, which includes the east coast of Vancouver Island, the Fraser River to Yale and in Puget Sound. It was one of the largest, most densely populated nations in aboriginal North America and unique because it did not depend on agriculture.

“These are people who travel by canoe, they are water travellers and this territory is part of a complex of waterways connecting places,” Miller explained. The Coast Salish did not define ownership of places in the modern sense, although they have assimilated European notions of land ownership, which tends to muddy land claims.

“Any one longhouse group would have a winter house in one place and procurement stations in other areas,” he said. Settlements, areas of stewardship and foraging areas were controlled by family groups and access was regulated through a complex network of kinship associations often built through marriage between clans.

“If you didn’t have direct stewardship of a place and you didn’t have access through kinship you just weren’t going there,” Miller said. “The key word is protocol; you could get access to these places but you have to do the right things, talk to the right guy and ask permission in the right way.”

Over the centuries before European contact, many family groups could have made use of the sheltered sites and food-gathering areas in and around Stanley Park. Out-marrying was constantly expanding the kinship networks, Miller said.

Tsleil Waututh (Burrard Band) spokesman Leonard George said his people’s history in the Burrard Inlet is one of continuous occupation and use dating back thousands of years.

But political and kinship affiliations allowed people from other clans to use prime harvesting and fishing areas at different times of the year and many of those relationships are still in evidence today.

“Even in the last five generations, we have relationships through our grandmothers to the Squamish people,” George said.

“My first cousins now are Squamish,” he said.

The first nations understanding of ownership allowed those lands “to be shared in peace.”

“We spent as much time in Squamish or at Musqueam as they did here,” George explained. “That’s even during my lifetime. We would forage feast where the clam picking was good and conduct our ceremonies together.”

“We respect common areas like Stanley Park collectively,” George said.

George said his family traces the George surname to the arrival of Captain George Vancouver, one of the first Europeans who had significant contact with native people in Stanley Park and Burrard Inlet.

First nations people will be working with the park board on every aspect of the park’s storm damage cleanup, restoration and future development.

“We want to make sure that our middens and anthropological interests are cared for,” George said. “Then maybe build a longhouse village to commemorate all of our history there.”

If something good can be said to come of the massive damage that winds and snow storms wreaked on the park this winter, it is that first nations and park officials are finally talking in a constructive way about first nations history in Stanley Park, he said.

STANLEY PARK WAS AN ‘ISLAND’ WHEN VANCOUVER SAW IT

Capt. George Vancouver’s description of his first dealings with the aboriginal people living in today’s Stanley Park:

From Point Grey we proceeded first up the eastern branch of the sound, where, about a league within its entrance, we passed to the northward of an island [Stanley Park] which nearly terminated its extent, forming a passage from ten to seven fathoms deep, not more than a cable’s length in width. This island lying exactly across the channel, appeared to form a similar passage to the south of it, with a smaller island lying before it. From these islands, the channel, in width about half a mile, continued its direction about east. Here we were met by about fifty Indians, in their canoes, who conducted themselves with the greatest decorum and civility, presenting us with several fish cooked, and undressed, of the sort already mentioned as resembling the smelt. These good people, finding we were inclined to make some return for their hospitality, shewed much understanding in preferring iron to copper.

For the sake of the company of our new friends, we stood on under an easy sail, which encouraged them to attend us some little distance up the arm. The major part of the canoes twice paddled forward, assembled before us, and each time a conference was held. Our visit and appearance were most likely the objects of their consultation, as our motions on these occasions seemed to engage the whole of their attention. The subject matter, which remained a profound secret to us, did not appear of an unfriendly nature to us, as they soon returned, and, if possible, expressed additional cordiality and respect. This sort of conduct always creates a degree of suspicion, and should ever be regarded with a watchful eye. In our short intercourse with the people of this country, we have generally found these consultations take place, whether their numbers were great or small; and though I have ever considered it prudent to be cautiously attentive on such occasions, they ought by no means to be considered as indicating at all times a positive intention of concerting hostile measures; having witnessed many of these conferences, without our experiencing afterwards any alteration in their friendly disposition. This was now the case with our numerous attendants, who gradually dispersed as we advanced from the station where we had first met them, and three or four canoes only accompanied us up a navigation which, in some places, does not exceed an hundred and fifty yards in width.

We landed for the right about half a league from the head of the inlet, and about three leagues from its entrance. Our Indian visitors remained with us until by signs we gave them to understand we were going to rest, and after receiving some acceptable articles, they retired, and by means of the same language, promised an abundant supply of fish the next day; our seine having been tried in their presence with very little success. A great desire was manifested by these people to imitate our actions, especially in the firing of a musket, which one of them performed, though with much fear and trembling. They minutely attended to all our transactions, and examined the color of our skins with infinite curiosity. In other respects they differed little from the generality of the natives we had seen. They possessed no European commodities, or trinkets, excepting some rude ornaments apparently made from sheet copper; this circumstance, and the general tenor of their behavior, gave us reason to conclude that we were the first people from a civilized country they had yet seen. Nor did it appear that they were nearly connected, or had much intercourse with other Indians, who traded with the European or American adventurers.

Perfectly satisfied with our researches in this branch of the sound, at four in the morning of Thursday the 14th [Date: 1792-06-14], we retraced our passage in; leaving on the northern shore, a small opening extending to the northward.

As we passed the situation from whence the Indians had first visited us the preceding day, which is a small border of low marshy land on the northern shore, intersected by several creeks of fresh water, we were in expectation of their company, but were disappointed, owing to our travelling so soon in the morning. Most of their canoes were hauled up into the creeks, and two or three only of the natives were seen straggling about on the beach. None of their habitations could be discovered, whence we concluded that their village was within the forest. Two canoes came off as we passed the island, but our boats being under sail with a fresh favorable breeze, I was not inclined to halt, and they almost immediately returned.

The shores of this channel, which after Sir Harry Burrard of the navy, I have distinguished by the name of BURRARD’S CHANNEL.

— from the journal of George Vancouver titled “Quit Admiralty Inlet, and proceed to the Northward — Anchor in Birch Bay — Prosecute the Survey in the Boats — Meet two Spanish Vessels — Astronomical and Nautical Observations” dated June 13, 14, 1792.

© The Vancouver Sun 2007