Byron Acohido and Jon Swartz

USA Today

David Hernandez has spent 1½ years dealing with credit bureaus and creditors. To prove he was overseas when fraudulent accounts were opened, he used his military orders. Plus, he has put fraud alerts on his credit records.

After graduating from high school, David Joe Hernandez served four years in the Air Force at bases in New Mexico and Japan. So it came as a shock when he returned home to Oak Forrest, Ill., and discovered collections agents were hunting him down to make good on some 20 delinquent accounts.

That was in November 2004. Hernandez spent hours trying to clear up the mistakes through Experian, Equifax and TransUnion, the Big Three credit-reporting agencies. But things got worse. He learned he was linked to a string of felonies, including a drug charge that hindered him from landing a job at Best Buy. Then last August, state regulators began garnishing his wages to pay child support to a woman in Chicago he’d never heard of.

“I was astonished,” Hernandez says. “One thing after another kept turning up, and it couldn’t have been me because I wasn’t even in the area.”

Hernandez was the victim of new-account fraud — the most difficult type of identity theft to detect, resolve and prosecute. For decades, thieves have used stolen Social Security numbers to open new financial accounts that piggyback on a victim’s good credit, piling up outstanding balances and damaging credit ratings. In the digital age, criminals buy and sell stolen Social Security numbers — the key ingredient for new-account fraud — on the Internet. Crooks use them to apply online for credit cards, auto financing and mortgages. The credit-reporting agencies make approval of such loans a snap.

The result is a marked rise in new-account fraud, say credit industry and tech security experts. Tens of millions of Social Security numbers have been reported lost or stolen in the past two years. Edentify, a Bethlehem, Pa.-based database security firm, has analyzed some 500 million names paired with Social Security numbers and found 5 million numbers being used fraudulently.

Edentify CEO Terrence DeFranco says new-account fraud will continue escalating.

“I see the targets increasing,” he says. “We will see it at all levels of society.”

Three Davids

What happened to David Hernandez shows how crooks seize opportunities created by a centralized credit-issuing system.

Experian, Equifax and TransUnion use data-mining technology to assemble loan and payment histories and issue quick credit reports. “The goal is to try to deliver as many credit reports to lenders as possible,” says John Ulzheimer, president of Credit.com Educational Services, which advises consumers on credit management. Ulzheimer is also a former manager at Equifax and Fair Isaac, a pioneer in developing credit-scoring systems.

A 2005 survey by the U.S. Public Interest Research Group found 79% of credit reports contained errors, and 25% contained enough mistakes to prevent the individual from obtaining credit. Once the credit system accepts bad data, it can be next to impossible to clear.

But the credit bureaus say mistakes are rare. “Credit has been democratized,” says Stuart Pratt, president of Washington D.C.-based Consumer Data Industry Association (CDIA), which lobbies for the credit bureaus. Automated credit reports have “facilitated economic growth in this country, and saved consumers money,” Pratt says.

While he lived a low-key military life, Hernandez’s identity was hit by a double whammy. A crook in Chicago used his Social Security number to create and siphon new accounts, says Rick Lunstrum, vice president at ID Watchdog, a Denver-based identity-theft detection and resolution firm Hernandez retained to help him.

Complicating matters, separately, Hernandez’s personal records became entangled with those of a convicted felon in Mesa, Ariz. — not the thief racking up new accounts in the Chicago area.

Hernandez first became aware of the problems after he was discharged from the military and returned from a 16-month tour of duty at Misawa Air Base in Japan. First National Bank of Chicago called him seeking payment of a delinquent $4,500 loan.

He ultimately learned that the Big Three credit bureaus listed him as responsible for 20 delinquent accounts for cellphone bills, credit cards, utility bills and hospital bills. “All of the billing addresses were to places in Chicago — places I’d never lived,” he says.

It’s impossible to know how the thief in Chicago obtained Hernandez’s number. In the old days, someone would have sneaked a peek at his military, tax or driving records, written down his personal information, then used it to open accounts or sold it to another thief in a person-to-person exchange.

Today, Social Security numbers in digital form are turning up missing by the tens of millions. Insider thieves and hackers crack into company databases; Internet crime gangs infect Web pages with tiny programs that capture data typed into online banking and shopping pages, and send out waves of e-mail spam that trick consumers into giving up sensitive information.

“We exhausted all types of avenues in regard to finding out how David’s Social Security number became available in Chicago all the way from Japan,” Lunstrum says. “Based on current trends we’re seeing in identity theft, it was likely done online.”

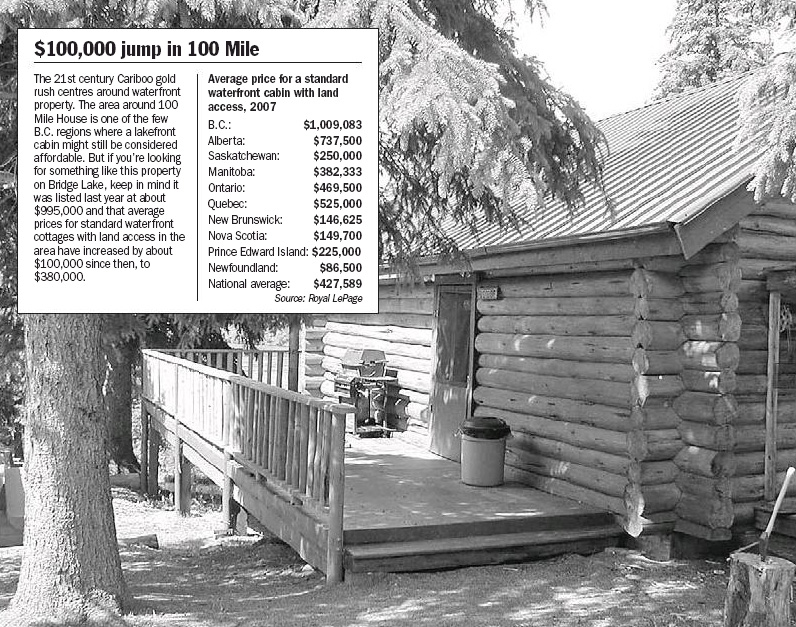

Hernandez spent much of his free time for the next year and a half on the phone or corresponding with the credit bureaus and creditors.

To prove that he was out of the country when the accounts were opened, he compiled a packet of his military orders.

He learned that he was associated with an arrest warrant in Arizona for driving on a revoked license and that a David Hernandez had a record there for auto theft, evading law enforcement, making wrongful statements to law enforcement, wrongful use of a weapon and driving on the wrong side of the road.

Then last July, a week after Hernandez started working at Best Buy, his manager informed him he was being let go because a criminal record check came back showing a felony drug conviction.

Hernandez had joined the Air Force months after graduating from high school and rose to staff sergeant and jet fighter crew chief. “I’ve never been in trouble with the police,” he says.

Hernandez was reinstated at Best Buy after appearing before a judge to get a new driver’s license and expunge the criminal records. “I had to go to court to prove I wasn’t in the States during the time of these incidents,” he says.

Built for speed

Credit bureaus Equifax, Experian and TransUnion track histories of loans and payments. Together with data brokers such as LexisNexis, ChoicePoint and Acxiom they supply information to lenders, landlords, insurance companies, employers and law enforcement. The data brokers collect information from real estate and motor vehicle records, along with other public records to produce information dossiers on individuals.

ID Watchdog purchased Hernandez’s file from LexisNexis. It included criminal records for David Hernandez from Mesa.

David Hernandez from Oak Forrest and David Hernandez from Mesa were born on the same day in 1981, but their Social Security numbers are different, Lunstrum says. And the Mesa David had nothing to do with the delinquent accounts created by the Chicago David, he says.

Data brokers and credit bureaus are “in the business of selling information,” Lunstrum says. Inaccurate and commingled data often accumulate in individual files. “If they start putting filters on, then maybe they won’t have as much output to sell,” he says.

Data brokers say their information accurately reflects the contents of public records. When records for two individuals get mixed, “It’s up to law enforcement to decide if there’s a connection or not,” says Sue D’Agostino, of LexisNexis.

The credit bureaus do not disclose details about how they verify identities of loan applicants and decide which records to pull into a credit report. TransUnion spokesman Steve Katz cites the danger of divulging “an unintentional instruction manual” for crooks.

But criminals have devised countless scams that take advantage of the system. A thief filling out an online loan application can submit fewer than nine correct digits of a Social Security number and just three matching letters of the first name of someone of good credit standing. Often that’s enough to deliver a credit report and approval for a credit card, says David Szwak, a Shreveport, La.-based attorney who represents consumers in Fair Credit Reporting Act lawsuits.

“The three letters of the first name don’t even have to be in the same order or sequence. Marsha and Mark would be the same person; David and Diana would be the same,” Szwak says.

The bureaus also ignore the applicant’s date of birth and work history; this makes it easy for thieves to create new accounts by submitting a slightly tweaked name and Social Security number — or even use a dead person’s or juvenile’s personal data, Szwak and other credit industry experts say.

The Chicago David happened to share the full name of Oak Forrest David. But the thief did take advantage of another credit bureau practice: accepting any address submitted by a loan applicant as the current address. He thus diverted credit cards and billing statements into his hands, Lunstrum says.

Mike Baxter, a Portland, Ore.-based plaintiffs’ attorney, says consumers requesting their own credit reports often do not get to see derogatory data attached by mistake or instigated by a scam artist. “Yet that data would appear on the credit report the bank or mortgage company orders, which is a huge problem,” Baxter says.

Former credit bureau manager Ulzheimer says the bureaus supply consumers with a report that includes only loan and payment records with a perfect match of name, address, Social Security number and birth date.

While declining to discuss details of how credit reports are pulled, the CDIA’s Pratt insists everyone is treated equally.

In today’s digital world, anyone whose Social Security number has been lost or stolen remains at ongoing risk, indefinitely. Ulzheimer and other consumer advocates say there is little stopping crooks from using a number over and over.

Take Hernandez. Last summer, after Best Buy reinstated him, he received notice that Illinois was garnishing 60% of his reservist’s pay. The reason: to pay child support to a woman he’d never met who was using an address that had been on several fraudulent accounts. It took him several weeks and two in-person interviews with state family services regulators to remove the garnishment.

Earlier this year, ID Watchdog says, someone tried three times to take out auto loans using Hernandez’s name and Social Security number. But Hernandez had placed fraud alerts on his credit records, so the loans were denied.

Hernandez believes the continued attempts to use his name have hurt his credit rating. “I’ve done everything I could to keep up good credit, but no matter what I do, I come up losing,” he says.