Miro Cernetig

Sun

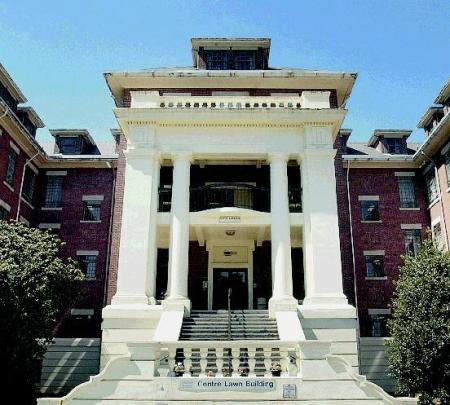

Centre Lawn Building at Riverview, B.C.’s old psychiatric hospital that may be transformed into a massive real estate development. Photograph by : Bill Keay, Vancouver Sun, files

VICTORIA — The site of B.C.’s century-old psychiatric hospital may soon be transformed into a massive real estate development that will mix the affluent, the poor, the mentally ill and the disabled, the minister responsible for housing said Thursday.

Rich Coleman said the redevelopment of the old Riverview facility, situated on 98 hectares in Coquitlam, would include market housing, social housing and housing for the mentally ill and disabled, including beds for those who need institutional care.

While firm numbers for the size of the development have not been established, Coleman said he didn’t think early staff proposals for up to 7,000 units were nearly high enough.

Coleman said he didn’t know when the first units of the new project would be available, if it goes ahead, but said the project wouldn’t be completed until after the Olympics.

Coquitlam will have a say on what happens to the site, Coleman said, adding nothing will be shoved down the municipality’s throat. And he suggested Vancouver Mayor Sam Sullivan, who has suggested more immediate use should be made of Riverview, should butt out of the issue.

Once staff comes back with new plans, they will go to cabinet, which will agree on models for the proposed development by August or September.

This fall, the proposed models will go to public meetings in Coquitlam for input from residents there.

The redevelopment, which would be one of the biggest real estate deals in recent memory, is the B.C. government’s 21st-century vision for Riverview, a controversial institution that Vancouver-historian Chuck Davis describes as having “started up about a century ago as the Hospital for the Mind … operating out of a hay barn on 1,000 acres.”

Coleman, a former real estate developer who oversees the provincial social housing file, told The Vancouver Sun Thursday he sees the institutions grounds as a new community that could be built as a P-3 — the public, private partnerships model the Liberal government has embraced.

That P-3 model would attract private developers to raise capital to build and pay the government for social housing and beds, he said. In exchange, they would be given the right to sell thousands of newly built condos and homes at market rates on one of the Lower Mainlands last great swaths of undeveloped land.

Coleman says it will have to meet local zoning laws, pass public approval and preserve the bucolic green spaces that are one of Riverviews features.

But Colemans plans are big.

So far, early suggestions from government staff are that anywhere from 4,500 or 7,000 units be built at Riverviews expansive compound. Coleman would not say how many of those would be for the mentally ill or social housing, but said from the Ministry of Health, “Ive heard around 1,100 units is what they felt was the number they were thinking they needed integrated into the site.”

But Coleman thinks his staff may be thinking far, too small given the land in question.

The minister sent them back to the drawing board, asking for more housing units on the site, adding that at a similar government site being redeveloped in Vancouver Little Mountain, which sits on six hectares (15 acres), is expected to create 2,000 units, many of them social housing.

“The reality is I dont think either one of those [Riverview] proposals is actually comprehensive enough to take to the public,” said Coleman in an interview.

“Six, seven thousand units on 244 acres in an urban centre really isnt very many. So the question had to be , Are you prepared to take a look at real densities, where you protect green space and at the same time go up…?”

While Coleman stresses Coquitlam residents, and its city council, will ultimately decide what happens, hes thinking condos and towers may be the taxpayers best bet for utilization of the land.

“What wed like to do is have a comprehensive plan here where the amount of density that is on the site actually pays for the health care component so the taxpayer doesnt have to come up with additional capital.”

It is unclear how the residents and political leaders will react to the idea.

But Coleman has said he believes the community, which has long housed Riverview, is ready for the debate.

Coquitlam Mayor Maxine Wilson said shes had general discussions with the provincial government on the use of Riverview, including a discussion a month or two ago with Health Minister George Abbott, but said she was only told the province is looking at ways to better use Riverview.

“If they [patients] were getting the supports they needed, had structure and were treated in a way that allowed them to be as independent as they could cope with, we would be very pleased,” she told The Sun earlier.

“Our citizens … have always been advocates that there be services for mentally ill clients and the phasing out of Riverview was inhumane and the gaps werent filled.”

“At its peak, that site housed thousands of clients …,” she added. “Its always worked in the past.”

Coleman has also suggested that Vancouvers mayor, who has been advocating the creation of more housing at Riverview to ease the social stresses in the Downtown Eastside, butt out. He said it is up to Coquitlam residents to decide how the mental hospital can be best utilized.

“Thats why I take some exception sometimes when the mayor of Vancouver makes his comments about Riverview,” he said. “Riverview is located in the City of Coquitlam. Its not located in the City of Vancouver. The City of Coquitlam will have the public hearing process…. at the front end, in the middle and right through the rezoning process…”

“Were not going to push something down the throat of that community.”

Coleman also indirectly criticized Sullivans earlier musings that some Downtown Eastside residents could be put into Riverview quickly. He was critical of people who “simplistically say move a bunch of people into the empty buildings and let them live there from the Downtown Eastside.”

“It is a non-starter for us,” he said. “I toured the site. And there would be no discussion in regard to doing that. One of the sites … has asbestos, and would probably cost $5 million to tear down and remediate….Some of the old sanatorium buildings have, quite frankly, rats in them…”

Vancouvers dearth of social housing for the poor and shortage of institutional space for the disabled — there are about 13,800 people on the waiting list for social housing across B.C., about 9,000 of them in Greater Vancouver– has drawn international attention in recent months, as Vancouvers 2010 Olympics approach.

Downtown businessmen complained last summer that “aggressive panhandlers,” many of them homeless and suffering from mental disabilities and drug addiction, have been hurting the citys tourism image and cost the province a major convention.

The Economist, a global magazine that has often praised Vancouver as one of the best cities to live, also took politicians to task last year for the grinding poverty in the downtown core.

Not long after that, Premier Gordon Campbell made a major announcement that he was reviewing how the government was dealing with its most vulnerable citizens.

Coleman said that led to both a review of how to better utilize Riverviews land and kick-started a sudden buying spree by the province of rundown hotels in Vancouvers Downtown Eastside that are now being redeveloped by Colemans ministry to deal with the housing shortage for the poor.

But that has not satisfied anti-poverty activists in Vancouvers Downtown Eastside, a neighbourhood that is home to some of the citys poorest and have accused he government of only reacting to the social crisis because of the approaching Olympics. On Thursday, one of Vancouvers most powerful advocates for the citys poor accused the Liberal government of not doing enough.

“Can the tourism industry stand 60 more international articles exposing government treatment of the Downtown Eastside?” the organizers of the Carnegie Community Action Project asked.

“In the last month, both the Washington Post and the UN Population Agency have recently exposed Vancouvers Downtown Eastside as an area where residents endure horrible living conditions in the midst of a wealthy city and country.

“If similar coverage continues for each of the 30 months until the Olympics, that would be at least 60 more international audiences to learn about how government treats poor and homeless people in Vancouver.”

© The Vancouver Sun 2007