John Mackie

Sun

The conservatory of the Shaughnessy mansion that Yosef Wosk is renovating was originally all glass. Photograph by : Ian Smith, Vancouver Sun

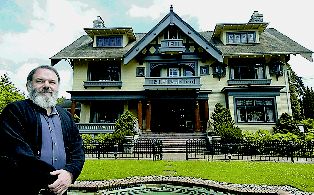

Yosef Wosk is renovating a lumber baron’s Shaughnessy mansion built in 1913-14 with fir columns and an oak and leaded-glass entrance. Photograph by : Ian Smith, Vancouver Sun

The playful wooden lion from a pub in England is placed in the living room near a silver menorah and a toy chariot and horses. Photograph by : Ian Smith, Vancouver Sun

A sculpture of a man serves as the base for a table in the Wosk mansion’s conservatory. Photograph by : Ian Smith, Vancouver Sun

The elaborately carved wood fireplace mantelpiece was created by Scottish craftsmen, and says, ‘East,West, Hame’s Best.’ Photograph by : Ian Smith, Vancouver Sun

An elaborate newel post and curved ‘Juliet balcony’ or ‘minstrel gallery’ for musicians top the staircase in Yosef Wosk’s renovated mansion. Photograph by : Ian Smith, Vancouver Sun

The most substantial renovation in the mansion occurred in the library, which features a chair from India with lion heads on each arm as well as on the headrest. Photograph by : Ian Smith, Vancouver Sun

The dining room also has an elaborate fireplace, a coffered ceiling and leaded glass windows from floor to ceiling. Photograph by : Ian Smith, Vancouver Sun

VANCOUVER – Frank Llewellyn Buckley took out the most expensive building permit in the Lower Mainland in 1913. And he got quite a house for his $30,000 investment.

Dubbed Iowa, after his home state, the 9,500-sq.-ft. mansion was one of the showpieces of the new Shaughnessy neighbourhood. The exterior was rather impressive, with mighty grooved fir columns, a grand oak and leaded-glass entrance and two tiers of balconies. But the interior was something else again.

Buckley was a lumber baron and chose only the finest wood for his new home. The foyer was panelled in “fumed oak,” and featured an enormous tiled fireplace, one of eight fireplaces in the home. It was so big, it could double as a ballroom, and came with a curved “Juliet balcony” or “minstrel gallery” on the second-storey landing where musicians could be installed.

The living room was not quite as big as Napoleon’s tomb and featured an elaborately carved wooden fireplace mantel that read “East, West, Hame’s Best.” (Buckley was American, but evidently his carvers were Scottish.)

The dining room had one of the most amazing built-in cabinets you’ll ever see in your life, as well as another stunning fireplace and leaded glass windows that stretched from the floor to the ceiling. Naturally, it had a coffered ceiling, as did most of the downstairs rooms.

As magnificent as it all was, when Buckley moved out in 1939, the house fell into a bit of a funk. It was a rooming house for a while, then it became an Icelandic Old Folks home. The Daughters of the House of St. Mary operated it as a rest home into the 1970s, then it became a private home again. It passed through several hands until it was sold to its current owner, Yosef Wosk.

A scion of the Wosk department store and real estate empire, Wosk is a unique individual, a well-travelled man who has spent a lifetime in the pursuit of knowledge.

His biography when he received the Order of British Columbia notes that he is a “rabbi, philanthropist, author, community leader, religious art consultant, bibliophile, musician, businessman, and an academic who is director of interdisciplinary programs in the department of continuing studies at Simon Fraser University.”

One thing the bio left out is his interest in heritage issues. Which is why he purchased and has undertaken the restoration of one of Vancouver‘s great houses.

Wosk has hired an elite crew of heritage experts to research the home and get the restoration right, including John Atkin, Don Luxton and Robert Lemon. Eric Cohen and Robert McNutt of Architectural Antiques have provided guidance with the lighting.

The home was designed by architects James C. Mackenzie and A. Scott Ker and was constructed in 1913-14. Atkin says it’s a blend of North American and English arts and crafts, along with a touch of California bungalow and American gothic.

“It’s a real hodgepodge of a house,” Atkin says. “An extraordinary piece of construction.”

A 1975 story in the Province newspaper says the total cost of construction was $80,000, a fortune at a time when a substantial home would sell for $12,000. But Buckley could afford it, because he was a very well-connected industrialist.

“He had the lumber concession for the Queen Charlotte Islands, what we call Haida Gwaii,” says Wosk.

“So he put a lot of nice wood into this. He had Scottish wood carvers come in, so there’s all this magnificent hand carving.”

Wosk decided to live with the house for awhile before he did anything major.

“When I moved in I realized that I had to live here for awhile for . . . it may sound trite, but for the house to speak to me,” he says. “For the house to suggest this is what the room is going to be used for. Then, as my children grow, the house evolves with them.”

It helps that the house was in fairly good shape when he moved in. The oak panelling in the foyer had actually been taken down when it was a care home so that it wouldn’t be damaged. The stained glass and leaded glass windows are well protected from the elements, so they are still in excellent shape.

But there are lots of projects. One was the big columns at the front, which had been covered in several layers of paint over the years. They were stripped down over three months to reveal the beauty of the natural wood. The oak front door and leaded glass sidelights were also restored.

Luxton put together the Vancouver Heritage Foundation’s True Colours heritage paint program, and helped Wosk with the exterior colour scheme. They settled on a “Dunbar buff” cream base with “Hastings red” and grey accents.

“I wanted to restore it to authentic colours, without being obsessive about things,” says Wosk. “I want the house to be livable.”

Many of the original lights had been changed, and Cohen helped Wosk find several period arts and crafts fixtures. The dining room has a string of small lights along the top of the built-in cabinet that seems totally out of character in a mansion, but it is original and will stay.

“When I first saw this I thought ‘What has someone done, come in and put in these chintzy lights?’ ” says Wosk.

“Then I began speaking with Eric and Robert, and they said ‘No, electricity was still pretty new [in 1913], so it was the kind of thing [you’d show off].’ Today you’d say ‘Come and look at the new computer, or the new home theatre,’ then it would be ‘Come over and look at the electric lights.’ “

The most substantial reno has been in the study, where Wosk has built a library that wraps around the whole room with floor-to-ceiling shelving. You reach the upper shelves by scaling a “dream ladder” that slides along on a high rail.

“I felt it was a time in my life when either I was going to build a good library, or not,” says Wosk. “It looks like it’s been here forever; the wood darkens over time.”

Most every room is brimming with antiques, one of Wosk’s passions. But he’s not precious about them: in the living room he’s placed a playful wooden lion that came from a pub in Sheffield, England, near a beautiful silver menorah and a ornate metal “Indian temple toy” with a chariot and horses.

“Apparently when the parents went to worship at the temple, the kids could play with these toys,” he says.

It’s a grand, historic home, but a livable one. The former servants quarters on the third floor have become a rec room for his kids, complete with a pair of Mama chairs, an ultra-groovy 1969 design by Italian Gaetano Pesce that takes the contours of a woman’s body (you sit in her lap).

Naturally, there are also a couple of pinball machines.

“It’s nice in a heritage home,” he says.

“Because you’re always dealing with computers, the Internet, television and everything, [it’s nice to have] a game that takes you back, even one generation, or a book, a piece of art. I’m not necessarily talking about nostalgia, it’s just that there’s a comfort level there. When you’re always on the leading edge, there’s a tension, there’s a stress. It’s comforting to have them around.”

His antiques come from all over and in all shapes and sizes. He picks up a cane with a serpent’s head from China.

“I was taking it on the plane,” he said.

“They said, ‘No no no.’ I said, ‘Why, it’s just a cane.’ So he went like this [and takes a sword out of the cane]. I thought they were going to arrest me.”

In his living room is a Mexican cabinet that he found in a Southern California store called Arte de Mexico. Inside are his most treasured artifacts, his collection of Jewish torah scrolls.

“This was our first one,” he says.

“There was a gypsy who was renovating an old home in Budapest, and he broke into the attic to see what was there. He found this torah, a scroll inside, and 10,000 scraps of leather parchment that had been written on by a scribe there, as well as a number of books. He sold the books to a dealer in New York and I bought the torah.

“My father [helped], I couldn’t afford it. My son had just been born, so we called it Avi’s torah.”

Wosk frets that he gets so carried away with his antiques he sometimes puts too many of them in a room. But he reasons it’s a learning process; he’s spent the last 18 months working on the home, and expects to spend another two years before he’s finished.

“Sometimes I get totally frustrated,” he says.

“At other times the sun comes through and there’s a moment that’s like an epiphany and I’m so absolutely happy to be here, and to be a custodian of the home.

“Because it’s humbling to be in a heritage home. You know that people have lived their lives there, and they’ve gone on and history will change.

“If I do a good job keeping it up, then there will be many more lives lived here.”

HISTORICAL TOUCHES INCLUDE ORIGINAL INTERCOM SYSTEM

Some facts about Iowa, the Shaughnessy mansion owned by Yosef Wosk:

– It was built in 1913-14 by Frank Buckley, a wealthy lumber baron and industrialist in Vancouver. According to the 1914 book British Columbia From The Earliest Times to the Present: Biographical (S.J. Clarke), Buckley was the managing director of the British Columbia Lumber Corp., president and general manager of the Iowa Lumber and Timber Co., president of the Vancouver Arena Co., vice-president and director of North American Securities, and a director of the Great Northern Railway.

– The Buckleys lived on the first two floors, and the top floor was used by their servants. The grand staircase was used by the owners, while the servants used a smaller stairwell tucked into the back of the house.

– The main floor has a foyer, living room, dining room, glass-topped conservatory, kitchen and library. There is leaded and stained glass in virtually every room and in the built-in cabinetry. There is an incredible stained-glass skylight on the second floor that illuminates the grand stairway.

– The third floor still has its original Northern Electric intercom system that the Buckleys could use to call the servants. There is a button on the floor at the doorway from the dining room to the kitchen that the butler hit with his foot to open the door when his hands were full.

– In the 1970s someone put in a long, slender pool in the front of the house that stretches from one end of the property to the other. It features beautiful tile work and a little foot bridge. It was apparently modelled after the moat at Hearst Castle in San Simeon, Calif. “My brother Ken said for my moving-in present he was going to buy me an alligator for the moat,” says Wosk.

– In 1975, the house starred as a Russian embassy in one of Vancouver’s earliest feature films, Russian Roulette, which revolved around a plot to kill then Russian premier Alexei Kosygin. The highlight of the film is when George Segal chases someone across the roof of the Hotel Vancouver.