Scott Simpson

Sun

Startling new research from the Geological Survey of Canada shows that Vancouver International Airport and other large facilities along the lower reaches of the Fraser River delta are falling below sea level much faster than previously imagined.

The airport could find itself more than 130 centimetres below the high-tide mark in the Strait of Georgia by the end of the century — and research indicates that low-lying land along the Fraser as far upstream as Maple Ridge and Langley are also sinking.

Studies this year by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predict a sea-level rise of about 16 centimetres by the end of the century due to global warming — water expands as it gets warmer.

The difference for communities along the Fraser delta — and a handful of coastal venues in Canada — is that they sit on soft land that is sinking under its own weight.

When you couple rising seas with sinking land, you get a double whammy in terms of future threats to urban development as the ocean’s high tides creep farther inland.

The data shows that the weight of a building is the critical factor — single-family homes aren’t facing the same kind of impacts, according to Stephane Mazzotti, a Sidney-based researcher with the Geological Survey of Canada.

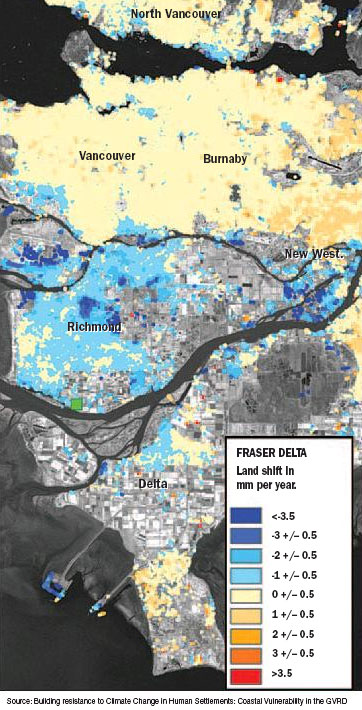

In a telephone interview, Mazzotti said the Fraser delta is “subsiding” at a “background rate” of one to two millimetres per year — compounding a global average sea level rise of 1.6 millimetres per year, or 16 centimetres by 2100.

But Mazzotti said the average number belies greater impacts in some areas of the delta that bear a heavy load of human activity — even where methods such as preloading construction sites with large amounts of earth are expected to settle them prior to construction.

“Some areas are experiencing faster subsidence — up to five millimetres per year and higher — due in part to heavy construction loads,” he said.

Mazzotti and his research group base their findings on several measurement techniques including laser surveys, global positioning measurements and radar satellite images.

They’ve singled out the airport as a site of greatest impact because it’s big and easy to pick out on a radar image, and have similar findings for BC Ferries’ Tsawwassen terminal and the Roberts Bank coal port.

Mazzotti said the group has results for “most buildings in Richmond and Delta” — but hasn’t identified them individually.

The subsidence phenomenon is restricted to low-lying areas along the lower Fraser that are young in geological terms — less than 10,000 years of age — and rely on dikes for protection.

They’re sinking because they are cut off from the nourishing loads of sand and gravel that the Fraser used to deposit on them each year before the river’s edges were bordered with dikes.

Areas with older geology, in the Fraser uplands, aren’t affected by subsidence, Mazzotti said.

“In an untouched delta the surface of the delta is going down but at the same time there are floods that will bring in more sediment so that the average level is kept about the same [in relation to] sea level,” he said.

“Once you put some dikes around it’s still compacting but you don’t provide the extra sediments so that the actual surface is going down.”

He said the group is planning to submit its work for publication in a scientific journal, and has already discussed its findings with Delta, Richmond and Metro Vancouver.

Municipal officials have known for many decades that the Fraser delta is sinking — the Geological Survey released a report in 1973 saying that Richmond was “slowly sinking into the sea,” according to Vancouver Sun archives.

That report suggested the island city was subsiding at the rate of about 30 centimetres per century — and did not foresee rising oceans or local impacts such as a faster rate of sinking at the airport.

The next phase of the survey’s new project will be to examine the behaviour of dikes along the Fraser and the Strait of Georgia foreshore to determine if they are also sinking relative to sea level.

© The Vancouver Sun 2007