Private sector and government building budgets hurting as costs rise

Derrick Penner

Sun

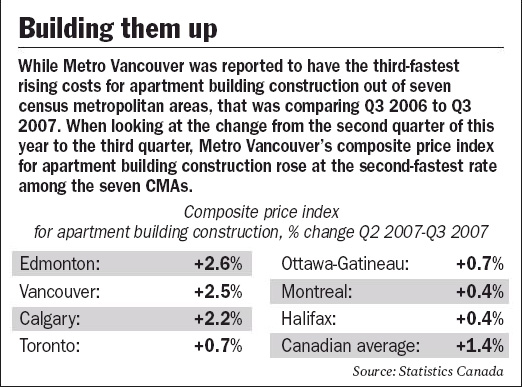

Inflation in construction costs will eat up about half of the growth expected in spending to build new offices, shops, schools and roads in the next two years, according to Credit Union Central B.C.

That means that while investment in non-residential construction is skyrocketing, project owners will have to spend more and build less.

“What [inflation] does,” Dave Hobden, an economist with Credit Union Central, said in an interview, “on the flip side of raising current spending, it also has the tendency to lower real growth, the quantity of investment.

“Because, at the margins, some projects don’t fly if you have that kind of inflation environment.”

Credit Union Central is forecasting that non-residential construction spending will hit $16.3 billion by the end of this year, an increase of 19 per cent from 2006, and reach $19.3 billion for 2008, another 19-per-cent rise.

However, Hobden added that with estimates for inflation in non-residential construction costs to run 10 per cent by the end of this year and rise another 11 per cent next year, inflation accounts for more than half of the gain for costs.

That rate of inflation makes it hard for both private sector and public sector builders to budget for their capital projects.

Hobden noted that governments at the provincial and federal level are running surpluses, and “can handle [inflation] without any serious harm to other types of spending.”

However, municipalities are struggling to keep up with the cost of replacing crumbling infrastructure, as well as building new roads, bridges and skating rinks.

“The thing that’s of greater concern for me is [cost] escalation on projects that have a long lead time between budgeting and the start of construction,” Tom Tim, general manager of engineering services for the City of Vancouver, said in an interview.

He added that for municipal purposes, Vancouver doesn’t put more than a Consumer Price Index inflation factor into project budgets, which in the current context “doesn’t keep up with construction costs.”

So when actual costs break budgets — such as the Trout Lake skating rink renovation, which saw costs balloon to $15.9 million from $10.9 million, and the Killarney rink renovation, which went to $16.5 million from a budget of $14 million — “after the fact, you have to come up with funding and find money from other places,” Tim said.

Vancouver will also face inflation shocks for its Burrard Street bridge refurbishment and Granville Mall reconstruction, both of which were budgeted years ago, Tim added.

And the inflation is being driven by the building boom, which is still robust by any measure.

Jock Finlayson, executive vice-president of the Business Council of B.C., said seven of the 10 fastest growing industries in B.C. are either in the construction sector, or supply construction.

“That tells you the single biggest engine driving this economy is construction,” Finlayson said.

However, Finlayson also characterized the construction sector as overheated at the moment, while B.C.’s trade sector is being hammered by Canada‘s high dollar and by the housing recession in the United States.

“It would be better for the province, going forward, if we would see more growth in the broader economy, particularly in tradeable industries,” he said.

Hobden said B.C.’s slowing trade sector is increasing its trade deficit, which means the province is importing more than it exports, but the domestic economy appears strong.

The deficit “would only become noticeable if consumer demand and domestic demand were to fall off, and we’re not forecasting that,” Hobden added. “We can continue to finance a trade deficit for many years and decades to come.”

© The Vancouver Sun 2007