It takes an icon to know another

Gordon Price

Sun

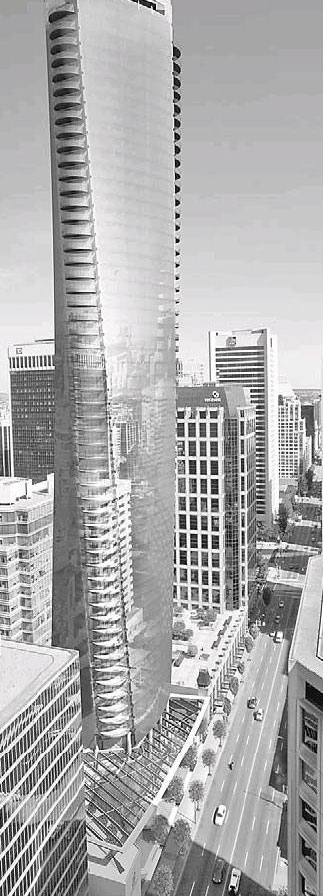

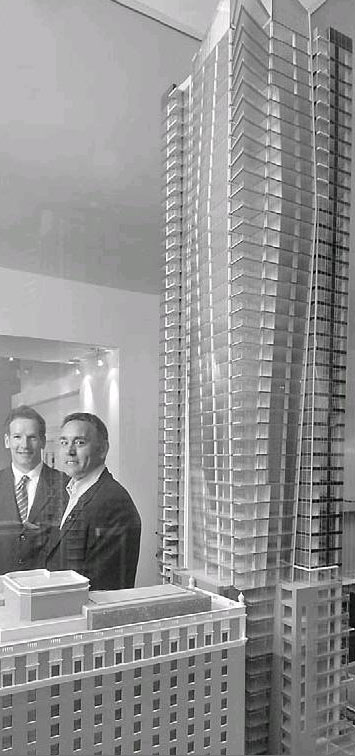

In the new millennium, city hall relaxed restrictions on the height of downtown Vancouver buildings. Above, the Ritz-Carleton project, Below The Georgia new home project.

Your eyes won’t have to drift very far from this column, I’m betting, before you find the word “iconic.”

These days, developers and their marketing departments all want something iconic — at least the imprimatur, if not necessarily the architecture. Some will simply name the building after the “I” word and call it a day. But assemble a group of architects, and you can be sure that they’ll bemoan our icon deficit. Too much green glass, not enough titanium.

Some architecture students even held an international competition recently — “pototype” — to challenge the prevailing orthodoxy of the “Vancouver style.” At a panel discussion, all agreed: Vancouver may be good at background buildings, but how about something gutsy in the foreground?

Or at least something taller. That was the option Vancouver pursued at the beginning of this century, when the traditional downtown height limit was shattered in return for a commitment to more adventurous architecture. You’ll be able to judge for yourself on Georgia Street, when at least three new super-talls open around the Olympics.

But one voice is already urging caution — and it’s a voice worth heeding. It comes with perspective.

Ray Spaxman was recruited as city planner by Vancouver‘s leadership in 1973, when the public was in full flight from the excesses of modernism and out-of-control development.

Only a decade and a half previously, the tallest building in the West End was the Sylvia Hotel. (“Dine in the Sky” said the sign on the roof.) And not many people thought several hundred concrete slabs had really improved our urban ambience all that much.

Spaxman was responsible for changing the way planning and development was done in this city — and he summed it up in one word: “neighbourliness.” A building had to be respectful of its neighbours, and of the citizens on the street. Nothing expresses that better than the canopies which now make it possible to walk downtown on a rainy day without having to take an umbrella.

Buildings, in other words, had to be more than sculptural objects on vacant plazas — “pigs in space,” as some planners call them. It didn’t matter how “iconic” a building was if it selfishly ignored the urban environment in which it dwelt. The best bad example: the original Eaton’s at Pacific Centre, with its acres of blank white walls. Very iconic, very unfriendly.

Spaxman fears that “iconic” may be just a shorter word for ostentatious.

His contributions to Vancouver are, as they said of another English architect, all around us if we only look.

Spaxman served at city hall for 16 years, he transformed a bureaucracy, and he trained a generation of planners who carried on his legacy.

By any standard, he deserves the title of “Paradise-maker” — one of those leaders from the 1970s and ’80s who not only felt an obligation to maintain the quality of life and the environment in the Lower Mainland, but to make it better.

– – –

Former Vancouver city councillor Gordon Price is director of the City Program at Simon Fraser University. He prepared these comments on the occasion of a public ”interview” of Ray Spaxman

© The Vancouver Sun 2007