David Spaner

Province

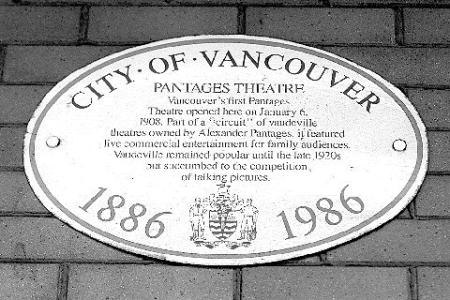

The heritage plaque on the side of the Pantages Theatre building at 144 East Hastings Street. Photograph by : Jon Murray, The Province

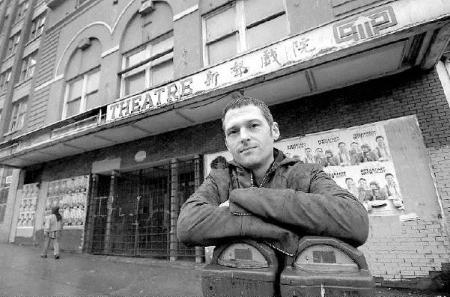

Tony Pantages, great-nephew of theatre founder Alexander Pantages, outside the shuttered former entertainment palace near the corner of Main and Hastings. Photograph by : Jon Murray, The Province

The rise of the Pantages will be something to behold.

Step through its battered, boarded-up facade near Main and Hastings, and there are remnants of a “palace.” When the Pantages Theatre opened — 100 years ago come Jan. 6 — Hastings Street was the city’s lively main drag and the ornate new theatre its jewel.

Now it’s on the road to being restored to its former grandeur.

“It’s eminently restorable,” says Vancouver historian John Atkin. “It’s a building that was built extremely well.”

—

I first set foot in the Pantages back in the pre-VCR 1970s, when it was called the City Lights Theatre and screening then hard-to-find foreign films and Hollywood classics. It still had a grandeur, albeit a tattered one, and I remember looking at its opera boxes, high ceiling and plaster wall decorations, and wondering: What was this place?

Now I know the Pantages Theatre was a movie palace. In the first decades of the 20th century, the movies were new and theatre designers naturally assumed that one should put the same care into building a movie theatre that went into an opera house. In an age of small, multiplex screens, it may be difficult to imagine the magnificent movie palaces that were constructed in those years across North America. By the late 1920s, though, theatre owners realized an unadorned room could draw movie audiences just as well and the age of luxury was over.

Over the years, a couple of Vancouver‘s palaces were saved after long public battles (the Orpheum, the Stanley), and more were levelled, including the Strand, the Capital, and a second Pantages further west on Hastings. “The second Pantages made the Orpheum look like a hick-town theatre,” says Atkin. “It was really quite something.”

Tony Pantages lives in Strathcona, a few blocks from the grand theatre at 144 East Hastings that’s been linked to his family for a century. He’s also a filmmaker who’s spent considerable time researching a film he’d like to make about Alexander Pantages, his great-uncle, who built the theatre. “He builds a bunch of theatres, becomes incredibly wealthy,” says Pantages. “Vancouver was almost a testing ground for how the chain expanded.”

Alexander was a larger-than-life character — born in Greece, ran away from home at nine to work on ships, eventually wound up in San Francisco, where he bartended on Cannery Row. When word of the Klondike gold strike arrived, he headed north, where he had a relationship with legendary saloon madame Klondike Kate. Fortune in hand, they left the Klondike, then Alexander left Kate. She opened a vaudeville house in Vancouver; Alexander opened the first Pantages Theatre in Seattle.

Vancouver was a rougRating 2 ewn port town, barely out of the Wild West era, when the 1,200-seat Hastings Street Pantages opened, the second in Alexander’s chain that would grow to 72 ritzy theatres. “It must have been testy, ’cause Klondike Kate was still here with her theatre,” Pantages notes.

When the even more luxurious second Pantages Theatre opened down the street in 1917, the original Pantages at 144 East Hastings became the Royal. In succeeding decades it would be a burlesque house (State Theatre), first-run cinema (The Queen, Avon), revival house (City Lights) and Asian cinema (Sung Sing). In 1989, following a flood, it was shuttered. “That’s when their boiler blew up, flooded the basement,” says Atkin.

Mixing the movies, which were brand new, with travelling vaudevillians — comics, musical acts, magicians — was a winning combination for Pantages, and his movie/live theatres became a big part of the vaudeville circuit. “That’s why he made it,” says Tony. “He basically could see what was going to happen.” His two Vancouver theatres would bring to the city everyone from Charlie Chaplin to Babe Ruth to Laurel and Hardy.

When the Pantages opened on Jan. 6, 1908, The Province noted: “When the orchestra at Pantages‘ new vaudeville theatre sounded its first note last night, an audience that filled every seat in the splendid house vouchsafed its appreciation of the opening of the theatre with applause that only subsided with the raising of the curtain.”

True to Pantages‘ form, that first night, the “modern vaudeville” was combined with the “latest moving pictures.”

“The moving pictures,” said The Province, “are good subjects but very poorly presented. The management promises to improve them before tonight’s performance.”

I’m not so sure the movies have improved since then and vaudeville is dead, but the Pantages is still around, and about to make its presence felt. While the Pantages Theatre Arts Society, which has signed a long-term lease agreement with owner Marc Williams, is reluctant to speak publicly about the theatre’s revival until negotiations with the city are finalized, it is known that they have strong roots in the Downtown Eastside community.

Their plans include fully restoring the theatre, reducing the original seating capacity with the installation of comfortable new seats, providing free parking to theatregoers and offering free tickets to local residents. Hopefully, it will retain the legendary Pantages Theatre name.

If the negotiations are completed by January, as expected, the three resident companies will be the City Opera of Vancouver, the Vancouver Cantonese Opera and Vancouver Moving Theatre.

There is something to be said for a neighbourhood that developers consider “undesirable.” While the rest of Vancouver was being diced, sliced and redeveloped, this neighbourhood, which had evolved from the city’s hub to its skid row, drew no interest from developers with wrecking balls. So, the streets are lined with blocks of tattered-but-beautiful old buildings.

“You know what saved this one [the Pantages] — atrophy,” says Tony Pantages. “The fact that nobody cared about that block any more.”

It’s the oldest surviving vaudeville/movie house in Canada and the oldest surviving Pantages Theatre, period, retaining a semblance of its plaster decorations, balcony and opera boxes. “It’s all there, which means you can use it to create a proper restoration,” says Atkin.

“It’s the only theatre left on Hastings Street,” Atkin continues. “Hastings Street was equal to Granville Street right through until the 1930s, the 1940s. You had over 18,000 live-

theatre seats on Hastings Street. That was your entertainment centre.

“The neighbourhood itself is quite interesting, architecturally. And I think the theatre stands a chance of being something very successful in the neighbourhood.”

While the city has drawn up plans for 10,000 condos in the area and developers are poised to create a mix of storefronts and housing, residents are concerned. Most everyone who lives in the Downtown Eastside agrees improved housing is the first step toward addressing drugs and other problems.

“It’s an amazing sense of community,” says Pantages. “It’s the best neighbourhood I lived in in my life, and I’ve lived in West Vancouver, lived in Beverly Hills, lived in Soho.

“We restore the Pantages Theatre but we also build something for the people that need a hand.”

The Pantages family is more than a theatre. Tony’s grandfather, Peter, arrived in Vancouver from Greece to work at the Pantages. “Looking from Kits to West Van reminded him of Greece,” says Pantages. He stayed and founded the annual Polar Bear Swim at English Bay and the Peter Pan Cafe, a Granville Street mainstay for decades. He would have four children, including lawyer Tony Pantages, filmmaker Tony’s dad.

Pantages‘ film work includes music videos and commercials. He’s just returned from L.A., where he directed a Behind the Scenes TV documentary about the making of Tin Man, a new Wizard of Oz miniseries.

Pantages, born in 1963, had never been inside a Pantages theatre when, in the 1980s, he moved to Los Angeles to become a struggling actor. He often hung out at the Frolic Room bar, near the glitzy Pantages Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard.

“I never went there. Couldn’t afford it,” he says. “One night, it’s 10 o’clock and the bartender at the Frolic says, ‘You gotta go in there.’ So, I went up to the door, showed my passport, said my name’s Tony Pantages, my family built this theatre and I just want to come in and take a look . . . A security guard grabs me and throws me right out of the theatre . . . I’m sitting there thinking, ‘I’ve still never been in a Pantages Theatre.'”

Years later, he would see the Bolshoi Ballet at the Hollywood Pantages, and may soon see the Pantages in his hometown.

“Everything’s a cycle. I just worked on a new Wizard of Oz movie,” he says. “Who would have figured they would have an ornate palace in the middle of a frontier town? So, who would figure they would have an opera company and theatre company in the poorest postal code in North America?

“It’s the same thing. I think it’s brilliant. It’s an anchor. You have to have the arts to have a community.”

© The Vancouver Province 2007