Lower Mainland farmers can sell property for $50,000 to $70,000 an acre

Derrick Penner

Sun

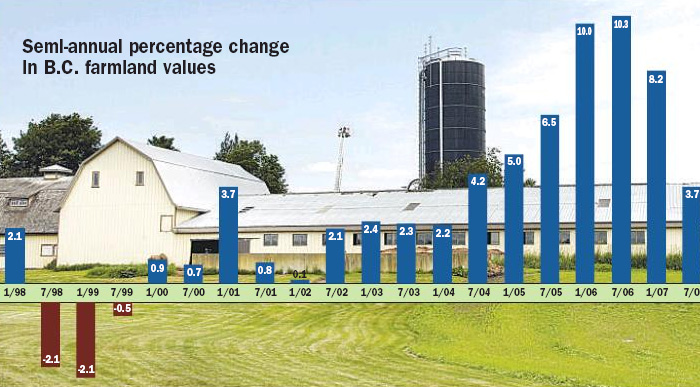

Source: Farm Credit Canada – VANCOUVER SUN

It is a comfort for B.C. farmers — although perhaps a cold one in today’s tough times — that they’re getting richer because the land they’re sitting on is worth a growing fortune.

In a familiar B.C. real estate story, provincial farmland values increased almost 55 per cent in the five years between mid-2002 and mid-2007, according to Farm Credit Canada‘s semi-annual appraisal of benchmark properties.

The steepest curve in that rise began in 2004, with the peak occurring in 2006, when values climbed 10 per cent in the first half of the year and another 10.3 per cent in the second half.

But the inflation of land values has eased somewhat, with the first half of 2007 showing only a 3.7-per-cent increase.

“Certainly the most expensive farmland in the country is here [in B.C.],” Bill Wiebe, a Farm Credit Canada senior appraiser, said in an interview.

B.C. farmland values have been driven up by the province’s booming blueberry sector, Wiebe said, as well as increased foreign investment and the strong performance of the provincial economy. More people have enough money to buy into farms and the rural lifestyle, even though most don’t intend to make a living from farming.

However, while growth of land values has given farmers a more valuable asset, the rise makes it difficult for new participants to buy into a greying industry. It also hinders farmers’ ability to pass their operations on to the next generation.

Wiebe hesitated to estimate average land values because they vary widely depending on location, size, and crops, but Gord Houweling, a realtor who specializes in agricultural land, cited some dramatic examples.

Houweling has seen prices for Matsqui-area farmland top out at $70,000 an acre, after selling for $25,000 to $30,000 just five or six years ago. Houweling has sold land for as much as $120,000 an acre, although that was a smaller blueberry field with a crop ready to be picked.

B.C.’s blueberry sector has been booming, increasing demand for land to grow the fruit now touted as a healthy super-food. And Wiebe noted that higher foreign investment in B.C. agriculture is also pushing values up, although farming as a business in general is going through some tough times.

Statistics Canada, in its latest report on farm balance sheets, said the total equity farmers have in their operations — the value of their land and equipment that is in excess of their debts — increased in 2006 largely because of rising land prices.

However, in another report, Statistics Canada found that in 2006, for the second year in a row, farmers’ cash income from crops and livestock declined.

But it is the seeming stability of that land investment, Wiebe added, that keeps people coming into agriculture.

“Even if some years are tough cashflow-wise, they still feel they have a solid investment in the base of that [farm] business,” Wiebe said.

Steve Thomson, executive director of the B.C. Agriculture council, said B.C.’s beef and pork producers in particular have experienced hard times with prices that have declined at the same time costs in fuel and animal feed have risen precipitously.

“If you’re really struggling in terms of providing a return to labour and a return to investment [rising land prices] puts pressure [on farmers] to sell,” Thomson said.

However, selling at high market prices reveals farming’s other great challenge: trying to attract new farmers.

“There are real challenges in being able to afford to come in,” Thomson said, adding that the people who can afford to buy the land aren’t necessarily the people who plan to work the land as intensively as the previous owners.

the increasing land values offer different choices. Houweling said in recent years he has worked with a handful of dairy farmers who have sold Fraser Valley operations for $50,000 to $70,000 an acre and relocated to other, less expensive locations.

Dairy farmer Ken DeRuiter is one example. In April of last year, he traded the family farm — a 60-acre dairy operation on Matsqui Prairie north of Abbotsford — for a 175-acre property just outside Armstrong in the north Okanagan.

DeRuiter said he sold the Abbotsford property and moved because his options for staying in the Fraser Valley were limited by the high cost of land surrounding his dairy.

He considered buying land to expand, but one 18-acre property for sale was $1.5 million. However, if he bought that bit of land, he wouldn’t have been able to upgrade his dairy’s aging equipment.

And though the Abbotsford property was the farm his Dutch-immigrant parents bought in 1975, it was an easy decision for DeRuiter’s family to sell at $65,000 — $70,000 an acre and buy a bigger property with newer equipment that can support more cows for about $15,000 an acre. He milks 110 cows on the Armstrong property, up from 85 when he was in Abbotsford.

“What we were looking for was land,” DeRuiter said. “But you tie up $1.5 million into a little piece of land that’s only 18 acres, you tie yourself up pretty tight.”

And his family was thinking about the future for his children.

“Are they going to be able to farm here [in Abbotsford]? Where’s the future going? Those are all the factors in the decision.”

Houweling said the Creston Valley in the province’s southeast, where land can be had for about $4,000 an acre, is another location Houweling said farmers talk about. And for an aging generation of farmers who are descendants of immigrants, Houweling added that selling the farm represents success in the long-term plan to make sure their children have a better life than they had.

“And you’re seeing in a lot of different sectors, the children are becoming dentists, doctors and lawyers and everything,” Houweling said. “A lot of guys are hitting that 50-year-old mark and have no one that wants to take over.”

He added that a new wave of immigrants, largely from India, and looking for opportunities in Canada, are the biggest group of new buyers.

© The Vancouver Sun 2008