Garth Turner

Sun

What does the future hold for the four-bedroom, three-garage house in the suburbs? Photograph by : Peter Battistoni, Vancouver Sun Files

Imagine listing your home for sale, but there are no buyers. You drop the price. Again. And again.

The house across the street’s now for sale. And the one two doors down, plus a dozen others in a two-block radius.

Nothing’s selling, and every time one home is reduced, all are affected. This property used to represent wealth. Now it’s a wealth trap.

, and with each day passed, it diminishes.

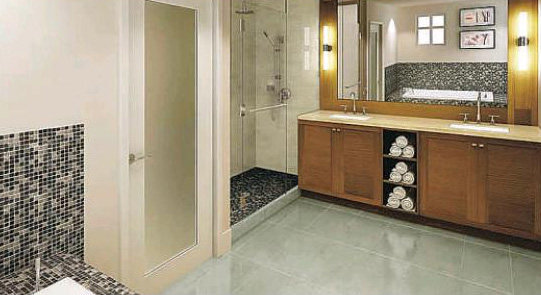

Imagine your first home — a dream in granite and stainless. You bought it from the region’s largest builder, for 1.5 per cent down — enough to cover closing costs — and mortgaged the rest. Months later, the economy turns abruptly. Your spouse loses his job and the monthly payments — mortgage, taxes, utilities — are crushing.

You decide to sell, but the realtor tells you the market has also turned. Your mortgage is now slightly greater than the value of the home. After paying commission, you’ll have no house, no equity, and still owe the bank more than $20,000. How could this have happened?

Far-fetched? Hardly. For millions of middle-class Americans, this is a reality as housing values collapse in the first nationwide housing meltdown since the Depression. In some markets, prices have crashed 30 per cent. In Phoenix, there are more than 20,000 new homes, vacant, unsold and unwanted. In suburban Detroit, million-dollar properties can’t fetch buyers at $300,000. Downtown, prices plunged in the first two months of 2008 by 54 per cent, to a median of $22,000.

In Florida and California, homeowners establish websites to try to sell their homes. Three million American families now have mortgages larger than their home values. Comfortable upper middle-class families with six-figure homes find their wealth evaporated as their properties languish on the market. So many foreclosed homes are for sale, it’s estimated prices will not recover for years. In fact, a recent Credit Suisse report says prices must fall another 40 per cent in Miami and 26 per cent in Los Angeles before they become affordable.

The real estate disaster now in full flower to our south is a fascinating, gripping spectacle. It’s time we looked closely. Because, one way or another, it’s coming here.

Canadians, strangely, believe this country is immune from the housing contagion sweeping America. The myth results from three powerful forces. Denial tops the list, no doubt the result of having more than 80 per cent of our net worth in one asset, the family home. Add to that the excellent communications job done by the real estate lobby — mortgage-lending bank economists and the CEOs of real estate marketing companies — who claim home values will rise forever. Finally, our belief the Americans screwed up by giving subprime mortgages to unworthy people so they could buy unaffordable homes.

But this is not so. In researching my book, Greater Fool, I was reminded again of why all booms end badly. The inflating real estate market to the south became unsustainable when average prices exceeded the ability of average families to buy homes. This inflation in turn was the result of policy decisions made after 9/11 which gave America (and Canada) the lowest interest rates in a generation. Debt was cheap, and volatile stock markets represented unacceptable risk. So, real estate became the asset of choice.

But as interest rates increased, the American economy softened and realization spread that real estate was overvalued. The bubble burst — and with a vengeance.

So, how different is the Canadian experience? In the period between 2000 and the market crash in 2006, U.S. home prices increased 74 per cent, while household income rose by just 15 per cent. In Canada, real estate prices jumped 70 per cent by the end of 2007, with family incomes ahead 14 per cent.

In other words, we’ve seen an almost identical pattern of real estate excess — familiar to anyone caught in a bidding war, or staring in disbelief at a new MLS listing. The average home in Toronto is now over $400,000, while in Vancouver it tops $700,000. Last year homes in Saskatoon raced ahead more than 50 per cent in value. A young couple in suburban Toronto with a $450,000 price limit ended up buying a $700,000 home after losing 16 competing bids.

And the Canadian response to this affordability crisis? It’s called the 40-year mortgage, which lowers monthly payments by extending the amortization 15 years beyond the traditional quarter-century and, in the process, grossly inflates the total debt to be repaid. In other words, this loan (now accounting for over 40 per cent of all new borrowings) allows people to buy homes they would not otherwise afford.

Meanwhile, down payments have become almost optional. One of Ottawa‘s largest new home builders routinely allows young couples to move in by paying just closing costs, and financing the other 98.5 per cent of the purchase price. With virtually no equity in the home and substantial carrying charges, any market downturn means they owe more than they own.

So, how exactly do American subprimes differ from Canadian 40-year mortgages? How are mortgage lenders here more prudent when they allow appraisals based on postal codes rather than home inspections? Why should Canadian real estate values, as inflated now as were those to the south two years ago, hold when our families are no better off? As a global economic slowdown and an American recession take hold, what impenetrable barrier is wrapped around this country?

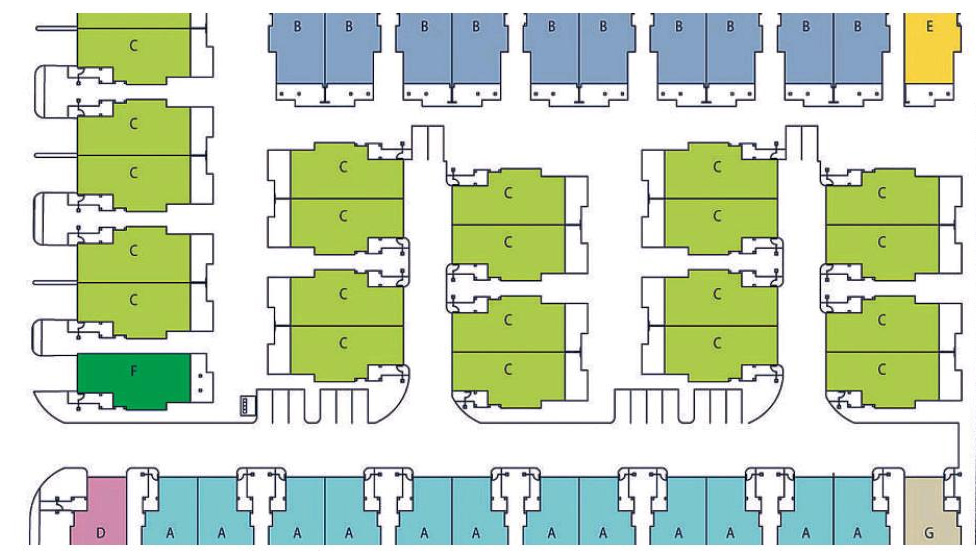

Meanwhile, what about the future? Won’t nine million house-rich and pension-challenged boomers be forced to dump billions in real estate over the coming decade? Won’t runaway energy costs and the uncertainty of climate change breed a popular taste for smaller, more efficient, more urban housing, rendering four-bedroom, three-car-garage suburban palaces unsaleable?

Most of all, won’t those who understand what’s clearly coming, and sell now, rejoice that they found a greater fool?

Garth Turner is the MP for Halton, Ont. Greater Fool: The Troubled Future of Real Estate is his eighth book, published by Key Porter Books.