Our city would have looked very different had these plans gone ahead

John Mackie

Sun

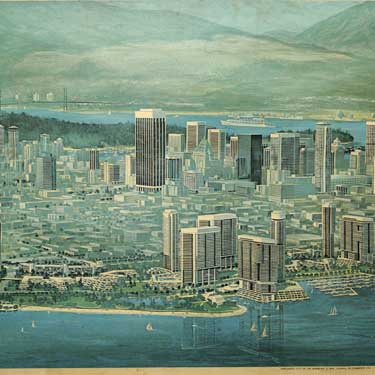

A 1970 drawing of False Creek and downtown showing buildings that were never built. Photograph by : Glenn Baglo / Vancouver Sun

Vancouver has seen its share of Big Proposals over the years. But Premier Gordon Campbell’s recent announcement that the province would be putting a sunroof on BC Place Stadium and had found a new waterfront location on False Creek for the Vancouver Art Gallery ranks with the best of ‘em.

The refurbished stadium and gallery are supposed to be the linchpins for a new “high-density urban entertainment/cultural hub” on False Creek.

Just what that means is anyone’s guess — as is whether it will ever happen. Old newspapers are filled with plans for cultural facilities and concepts that were never built.

One of the recurring themes in Vancouver is the search for a cultural hub or civic centre. In 1929 American planner Harland Bartholomew unveiled A Plan For The City of Vancouver, a planning document that became the blueprint for the development of the city for decades.

One of the key elements in the Bartholomew plan was for a massive civic complex on the north shore of False Creek at Burrard and Pacific.

“That was probably the most grandiose and most complex plan,” says heritage expert John Atkin.

“It would have changed the face of the city completely, in terms of the focus and how things developed.”

The Bartholomew complex included a new city hall and several other civic buildings.

“It was going to contain a museum, archives, I think it was even going to have a library,” says Norman Young, the former chairman of the civic theatres board.

“It was one of those things where they thought ‘We can put everything together.'”

The drawing of the plan by architect George Sharp is very art deco, elegant and streamlined and perfectly symmetrical. There’s a waterfront walkway, formal gardens, a grand staircase, and two banks of civic buildings on either side of the staircase. At the top of the staircase is a block-long city hall, which has a deco tower similar to the city hall that was finally built at 12th and Cambie in 1935.

Unfortunately, the depression came along, and the plan was never adopted. But one element of the Bartholomew civic complex plan was built: the Burrard Bridge.

Sharp and his partner Charles Thompson had a hand in many big concepts. In 1914, they drafted a plan for the University of British Columbia, but the construction of the university was delayed by the First World War and when UBC was finally built in the 1920s, Sharp & Thompson only got to design three buildings (the library, the science building and the powerhouse).

This didn’t seem to deter them. The Vancouver Public Library’s archives have two Sharp & Thompson designs for museums from the 1930s. The Pacific Museum was to be located at Lost Lagoon on the eastern edge of Stanley Park. It was a handsome, imposing structure, very much like the Bartholomew city hall, save that the central tower was relatively low.

Another Sharp & Thompson Pacific Museum was to be located on Deadman’s Island off Stanley Park. It was a much grander design, with an Empire State Building-style tower and an adjoining citadel-style building. It also had a massive park-like interior courtyard.

If Whitecaps owner Greg Kerfoot can ever talk the Port of Vancouver’s bureaucrats into letting him build his waterfront soccer stadium in Gastown, he might want to take a look at Sharp & Thompson’s beautiful 1934 design for a stadium at Kits Point. It was very deco, naturally, but also contained a little bit of everything: a 30,000-seat stadium, a civic auditorium, an outdoor bandstand, a civic plaza, a pool and tennis courts.

But someone should warn Kerfoot that there have been numerous plans for sports stadiums that were kiboshed. Young found a 1911 newspaper story for a 50,000-seat stadium on the Stanley Park side of Lost Lagoon. In fact, it was to be built with fill on Lost Lagoon, or at least the northwestern corner of Lost Lagoon. It was a rather ambitious concept: at the time, the population of the entire Lower Mainland was about 157,000.

“There was another [proposed sports stadium] where this guy had almost all the property where the art gallery is now,” says Young.

“He was going to build a baseball stadium there in the early 1900s. He couldn’t get one or two lots, so he couldn’t do it.”

Park commissioner George Thompson advanced his plan for a civic centre on Georgia Street at the entrance to Stanley Park in 1949. The nine buildings included a library, polytechnic school, theatre, auditorium, museum, art gallery and art school.

None of it was ever built, but Atkin says the Queen Elizabeth Theatre is a leftover from another civic centre concept.

“I think the [current] site of the CBC was going to be a sports arena, a la Key Arena in Seattle,” says Atkin.

“Then there was going to be a convention centre, and an art gallery and library. The Queen Elizabeth Theatre was actually the first piece of that large puzzle, and the rest of it never got built.”

There were several versions of the sports arena near the Queen E. One was a somewhat brazen attempt by the then-owners of the Toronto Maple Leafs, Stafford Smythe and Harold Ballard, to get Vancouver to give them a block of free land, where they would erect a 20,000-seat arena for a National Hockey League franchise. Council put their plan in a plebiscite in the 1964 election, and voters turned it down.

The Sun files have an alternative 1949 plan for the theatre that became the Queen E. It would have had a theatre, but also included a 10-storey public library, CBC broadcasting studios, and stores. It would have been located between Robson and Smithe and Howe and Hornby, where Robson Square is today.

The Queen Elizabeth Theatre is now undergoing a $15-million renovation, but a few years ago, Young says, there were discussions about knocking it down and building a new theatre next door on the former Greyhound bus depot/Larwill Park site.

“This was at the same time they were going to build the [present] library, which is why it never got any press, etc.,” says Young.

“Part of the considerations was to buy the post office and put the library in there, because it’s an adaptable building, along with a million other civic things like the museum and stuff like that. And then rebuild the theatre and change the block between [where the Queen Elizabeth is today] to a park. Nothing ever came of it.”

The old Greyhound/Larwill Park site may yet become some kind of major civic space. Before Campbell gave his surprising announcement that the art gallery was moving to False Creek — the gallery was only told about it two weeks in advance — the new gallery was supposed to be on the Larwill Park site.

Now Mayor Sam Sullivan has mused that the long-delayed Coal Harbour arts complex could go to Larwill Park. It was supposed to be built on the Coal Harbour waterfront, but the land was sold to the province for the new convention centre.

The city still has $20 million it collected from developers and the province for the arts complex, but if the BC Place sunroof costs $200 million, the art gallery costs $300 million, and a new national maritime centre is built on the North Shore, funding for a $70-million mid-size (1,800 seat) symphonic hall might be a bit hard to come by. (All of these figures are educated guesses — Gordon Campbell didn’t release any dollar figures in his BC Place/art gallery announcement. The last time Sun reporter Chad Skelton did a Freedom of Information request about BC Place’s roof, he got back 13 pages of blacked-out documents.)

The art gallery looked at many options before settling on the Larwill Park site, including staying at its present site in the old courthouse at Robson Square. One option featured a new building on the southeast corner of the site. A model of the proposal is wild — the top of the building hangs over its podium like a giant ‘T.’ It was as tall as the Sears building across the street.

There also would have been a new entrance on Georgia Street below the current entrance, so that the basement of the gallery could be incorporated into the exhibition space. Arthur Erickson’s 1983 addition would also have been demolished, bringing the courthouse section of the gallery back to its original 1912 look.

There were many, many plans for libraries that were never built. Architect C.B.K. Van Norman designed an ultra-modern 10-storey library at Burrard and Robson in 1952. The firm of Sharp, Thompson, Berwick and Pratt (a latter-day edition of Sharp & Thompson) designed another modern highrise library in 1946, while Ald. Halford Wilson proposed a sleek modern library at Pender and Beatty in 1951. There’s a parking lot there now.

Wilson’s library is quite striking; it’s really too bad it didn’t go through. But in retrospect, many other Big Plans were kind of dumb. A few years ago I found a poster in a junk store for something called “Vancouver: City of the Seventies.” Essentially it’s an artist’s conception of Canadian Pacific’s plan for the north shore of False Creek in the late ’60s — a beehive of bland concrete apartment towers.

The biggest building downtown was also never built: a controversial 50-storey courthouse proposed by W.A.C. Bennett’s Social Credit government. The idea was killed by Dave Barrett’s NDP when it was elected in 1972.

“The legend is when Wacky Bennett got booted out and Dave Barrett came in, Barrett said ‘this is awful,’ ” says Atkin. “So he took the model of the tower, laid it down on its side and said ‘Let’s build this.’ That’s the origin of what was called the three block project, which became Robson Square.”

Reached at his home in Victoria, Barrett chuckles at the memory.

“Well, actually it was [attorney-general] Alex Macdonald,” says Barrett.

“He came up to me and told me about this. I said ‘Well, hell Alex, if that’s the way you believe [then do it]. You know more about the legal structure and what kind of facilities you want.’ He said ‘Fine,’ and went ahead and did it. They built the courthouse, but not that huge monster they had planned.

“We lost the [next] election, but Alex showed up anyway at the dedication for the [Robson Square] building, and they just ignored him. That was chicken [bleep] stuff. Mind you, they were a chicken [bleep] crew.”

Barrett is now 78, but he still hasn’t lost his bite, or his wit. Asked what the idea was behind the Socred courthouse tower, he replies: “They wanted a phallic symbol, I think. People are hard up, they’ve got to have something.”

© The Vancouver Sun 2008