Working people can afford homes more easily

Lena Sin

Province

Cafe owner Chris Quinlan bought a two-bedroom condo on Blackcomb Mountain for $172,000 through a price-controlled real-estate program in Whistler. — BONNY MAKAREWICZ — FOR THE PROVINCE

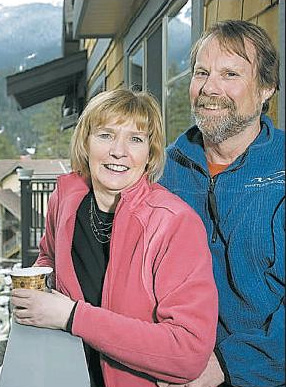

The Whistler Housing authority made Max and Marlene Maxwell’s dream real — BONNY MAKAREWICZ — FOR THE PROVINCE

Chris Quinlan doesn’t look like the kind of guy who would own a spacious, ski-in, ski-out condo perched on the side of Whistler’s Blackcomb Mountain.

That kind of pad retails in the neighbourhood of $750,000 — way more than what most bachelors can afford, let alone one who earns his crust running a coffee shop.

But that’s exactly what Quinlan does for a living as the 44-year-old owner of a funky little cafe in the heart of Whistler Village.

So how did he do it?

For starters, Quinlan didn’t pay market value when he took possession last August — he paid $172,000.

The deal was made possible through a unique program in Whistler designed to ensure homes are kept affordable for the ordinary, working folk who make the town run.

To date, 4,200 people have taken advantage of the program, offered through the Whistler Housing Authority.

What this means is 75 per cent of Whistler’s workforce now lives in the resort — not bad for a town better known for its million-dollar chalets than affordable housing.

“The idea is when you drive people out of your community, you stand to lose the heart and soul of your community,” said Gordon McKeever, a city councillor and longtime Whistler resident.

Long before Vancouver‘s current housing squeeze on families and first-time homebuyers, Whistler was already grappling with how to retain its teachers, nurses and tourism workers in the face of skyrocketing prices.

Fears of “Aspenization” throughout the 1990s led the municipal government of the day to take the bold step of getting into the housing game.

In 1997, the Whistler Housing Authority was created as an arm of the municipal government.

Its mandate was to oversee the development of price-controlled real estate available only to resident employees and their families.

Condos, townhouses and single-family homes were built and sold at cost — and continue to be today.

The catch? Once you buy through the housing authority, resale prices are capped at below-market values.

“It truly is a legacy of affordable housing that will continue in perpetuity,” says Marla Zucht, general manager of the housing authority.

Without the program, couples like Jacki Bissillion and Ken Roberts would’ve been forced out long ago.

“We’re people who started out working in the front desk and maintenance and moved up the ladder and are the typical people who are making this town run,” says Bissillion. “But we were looking at leaving a few years ago because the free market [housing] just was not an option.”

Bissillion works at a local TV station while her husband is an engineer and volunteer firefighter.

They recently purchased an 1,800-square-foot, three-bedroom home, “which we’re in the process of populating,” laughs Bissillion, who is pregnant with their first child. Through the housing authority, the home cost $360,000.

Bissillion is more than OK with the cap on her real-estate investment.

“I don’t want to be that person that has to jump into a car everyday to go to work and jump in the car to go home,” she says. “Certainly living in the Lower Mainland, if you want a family, that’s what you’d have to do — and it’s just not the kind of impact I want on the environment.”

The model set up in Whistler has been used throughout the U.S and parts of Canada as a creative solution for middle-income workers who make too much to qualify for social assistance, yet not enough to afford a home.

The launch in Whistler, however, was not an easy road to go down. The mayor and city council of the day found themselves the target of outrage and NIMBYism as residents feared the kind of undesirables who would find a toehold in their neighbourhoods.

The developers, the primary builders of these homes sold without profit, weren’t too happy, either.

Rod Nadeau, a Whistler developer, says he knows developers who have lost money building in the resort, although he has not.

“Just because you’re building social housing doesn’t mean the guy selling you two-by-fours is going to sell it for cheaper,” he notes.

Max Maxwell, 57, says that to the city council’s credit, it persevered and moved forward with the program.

For sure, mistakes were made along the way.

Today the program is far from perfect, with more than 700 people on the wait list — some have been waiting as long as four years.

But Maxwell, a local columnist, believes it has also made thousands of people’s dreams come true, including his own.

Maxwell and his wife left the corporate rat race in Toronto 16 years ago. They headed west to find their future and landed in Whistler, because “let’s face it, being a ski bum is way better than being a banker.”

“I throw my skis on my shoulders and walk to the mountain.

“How many people can say they get to do that?” he asks.

– – –

HOW IT WORKS:

Raising the funds to build affordable homes in Whistler is done a number of ways.

First, a housing trust fund was established. Developers paid into it for every new commercial, industrial and tourist development that increased the number of workers in town.

The cash was then used to build rental suites or homes to be sold at cost.

More recently, city council has favoured using “density bonusing” to negotiate with developers.

For allowing developers to build more units than what city council would normally approve, the developer in return sells a portion of the suites at cost.

“Their profit on the market side is enough to have them interested,” says Mayor Ken Melamed.

How are you coping with the real estate crunch? What should be done to ease it? Send your story and suggestions to [email protected]