City politicians and staff failed to ensure the project had sound financing from the outset

David Baines

Sun

Vancouver has asked the provincial government to amend the city charter to enable it to borrow the $458 million required to complete the athletes’ village project. Photograph by: Ward Perrin, Vancouver Sun, Vancouver Sun

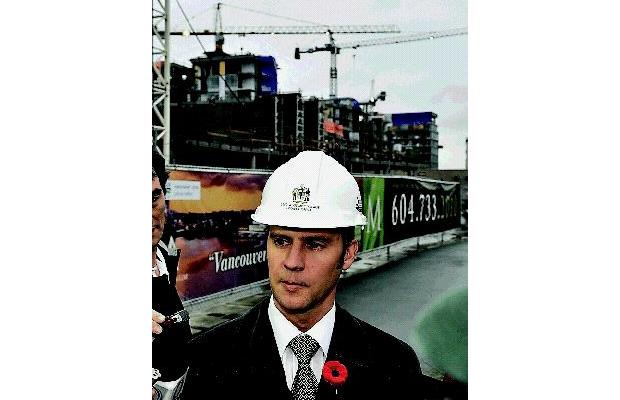

Former deputy city manager Jody Andrews, who resigned Thursday night, wrote a 12-page staff report recommending that city council select Millennium Properties Ltd.’s bid to develop the Olympic Athletes’ Village. Photograph by: Ian Lindsay, Vancouver Sun, Files, Vancouver Sun

The essential error that led to the Olympic Athletes’ Village debacle was made in April 2006, when city staff recommended that council select Millennium Properties Ltd. as the developer.

A 12-page staff report, authored by deputy city manager Jody Andrews, said Millennium’s proposal met or exceeded all the requirements of the official development plan.

The report also said Millennium had offered a “guaranteed, unconditional price” of $193 million for the 17-acre tract of city-owned land on False Creek, the highest of all bids, and did not require the city “to assume any of the marketing or financing risk in the development.”

But the report provided no details on how Millennium was going to finance the $750 million in projected construction costs. These details were crucial, because the city had given Vanoc — the Vancouver Organizing Committee for the 2010 Olympics — an undertaking that the project would be completed by November this year.

If the developer did not have a sound financing plan in place, there was a real risk that the project would stumble and the city would have to ride to the rescue.

This risk was heightened by the fact that ownership of the land would stay with the city. Millennium would make a $29-million deposit on the land, but title would remain with the city until the project was completed and the units sold. Then the developer would pay the balance of the purchase price and title would revert to the developer.

City staff said this made it a risk-free deal for the city. But without the land, the developer could not use it, or the improvements thereon, as security. The bottom line was that, without outside support, it was not a financeable deal.

These, however, were the halcyon days when debt capital was in abundant supply and condos were in huge demand. If any concerns were voiced, they were muted by the prevailing winds. Also, the clock was ticking. There wasn’t time to ask questions and wait for answers. City councillors unanimously approved Millennium as the developer.

It’s now clear that no firm financing arrangements were in place. It wasn’t until June 2007 that financing details emerged. City staff told council that Millennium was proposing to borrow the entire $750 million to finance construction. The only equity it had in the deal was the $29-million land deposit. This amounted to just three per cent of the nearly $1-billion total cost.

The problem with such a highly levered deal is that it leaves no room to breathe if there are cost overruns or the project gets hung up. Given that the city had given Vanoc an undertaking to complete the project on time, this was a risky deal not just for the developer, but also for the city.

So who’s going to finance such a risky venture? Certainly not a conventional bank. So Millennium turned to the rough-and-tumble world of hedge funds, which typically raise money from private investors for reinvestment in deals that are too gamy for mainstream banks.

In February 2006, CFO magazine reported that hedge funds “had become a key player in capital markets, specializing in high-risk loans to the financially distressed.”

“Hedge funds may charge borrowers interest rates of 14 per cent or more, double the rate banks charge their better corporate customers. Most borrowers don’t balk. That’s because the lightly regulated hedge funds are more willing to take chances on risky ventures and structure deals creatively.”

But the magazine warned that borrowers have reason to be wary, too: “Unlike banks, which presumably have a vested interest in their clients’ financial health, hedge funds may have other motives, such as profiting from a forced restructuring if the borrower falls behind on its loan.”

The hedge fund that Millennium was dealing with was New York-based Fortress Investment Group. It shared the breed’s reputation for ruthlessness.

“As real estate prices have skyrocketed in recent years, developers have gone to hedge funds like Fortress for the riskiest pieces of debt,” Fortune magazine reported in February 2008.

“These new, more opportunistic lenders charge interest rates that can rise above 20 per cent. If a developer defaults, some hedge funds are more than happy to grab their collateral and flip it for a potentially higher profit. This is referred to as the ‘loan to own’ business.”

In February 2007, Fortress became the first hedge fund to go public. Its initial public offering was priced at $18.50 per share. On the first day of trading its share price soared to $31. The firm was flush with cash and willing to take risks, but it balked at the Millennium deal. Not only was it being asked to provide 100 per cent of construction costs, the underlying property could not be pledged as security.

So in June 2007, city staff went back to city council, explained the dilemma and told councillors that, given the time constraints, the only choice they had was to provide Fortress with the security it required: a $190-million guarantee (in lieu of security over the land) and a guarantee that the project would be completed (so Fortress would have salable collateral at the end of the day.)

The “risk-free” deal had suddenly evaporated. Some councillors balked at providing the guarantees, but the NPA majority voted in favour.

I am quite sure that, if Millennium and Fortress had insisted on these terms in April 2006, city staff and council would have shown them the door and turned to Concord Pacific or Wall Financial, which had offered less for the land, but had more experience with large projects and better capacity to finance the project. But it was too late now.

By October 2008, Fortress had advanced $317 million, but its fortunes had sharply reversed. The credit crunch had constricted the supply of capital. Asset values were plunging. Redemptions were soaring and its stock price was plunging.

Millennium, meanwhile, had encountered a $125-million cost overrun, putting it offside with its lender. Fortress, already drowning in a liquidity crises, took the opportunity to cut off funding.

That was when council, clearly at the point of no return, agreed in a closed meeting to advance up to $100 million in interim funding. With Fortress still on the sidelines, the city has now asked the provincial government to amend the city charter to enable it to borrow the remaining $458 million required to complete the project. The legislature was expected to sit today to deal with the request.

So what’s the city’s exposure? Obviously that depends on the difference between the final cost (including all carrying charges and opportunity costs) and the selling price. Both are in a serious state of flux, so it’s anybody’s guess.

As security for the city’s advances, Millennium’s principals, Shahram and Peter Malek, have provided the city with a $250-million personal guarantee. Although councillors were assured that the Maleks‘ net worth is at least that much, asset values are plunging rapidly and, in any event, personal guarantees are notoriously problematic to enforce.

So Vancouver taxpayers are stuck in a kind of financial purgatory, the victims of politicians and bureaucrats who, despite the city’s stake in the outcome, failed to ensure sound financing was in place at the outset.

On Thursday, city manager Penny Ballem announced that Andrews had resigned. No reason was given.

© Copyright (c) The Vancouver Sun