… And what they must do to set it right

James Bagnall

Sun

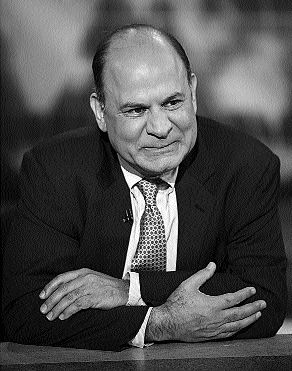

Liaquat Ahamed, author of Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World, finds comparisons with the Great Depression. Photograph by: Reuters, Canwest News Service

In September 2008, Liaquat Ahamed had just finished the manuscript for his first book, Lords of Finance.

He was 55, a former investment banker and economist with the World Bank. Ahamed had spent nearly a decade — the previous four years full time — studying the Great Depression through the eyes of the world’s top four central bankers.

It was history, obviously. But as Ahamed pulled together the various strands of research, he was struck by two simple, yet profound parallels with today’s economic mess.

The first was that the health of even very large economies depends on the actions of a small number of individuals. The central bankers of Britain, France, Germany and America in the late 1920s and early 1930s made decisions that unnecessarily consigned a generation to penury. There’s a distinct possibility that similar mistakes in policy could extend or deepen this year’s troubling economic contraction.

Ahamed’s second over-arching insight had to do with the fragility of the financial system itself. Since 1870, he learned, there have been more than 60 instances in which countries experienced at least a 15-per-cent drop in per capita GDP from peak to bottom. Many of these economic collapses resulted from failures of banks.

In the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, these financial spasms became fewer. Banks were tightly regulated institutions with a focus on taking deposits and lending money. Those deposits were insured, and the relationships between lenders and borrowers were clear and direct.

But Western financial markets seem predisposed to the formation of bubbles. It starts with what seems healthy optimism, which intensifies gradually into cockiness, then mania. The boom phase — in stocks, real estate or commodities — often stretches for years. Invariably it ends with a shock that seems to come out of the blue — at which point mania transforms overnight into panic.

Ahamed concludes that it is up to the small cabal of central bankers to stop bubbles from forming or, when that fails, to maintain faith in money.

“The goal of a central bank in a financial crisis is both very simple and very elusive,” Ahamed notes, “to re-establish trust in banks.”

Ahamed grew increasingly disturbed in the 1980s and 1990s by the frequency with which this trust was violated. There were currency meltdowns in Mexico, Asia, Russia and Latin America. Ahamed puzzled over many instances of failed financial institutions — from U.S. savings & loans firms to hedge funds.

“These crises had become endemic to capitalism,” Ahamed says. “So I began reading up on the mother of all crises, the Great Depression.”

Ahamed had completed most of his manuscript by August 2007, when the context for his book began to change dramatically.

BNP Paribas suspended withdrawals from three of its investment funds, which held financial products based on the health of America‘s mortgage industry. Later, the industry would come to see the BNP Paribas suspensions as the start of the great global credit crunch. Not at the time, though.

“Never in my wildest imagination did I think [US. mortgage] loans would threaten the whole Western financial system,” Ahamed says. His thinking, and that of many others, underwent an epiphany on Sept. 15, 2008, when Lehman Brothers, a mid-sized investment bank, filed for bankruptcy. This apocalyptic event ushered in an era of fear that has yet to abate. Ahamed likens it to the 1931 failure of the Credit Anstalt, the largest bank in Austria.

Like Lehman Brothers, the Austrian bank had invested directly in industry — borrowing short-term money to finance longer-term, riskier investments. Adding to the potential danger, Credit Anstalt’s balance sheet was stuffed with foreign borrowing. The bank’s failure prompted a run on all Austrian banks, creating a contagion of fear that destroyed financial institutions around the globe and extended the Great Depression for at least another two years.

Austria‘s experience in 1931 was very fresh in Ahamed’s mind last September, when former U.S. Treasury Secretary and Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke declined to rescue Lehman Brothers. “It was astounding what a shock to the system it was and how much panic it caused,” Ahamed said. “Much more than anyone realized.”

Obviously a great deal more than either Henry Paulson or Bernanke had contemplated. For the past six months, top financial officials have moved aggressively to counter the loss of confidence in financial institutions. The effort continues today in Britain. Finance ministers from the world’s top 20 economies will try to agree on Saturday on a plan for infusing economies with enough liquidity to reverse the slide.

“I believe we have avoided another Great Depression,” says Ahamed. “In the 1930s the central bankers gave the patient the wrong medicine. Today we know what medicines to give, we just may not be giving high enough doses.”

Eighty years ago, the prevailing wisdom was that economies should be anchored by gold — the idea that paper money should be convertible into gold wherever people travelled and did business. The system was incredibly precise, and rigid. The British pound was worth 113 grains of pure gold while the U.S. dollar was valued at 23.22 grains. This meant the pound was worth exactly $4.86 as long as both countries agreed to back their currencies with the precious metal.

But Ahamed points out that imbalances in the supply of gold — with Britain and Germany relatively short of the stuff, and France and the U.S. holding generous quantities — proved unhealthy. Britain, for instance, was forced in the 1920s to keep interest rates high in order to keep gold supplies from dropping.

At the same time, the U.S. held its interest rates low. This action contributed to the 1920s stock boom in much the same way that Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan’s low interest rate policy helped to inflate Internet stocks in the 1990s, then housing prices after 2001.

In 1929, the real damage done by adherence to the gold standard was simply this: It prevented governments from implementing new spending that might have helped to offset the damage done by a contracting world economy.

Ahamed maintains that the beginning of the end for the Great Depression came as soon as countries took themselves off the gold standard. Britain made the break in 1931 and the U.S. and Canada followed suit.

The trouble was, these moves came only after years of exceptionally painful economic contraction. The value of America‘s gross domestic product slumped 26.5 per cent from 1929 to 1933; in Canada, the fall in economic output was an even deeper 27.7 per cent. From these depths, it required another half decade of real economic growth to return to the levels of 1929. However, the hard lesson that financial systems require determined oversight by central bankers or regulators did not take hold.

This much became clear as Greenspan and other central bankers allowed housing markets, and related financial products, to gather phenomenal heft.

Governments were unwilling to regulate the emergence of a virulent new financial industry — what became known as the shadow banking system. Investment banks, hedge funds and other unregulated institutions grew rapidly, fuelled by sales of financial products that depended on rising house prices and a healthy flow of mortgage payments.

Paul Krugman, winner of the 2008 Nobel Prize for economics, frames the danger succinctly in The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008. “The crisis hasn’t involved problems with deregulated institutions that took new risks,” he wrote. “Instead, it involved risks taken by institutions that were never regulated in the first place.”

The shadow banking system, in other words. The fact that so many of these mortgage products were not insured contributed heavily to the panic of last September.

And so, the credit crisis leaked with surprising force from the financial sector into the regular economy. The assets attributed to the shadow banking sector plummeted, along with the value of the mortgages that underpinned them. Hundreds of billions of dollars were sucked out of the economy as the sector shrank. Regular banks — deposit-taking institutions such as Wells Fargo — could not make up the difference. The next stage came quickly. Regular businesses — manufacturers, retailers — were either starved of capital or cautiously shelved plans to expand.

Central bankers now are trying desperately to arrest their economies’ downward momentum.

Canada‘s $1.6-trillion economy contracted 0.8 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2008 (in real terms, after inflation, compared with annualized GDP in the third quarter). The consensus is that the rate of decline in GDP will pick up slightly in the first quarter of 2009, then gradually diminish.

A return to growth by the second half of this year is considered likely.

© Copyright (c) The Vancouver Sun