Residents will interact as an environmentally friendly community, rather than exist in isolation inside the towers

DERRICK PENNER

Sun

The Millennium Water development on the south bank of False Creek, which will serve as the Vancouver Olympic athletes village, has raised the bar for future eco-friendly residential developments

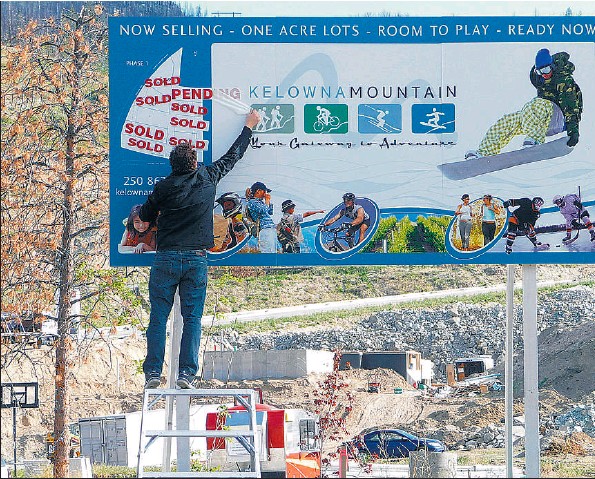

Ian Mayall checks the overhead blue channels of the heating/cooling system during a tour of the Vancouver 2010 Olympic Village to see its environmentally sustainable features. IAN LINDSAY/VANCOUVER SUN

The Millennium Water development on the south bank of False Creek, the 1,100-unit housing project that will serve as Vancouver’s Olympic athletes’ village, will certainly be environmentally sustainable, design manager Roger Bayley assures visitors.

A so-called district energy system will sop up residual heat from city sewer pipes to warm water feeding the vein-like capillaries in the development’s ceiling-mounted radiant heating system. (In the summer, those same capillary-mat panels can reverse, running cool water, to draw the heat out of homes.)

Buildings in the development will feature wider, naturally lit and ventilated corridors and thicker, more deeply insulated exterior walls, and exterior, automatic shading to keep units naturally cool in strong sunshine.

Unseen, drains will siphon rainwater falling on the project’s buildings into basement cisterns that will irrigate its copious green roofs and gardens in the summer and be enough to flush its toilets in the fall and winter.

However, beyond those features, which will combine to reduce Millennium Water’s energy use by 50 per cent and potable water use by 40 per cent (compared with its neighbours on the north side of False Creek), Bayley takes his visitors to the internal courtyard of the site’s Parcel 10 as the best vantage point to paint a picture of its overall sustainability.

Parcel 10 is still only dusty concrete, but here Bayley, with the firm Merrick Architecture, the planning firm for developer Millennium Development Corp., layers on images of what it will become.

Verdant gardens will be added, he said, including evaporative rainwater ponds that will act both to irrigate the shrubs and plants and cool the air on currents as they flow around gaps in the buildings designed to take advantage of air movement.

The courtyard is a perfect vantage point, Bayley said, to look up at the windows of the homes under construction, their proximity and how they all look out on this common space where neighbours can interact as a community rather than exist in isolation inside the towers.

“A lot of people think of sustainability in environmental terms only,” Bayley said during a recent tour of the construction site.

“They don’t think to take the next step of the social issue and what the social circumstance [of the development] feels like, and how those inter-relationships work.”

Notwithstanding Millennium Water’s environmentally sensitive features, that sense of community arising from residents’ ability to interact is a big element of what it means for a housing development to be sustainable.

Nor will it be just a sense of community among purchasers of the 736 market-priced homes in Millennium Water, but also among the residents of the 253 subsidized housing units and 119 rental apartments across the site, and how they will use the public spaces of the central plaza and the waterfront walkway.

“I think that’s the big experiment here,” Bayley said.

“This intermingling of different social activities and different social structures is all going to play out here in a melting pot that I think a lot of people are going to watch and see how successful it really was.”

Four main architect groups designed the project, including the late Arthur Erickson with collaborator Nick Milkovich, Stuart Lyon at GBL Architects Group Inc., Walter Frankl and Merrick, which designed the main buildings of the Olympic Village and coordinated the design team.

Hank Jasper, with the project’s developer, Millennium Development Corp., calls the design “civilized living in urban spaces.”

“I don’t want to sound like too much of an urban planner,” Jasper, general manager of construction and development for Millennium, added in an interview, “but that’s effectively what [the developer] has become, because it is a partnership between the city, us and the community.”

Some of the challenges that city officials had to co-operate on to meet the project’s objectives included allowing the developer more floor area in its buildings than usual in exchange for constructing thicker, more deeply insulated walls to meet energy conservation goals and wider corridors and stairwells to allow for the flow of natural light and ventilation.

“It’s a learning curve for everybody,” Jasper said, but a valuable lesson for everyone — from the city’s planning and building offices, to Millennium, to the consortium of architects to main contractors ITC and Metrocan and all their subcontractors.

“ We figured out ways to do things, and creative ways to do things, so I think it turned out to be very successful,” Jasper added.

One example: The project’s tight timeline (Millennium had just 30 months to turn the site from bare brownfield into more than a million square feet of built space) required the designers and contractors to make detailed layouts of all the suites sooner than they normally would to accommodate the manufacturing of the capillary mats for the radiant heating system.

The layout of ductwork for a typical condominium is “not that exacting,” Jasper said. Builders usually have some leeway to adjust ducts around building features once the rooms are all framed in.

The capillary mats, manufactured by the German firm Beakers, had to be produced long before the rooms even existed in order for them to be shipped in time for installation.

So it was the detailed drawings for the capillary mats that dictated the framing of rooms and the placement of lighting fixtures and sprinkler heads because they wouldn’t be able to work the mats around anything once they arrived.

The result for residents who move in, however, will be a more comfortable, healthier, naturally ventilated building that isn’t sucking in massive amounts of outside air that has to be filtered, then heated or cooled, to be run through a forced-air heating system.

Jasper said he and Bayley have travelled to Germany and experienced how the radiant system works in buildings where it has been installed.

“It has an overall much more comfortable feel.”

The City of Vancouver’s overall objective was to turn southeast False Creek, where it owned a substantial portion of the land, into a showpiece for sustainable development.

Millennium secured the rights to develop the city’s portion of the land, with a $193-million bid, to build about one million square feet of residential housing and 70,000 square feet of commercial space.

Jasper said it was in the process of deciding just what “sustainability” would mean: a neighbourhood built to the Canada Green Building Council LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) gold standard.

That included designing a community centre to LEED platinum standards, and throwing in a so-called “net-zero” apartment complex, which will create more energy, through systems such as a solar heating system, than it uses.

Jasper admitted the green features did add costs to the project. His estimate is about seven per cent over more typical construction methods.

However, the systems, in their totality, create value for residents in the quality of life that the development offers.

For Millennium, the payoff is that at a time when there is more focus on creating buildings that are friendlier to the environment, they are now at the leading edge of delivering that product in residential housing.

“We have a couple of projects on the board where we’re going to pursue similar LEED standards,” Jasper said.

“I’m not going to say we’ll do every project this way, but for certain projects and high-profile projects like this, I think the future buyer, they’re making a lifestyle choice,” Jasper said. “And I guess we’d like to think we’re in the forefront of delivering on that kind of lifestyle.”

It is certainly a lifestyle that the City of Vancouver hopes will catch on for future developments.

The fact that Millennium is already looking for ways to use what it has learned about sustainability in other developments is one thing that Ian Smith, development manager of the southeast False Creek and Olympic Village project for the City of Vancouver, counts as a success.

In 1997, Smith was the city planner overseeing official community planning for the cityowned lands when they started with the simple, vague notion of making “a model for urban sustainability.”

“We started out with an official development plan,” Smith said, “and shortly after, we won the Olympic bid to make it happen.”

Smith credits that event’s fixed timeline as an advantage to focus everyone’s attention on being decisive.

“ One of the real dangers in dealing with sustainability is that everybody loves to talk about it,” Smith said. “And there is always some kind of hope that next week there will be some new answer in Germany or Sweden that is going to be more sustainable than anything we’ve ever seen.”

However, Smith said the results so far have been better than expected in terms of the amenities that the city has gained, from the waterfront walkways and parks, to the construction of the district energy system and the legacy of influence that the planning effort to create the Olympic Village has already had around the city.

Smith said a lot of what has been learned “is being transferred to other buildings in the city. It continues to influence the way we do business.”