Is cramming more people into the existing space the answer?

Carmen Chai

Province

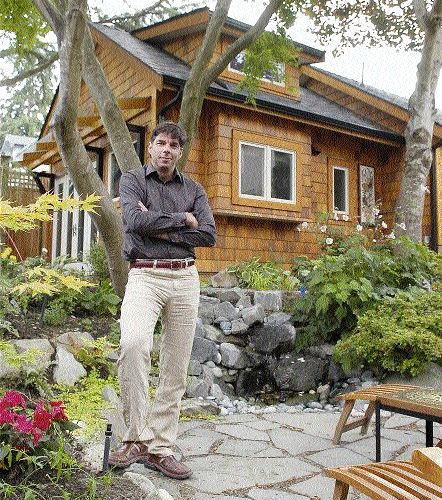

Jake Fry, president of a company that builds laneway houses, stands in front of one of his creations.;He predicts the demand for such coach houses will undergo steady growth. Photograph by: Arlen Redekop, The Province

Clark Kim, a student from South Korea, lives in half of a living room in this building. Photograph by: Arlen Redekop, The Province

The city calls them affordable housing options that will provide more choice for hard-pressed renters.

Skeptical renters? They call them “mouse holes.” They say the city is creating a cluster of tiny, ill-thought-out housing that will pack too many people into areas with too few of the amenities that make neighbourhoods livable.

Only time will tell who’s right.

As Vancouver challenges Manhattan for its reputation as a renter’s nightmare, the city is about to allow laneway homes, more and bigger basement suites, even tiny secondary suites tucked into existing rental apartments and condo suites.

Debate has been heated and council chambers packed as council discusses the bylaw changes that it hopes will lead to more, and more affordable, housing.

The city has made it clear change is coming, and virtually everyone agrees it’s needed.

Ads circulating online give a hint at the desperate situation renters face now, as even those lucky enough to find space hustle to pay for it.

“We have a nice LIVING ROOM space for rent in our apartment,” read one brutally direct ad on Craigslist on July 19.

“What are you going to find in this living-room space? A hanger where you can fit your clothes, a metallic shelf to organize your stuff, a single-sized bed and a little wooden table. The window view is facing downtown beach side. $350 a month. Davie and Bute.” The ad, just one among many, indicates that the living room is no longer just a household’s traditional meeting point.

In the Vancouver housing market, it has become a commodity in the marketplace of renters.

The shortage is a simple equation, says Brent Toderian, the city’s director of planning.

As the supply of available rental housing diminishes, the price of ownership and renting increase.

“Over half the residents in Vancouver are renters and in any expensive city having a rental stock is critical to sustainability, economic development and affordable housing,” he says.

“When prices are as high as they are, there is a push on space and people get pretty creative.” Clark Kim, a South Korean international student, knows all about creativity. He’s been sharing a living-room space since January.

Kim sleeps in the partitioned-off living room of a two-bedroom West Georgia Street apartment. Another student sleeps on the sofa bed beside his.

“I like it because it saves me money every month,” Kim said. He pays $455 a month for the fully furnished living room, which comes with wireless Internet.

“Maybe it’s because I’m a guy, but not having so much privacy doesn’t bother me.” Kim chose the shared space because of the price, the location and because he could practise his English with Canadian roommates.

“It’s good here. It’s a nice place,” he says.

The apartment is elegant, with hardwood floors, floor-to-ceiling windows and a balcony with an impressive view.

But with just a dresser and two sofa beds in the corners of the living room, it’s also spartan.

Still, a living situation like Kim’s may be the solution to meet demands on Vancouver‘s scarce accommodation.

“This is just what the market is offering,” says Tom Durning of the Tenant Resource and Advisory Centre.

“We’re becoming like Tokyo, London and New York City. We’ve got to start looking at more density in all neighbourhoods,” Durning says.

He’s heard it all — half a dozen people living in a Richmond bedroom, owners renting out garages, houses carved into six units when they are only zoned for two.

“The city can’t police all of this. Residents are risking safety to find affordable living. At least secondary suites would offer more privacy and safety,” Durning says.

Vancouver and Victoria were the only cities in the province that had vacancy rates below two per cent, according to a spring 2009 Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. rental-market survey.

Vancouver‘s vacancy rate is now 1.9 per cent, an increase from 2008’s 0.9 per cent, but still a far cry from the three to four per cent that’s considered healthy for the market.

The city also had the highest average monthly rent in the country for a two-bedroom apartment in either new or existing structures.

The average monthly rent in Vancouver is $1,154, an $80 increase from what renters were paying in 2008.

“Clearly, now is the time that we need to be innovative. Anything that will take the pressure off needs to be done,” Durning says.

But the city’s answer to “innovative” is getting mixed reviews.

Durning calls the bylaw changes an “evolutionary good move” that will protect renters who need affordable housing. He says the secondary suites within apartments will offer students, seniors and low-income residents housing options.

Alicia Barsallo, organizer of the Coalition Against EcoDensity and For Livability, disagrees.

“They’re just terrible ideas,” Barsallo says, pointing to both the secondary suites and proposed laneway homes.

“Once you start this, it’s going to spread — and we’re going to end up like Tokyo, where people get used to living in tiny spaces. And that lowers the standard of living of our city,” she says.

Barsallo calls the secondary suites “mouse holes.” She argues that laneway homes will clutter Vancouver backyards.

And she’s angry that city council is “densifying without provision for anything else.” Her coalition, which has had as many as 60 members at most meetings, is concerned about the repercussions of the rushed decisions it says the city is making.

“They’re creating space without increasing necessary amenities like health-care facilities, pools, community centres and green areas,” Barsallo says. “We can’t ignore that the government is not creating spacious, affordable housing.” Toderian said the increase in supply will be a “gentle form of gentrification” and that critics who compare Vancouver with crowded cities are exaggerating.

He said secondary suites and laneway homes will create “invisible and hidden density.” In the city’s defence, Toderian notes that apartment secondary suites may not be available for some time.

“The costs make it very difficult to retrofit existing buildings. We’re anticipating that it will largely be a new opportunity for new construction,” he says.

But laneway homes and basement suites are economical options now, he insists.

Toderian even argues that building a basement suite or a laneway home during the economic downturn would be a wise investment, because construction costs are lower and rental rates are high now.

“It’s a simple thing ordinary homeowners can do as opposed to developers who can be strongly affected by the market and the economy.” Jake Fry, owner of Smallworks, a local company that designs laneway homes, says he’s built about 24 studios in the last three years.

Fry is anticipating a slow, steady, one-per-cent increase in business per year.

“It will be modest in its uptake. You’re going to see a few dozen go up right away,” Fry says.

“But there will be an initial rush with families who need them for aging parents or extended family.”

© Copyright (c) The Province