It is easy to fall into the habit of ignoring the real world when you are always plugged in

Gillian Shaw

Sun

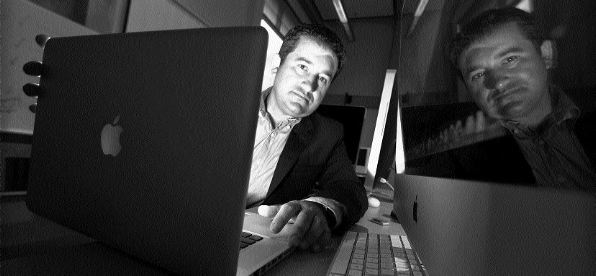

Alfred Hermida, who leads the integrated journalism program at the University of B.C.’s School of Journalism, utilizes all available technology in his daily life but still tries to take some time off. Photograph by: Ward Perrin, Vancouver Sun

Marc-David Seidel was sitting in a cafe in Berkeley, Calif. watching two customers at a nearby table carry on an awkward and disjointed conversation that made it clear each was more concerned with eyeing their phones lying on the table.

While the pair were together in person, their attention was directed to cyber conversations instead and it was only when a thief snatched both phones off the table as he ran by that the two focused on each other.

“They were having a very disjointed conversation — I couldn’t help but notice — it was like two monologues,” said Seidel, associate professor in the University of B.C.’s Sauder School of Business, who has done research on social networks and has been online since 1980.

“Until somebody ran by and grabbed both their phones and then they started interacting with each other for real — they had a conversation about crime.

“It was a perfect metaphor for our digital life.”

LINES ARE BLURRED

It’s a life that has become 24/7, where the lines between work and leisure life are becoming so blurred that it’s projected they’ll disappear totally by 2020.

When the Internet first emerged, it effectively had an off switch. You had to go through a tedious process of logging on, logging off, and waiting while traffic wended its way through the clunky connections of cyberspace. Today, you can carry a virtual computer in your pocket in the form of your iPhone, BlackBerry or other smartphone and you can be constantly cyber-connected.

If people can’t call you on a land line, a cellphone, a satellite phone — there’s always text messages, Facebook, Twitter messages, LinkedIn, e-mail, your Flickr site that shares your vacation photos while you’re still on holiday and online games that let you compete with people around the globe and around the clock.

For some, it’s so ubiquitous that failure to answer an e-mail or a tweet for a day or so can have friends, relatives and colleagues speculating that the recipient has met some awful fate.

Going off the grid doesn’t necessarily mean disconnecting — you could be sitting around a campfire watching YouTube videos on your iPhone, or as one vacationing dad did — sending minute-by-minute photos of a European vacation with family — leaving viewers to wonder if the man was devoting any attention to his family or merely documenting their travels.

“It used to be a healthy divide, but the 24-hour reach of technology puts an end to the separation between work and private life; it blurs the boundaries entirely,” said Seidel. “That can be both positive and negative.”

Seidel’s research has left him convinced that online social networks lack the quality of face-to-face interaction and even phone calls and written letters. And he says people overestimate their ability to multi-task — a contention he regularly proves in his class by calling on students who are intently staring at their notebook computers. The ones who are using their computers to take notes are quick with an answer; the ones who are checking out Facebook answer with a blank look.

“I would say online social networks don’t really replicate offline social networks,” said Seidel. “They tend to be surface rather than deep and meaningful connection.”

The 24-hour connectivity sets up expectations both in work and personal life.

“If you don’t respond instantly people think something is wrong or that you are ignoring them,” said Seidel, who, despite having worked with the Internet since 1985 refuses to carry a BlackBerry or a smartphone and only carries a laptop when he is travelling. Right now he is on sabbatical and he has set his e-mail to auto reply telling senders he isn’t available until July of next year.

“I have figured out how to manage,” he said. “I am old-fashioned, the Internet for me is something that should be there when I want it to be, it shouldn’t be able to grab me.”

Alfred Hermida, a colleague at the university and a professor who leads the integrated journalism program at UBC’s graduate school of journalism, grapples with such issues both in his own life as a “digital news pioneer” and in teaching a generation of students that takes the Internet for granted — regarding it not as an adjunct to their life but as an integral part of it.

I sent Hermida a direct message on Twitter asking if he was available for an interview, knowing because he is on my Twitter network that my message would be reaching him in Toronto.

Hermida also has a blog at http://reportr.net, a website www.alfredhermida.com, he runs www.newslab.ca , has a Flickr account for photos and video, an online video show, JournalismPlus.com on Blip.tv, he is on Twitter, on LinkedIn, Facebook, YouTube, Ning and several other social networks.

Hermida answered my message on his iPod touch and we talked over the phone.

GENERATIONAL OUTLOOK

“It is very much a generational outlook,” Hermida said of the notion that technology is something to be turned off or on in our lives. “For the freshman class at university, it is not a case of taking over their lives, it is part of their lives.

“The whole idea of contemplating a world before the Internet is very alien to them. One of the things with technology is that if it is part of the way you live, it becomes invisible.

“You don’t really think you are using a device for something. Just as you don’t say, ‘I need to set aside time to use the telephone.'”

Hermida doesn’t segment technology into working tools and devices for leisure. The same iPod touch that allowed me to connect with him was also helping him find his way around Toronto using Google maps.

“In a sense, technology becomes a part of what you do,” he said. “You don’t think about it in terms of setting aside time for it.”

Hermida sometimes asks his students go offline, a task they can find daunting.

“Sometimes I ask my students to go offline for eight hours and often it is a bit of an eye-opener,” he said. “After about half an hour, they are saying, ‘what do I do now?’

“Or they will go and take a walk and they won’t be plugged into an iPod — they’ll hear birds chirping in the trees and they’ve never heard that while they’re walking.”

While Hermida is a digital pioneer, he sets limits — managing expectations of students he says have grown up expecting and getting instant feedback.

“Their expectation when they e-mail is that you will reply straightaway. I’ll say, ‘I’ll get back to you within 24 hours.’ Maybe it’s the evening and I want to have some time off.”

Hermida doesn’t decide when to connect digitally — it’s the way he lives.

“I have to make a conscious decision to disconnect,” he said. “It is not a conscious decision to connect — my default state is always on.”

Hermida will get a head start on catching up with e-mail by checking in Sunday night, a practice he says friends do as well.

“It is almost because you can, you will,” he said. “The responsibility then falls to individuals to make those limits — to say, ‘if you e-mail me over the weekend I’ll get back to you Monday.'”

Answering the boss’s call or e-mail on your BlackBerry is one of the many ways the line between work and leisure is disappearing. According to a forecast by the Pew Internet & American Life Project, by 2020 that line will have disappeared.

Jonathan Ezor, assistant professor of law and technology and director of the Institute for Business, Law and Technology at the Touro Law Center, and special counsel to The Lustigman Firm in New York, said that raises a number of issues for both employees and employers alike.

“There are a few things employers have to be concerned about. One has to do with work hours; to the extent that employees need to track their hours and making sure policies are very clear as to what constitutes work.

“Is being on one’s Palm Pre at the beach work hours? And how does it get tracked?”

On the flip side, someone in an office cubicle could be betting on a sports event online, planning a party, holiday shopping or catching up on Facebook. Ezor points out that for both sides in the employment equation, technology brings advantages and disadvantages.

Security is another consideration when people are able to work anywhere anytime and laptops and smartphones can carry enough data to pose a substantial risk to companies and organizations if they are lost or stolen.

“I look at this from the point of view of a technology lawyer as well as technology fan,” said Ezor, who also has a website, www.mobilerisk.com.

BALANCED SCHEDULE

For Ezor, technology helps balance a complicated schedule that includes a full-time position as a professor, consulting work as a lawyer and parenting children with special needs.

“That is the benefit side, you can work whenever you need to, on your own schedule — you can be productive and you can take a family trip even if there is some critical piece of information you might be asked for,” he said.

“But we are working more hours than we used to. You can no longer say, ‘Sorry, I can’t be reached.’ It is very hard to be off the grid these days — you have to make a serious effort to be unreachable and that is a downside.

“Today if you’re a mechanic you’re not fixing cars by BlackBerry. For information workers to be able to work wherever one wants it can be a wonderful thing. To have to work wherever one is — that can be good or bad.”

David Gewirtz, editor-in-chief of ZATZ and cyberterrorism adviser to the International Association for Counterterrorism and Security Professionals, recently released a special report entitled The Dark Side of Social Networking.

Gewirtz focuses on the security implications of social networking sites such as Facebook, Twitter, MySpace and LinkedIn. But with more than two-thirds of the world’s Internet population visiting such sites at least once a month and nearly 10 per cent of all time spent online devoted to social networking, he also sees the life balance issues in technology.

“I’m addicted to e-mail so I check it before I have my first cup of coffee and last thing before going to bed,” he said. “I used to drive across the country without a cellphone; now I’m not willing to drive around the corner to the 7-Eleven without making sure I have my cellphone and that it is fully charged.”

Gewirtz has 15 to 20 computers in his house and he talks about a three-day vacation he once took in British Columbia as a memorable holiday.

“I claim to my wife in a perfect world I’d never touch computers again, I’d never use e-mail and I’d be as happy as a clam,” he said.

“Until I want to order something from Amazon.”

With information and entertainment coming at us from numerous sources and at a pace that can quickly overrun our schedules, many people don’t think of just doing nothing.

“My TiVo has 2,000 hours of programming — every one is something either I or my wife wants to watch,” said Gewirtz. “You can keep yourself entertained any time of the day or night.”

Despite his compulsion to check e-mail, Gewirtz has one unbreakable rule — he doesn’t give out his cellphone number.

“If I’m out, I don’t want to be disturbed,” he said. “I used to find the cellphone chasing me everywhere I went.

“Customers and contacts are annoyed when they can’t find me on a cellphone, but I really prefer not to scream over a concert to a customer.

“Those are the boundaries we need to set up digitally. The real answer is good living practice.”

Justin Young, managing director of Radar DBB, a marketing and branding company that is deep into Web 2.0, said when you spend all your time online, it is hard to differentiate what is work and what is play.

The answer, he said, is deciding what specific hours are for — for example, if he is working on a presentation, he’ll turn off his e-mail.

“Technology,” he said. “It can run you or you can run it.”

© Copyright (c) The Vancouver Sun