Drew McLauchlan

Van. Courier

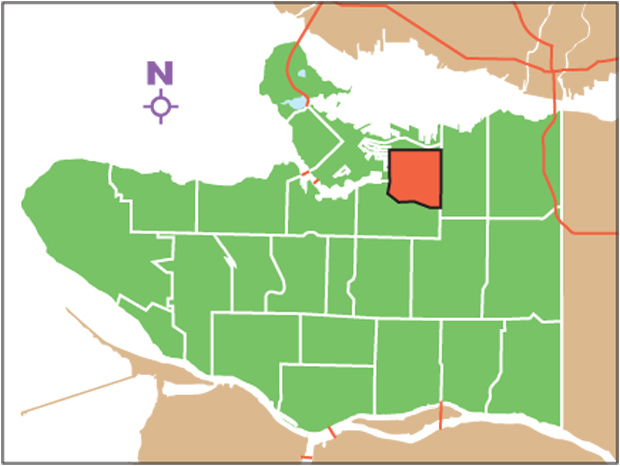

Strathcona neighbourhood in Vancouver, British Columbia Photograph by: Vancouver Courier , file.

As Vancouver’s oldest residential neighbourhood, Strathcona has a long and rich history that is stained with soot, fire and grinding poverty. Despite plots of gentrification, however, its residents have always held on to the working class soul of the community.

Strathcona is bordered by Burrard Inlet to the north, Clark Drive to the east, False Creek to the south, and Chinatown to the west. Before European settlement, the Squamish, Musqueam, and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations people occupied the area. Strathcona began as a camp of cabins built around Stamp’s Mill (later renamed Hastings Sawmill.) The early neighbourhood served as a hub for labourers migrating from across the country, China, the U.S. and Europe, who were drawn to Canada’s western frontier.

As a result of the mass influx of workers and their families, Strathcona was the location of Vancouver’s first school: Hastings Mill School, a single-room schoolhouse that also served the children of Moodyville (now North Vancouver.) The Hastings Sawmill was one of the few structures to survive the Great Vancouver Fire of June 1886 and its unlikely survival would later reflect the perseverance of Strathcona’s heritage throughout the next century.

Strathcona takes its name from Lord Strathcona (Sir Donald A. Smith,) who drove the last spike completing the first transcontinental railway at Craigellachie, B.C.

During the 1960s, Strathcona was considered a slum by many. City planners considered demolishing a large portion of the neighbourhood to make room for an interurban freeway that would have also affected much of Gastown and Chinatown. The first part of the freeway, the Georgia Viaduct, was completed and effectively destroyed a section of Strathcona called Hogan’s Alley. Hogan’s Alley was Vancouver’s predominantly black neighbourhood. The rest of the freeway never became a reality.

Though many treat the neighbourhood as a temporary home before moving to other areas of the city, a sense of pride and activism remains. On April 1, 200 residents protested what they saw as a hastily made plan by the city to remove the viaduct. The result, they say, would be an increase in traffic and congestion in Strathcona, which remains one of the few affordable options for real estate in Vancouver.

© Copyright (c) Vancouver Courier