?THEY THOUGHT I WAS GOING TO BACK DOWN and LEAVE?

John Colebourn

The Province

Jack Gates in his room at the Regent Hotel in the Downtown Eastside, where he complained last November about the lack of heating and hot water. MARK VAN MANEN/PNG

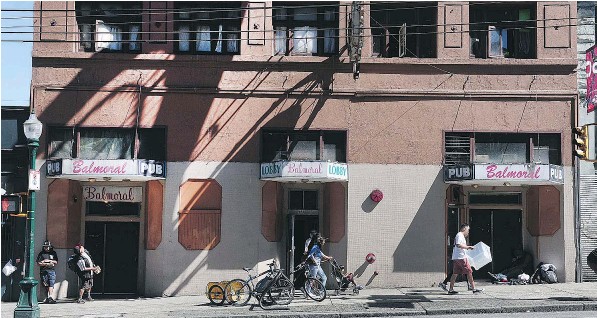

The Balmoral Hotel on East Hastings Street, which the Sahotas have owned for decades. Last month, a rotten beam snapped in the hotel?s basement, causing extensive damage to the bar above it. NICK PROCAYLO PHOTOS/PNG

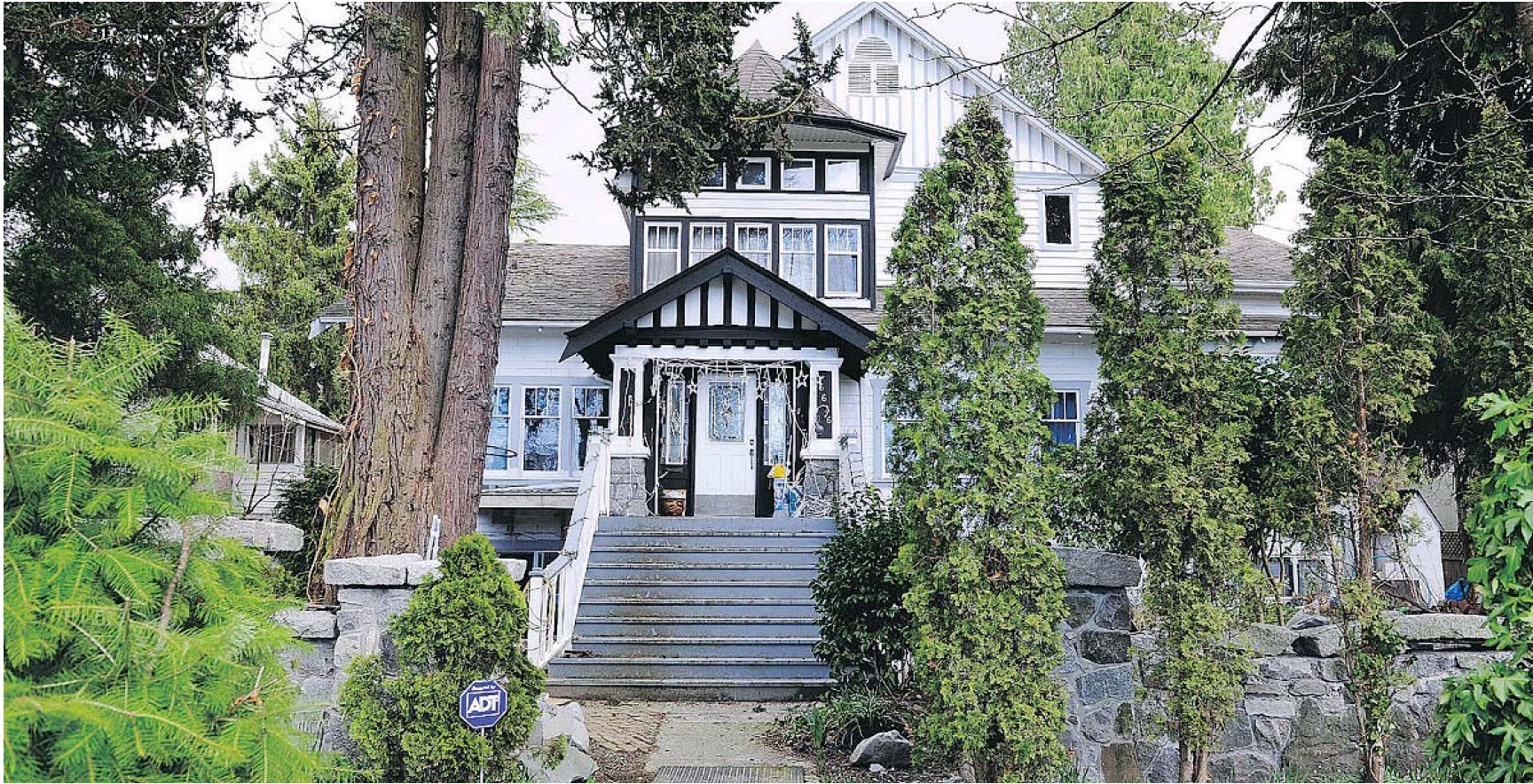

A house on Angus Drive in Vancouver owned by Gurdyal Singh Sahota

A recovering drug addict is standing up to his multi-millionaire landlord in small-claims court.

The case of Jack Gates versus Triville Enterprises Ltd. provides a glimpse into the real estate operations of the Sahota siblings, who have owned rundown rooming houses on Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside for decades.

Gates never thought he would have the fight of his life to get heat and hot water in his tiny room at the Regent Hotel.

He complained publicly about the lack of heat last November, when Vancouver was hit with a bitter cold snap that left him feeling like he was living inside a meat cooler.

He hoped his landlord at the East Hastings Street hotel would quickly address his complaints when his frosty tale became a local media event.

But it soon became apparent heat and hot water were a low priority — even though his disability cheque covering the monthly rent of $450 is paid on time to Triville Enterprises, a company whose sole director identified in public corporate records is Parkash Sahota.

Pal, 77, his brother Gudy, 79, sister Parkash, 86, and other Sahotas are listed individually or in different combinations in property records that show real estate holdings worth more than $130 million, according to B.C. Assessment property records.

In addition to running the dilapidated Regent, the Sahotas have for decades owned other Downtown Eastside single room occupancy (SRO) hotels, including the Balmoral, the Astoria, the Cobalt and The Regal.

Gates said when he moved into the Regent in 2014, his second-floor room was filthy. “I had to clean the room out. There were two mattresses in there and they were full of bed bugs,” he said.

A recovering drug addict, Gates, 54, has been clean and sober for almost three years but suffers from arthritis.

The cold conditions in his room this winter compounded his condition, he

On Jan. 18, 2016, Gates submitted a nine-page document to the province’s Residential Tenancy Branch outlining in detail his issues at the In his submissions, Gates said when he complained about the lack of heat, he was given a space heater — but it didn’t work as it tripped the power circuit to his room.

In his evidence package to the RTB, Gates said: “In September 2014, tenant moved into the Regent Hotel. He complained immediately to the front desk management staff that he had no heat and hot water … Tenant complained verbally a few times afterwards, but did not get any results … He was nervous about complaining too much out of fear of eviction and knowing there are no other rooms to rent in the area.”

Submissions were made by both sides. Arbitrator P.L. Senay said: “The agent for the landlord stated that the reason the circuit breaker is tripping in the rental unit is because the Tenant is using a refrigerator and a hot plate, which are not authorized.”

The RTB came to a decision April 1. Senay agreed that the basic necessities of heat and hot water should be provided with the monthly rent payment. Gates was awarded $1,425 for lack of heat and another $250 for the hot water problem, for a total of $1,675 in a ruling against landlord Pal Sahota and Triville.

“The landlord has never offered to relocate him as a result of inadequate heat … and the landlord has never offered to reduce his rent as a result of inadequate heat,” Senay said in the RTB decision.

Senay determined that Gates and others had complained for months to the front desk about the heat and hot water problems, and also found those who complained felt intimidated by the hotel manager.

“As a result (they) were discouraged from insisting that repairs be made … I therefore find it reasonable that the tenant stopped reporting problems to the front desk and eventually reported deficiencies directly to the city,” Senay said.

Despite the RTB win, Sahota — whose owner address with BC Assessment is a Shaughnessy house assessed at $3.7 million — has yet to pay. A warrant was issued because Sahota failed to show up to a mandatory payment hearing. He subsequently did appear and the arrest warrant was cancelled. Gates and Sahota are to appear again in small claims court on Aug. 16.

“They thought I was going to back down and leave but I wasn’t going to do that,” Gates said after court. “They treat tenants like they are not people. And that is not right.

“There may be more backlash with my case,” he responded when asked about his future at the Regent Hotel.

A week after his appearance in court, Gates was sent a notice that he was being evicted from the Regent. According to the notice, he has 30 days to leave.

Pal Sahota has been dealing with serious structural problems at the Balmoral Hotel, a cornerstone of his family’s vast real estate empire.

Located at 159 East Hastings, the Balmoral is home to 168 tenants, most of whom are on income assistance and the government-subsidized rent of around $450 a month is generally paid directly to the owners.

Lately, the ramshackle hotel built in 1908 has been showing its age. In early June, a large, rotten structural beam running across the entire basement ceiling snapped.

The mould-encrusted beam had had water steadily dripping on it for decades. When it broke, it caused the tiled bar-room dance floor above it to develop a two-foot dip. The serving station at the bar came off its moorings and the ceiling partially collapsed as the structure shifted.

It was feared at the time that the floor would collapse into the basement. On June 8, the City of Vancouver shut down the pub and a “Not Safe to Occupy” sign was posted on the front door, citing a compromised floor structure.

Balmoral tenant and retiree David Laing said everyone in the eightfloor building had concerns when word spread that the beam in the basement had broken.

“It has been the talk of the corridors,” he said. “The bar collapsing is a concern.”

Shortly after the city shut down the bar, a work crew went into the basement one night and noise could be heard right through until the morning, Laing said.

Laing, a former tradesman, said tenants feel the beam problem needs professional attention, not a crew working throughout the night.

“If I’m in there having my 53rd beer, I definitely don’t want the floor collapsing when I get up to leave,” he said.

On a piece of cardboard tacked to a wall of the basement, some rudimentary instructions had been scribbled in black marker on how to make the repairs. As soon as the city learned about the work going on in the basement, the site was shut down.

The Sahotas’ ad-hoc repairs are not limited to the Balmoral. In the spring, the facade on the weather-beaten Regent Hotel began to crumble and fall onto the sidewalk below. The owners assembled a work crew to start repairs but the city shut down that work project.

The Regent is now covered in blue sheeting and repair work on the facade has yet to commence.

“We have seen this happen before. When the city gets involved, they (the Sahotas) get motivated,” says engineer Mark Emanuel, whose company, Spratt Emanuel Engineering, is involved in restoration work on buildings owned by the Sahotas.

Reached by telephone, Gudy Sahota said he did not want to discuss the structural damage at the Balmoral.

“The city is in charge, not you. They know what is happening,” he said.

Andreea Toma, chief licensing inspector of the bylaw and licensing department at Vancouver City Hall, said in an interview last week that she has run out of patience with the Sahota family and it is time for action.

“Right now, there are 48 violations across all five building,” Toma said of the family’s SRO hotels. “We have issues at the Regent and issues continue to come up there.”

She said the city moved quickly when the beam collapsed at the Balmoral, as the bar was still open for business despite the floor buckling and being on the verge of collapse.

She said the city was concerned the entire building could fall down.

“They kept the bar open thinking they could do the repairs,” she said. “There was a life safety issue there.”

Toma said city inspectors are well aware that unskilled labour is often used on repairs at Sahota-owned SROs.

“They have a reputation of trying to find a way to give tenants a chance to do the maintenance,” she said. “The Sahotas are notorious for hiring staff that aren’t professionals.”

She maintains the city is now taking a no-nonsense approach with the Sahotas.

“We bring the Sahotas into my office on a monthly basis,” she said of the ongoing issues.

Each of the SRO rooms the family owns is checked on a yearly basis, said Toma. Due to a lack of action on repairs by the landlords, Toma said the city is now ready to go to court.

“They have left us no choice and it is going to be up to a judge,” she said. “We have spent a lot of time and energy with them.”

Under the city’s Standards of Maintenance Bylaw, Toma said they can seek fines of up to $10,000 for infractions.

Sue Collard has trouble containing her emotions when she talks about the Sahota family as landlords.

From 2008 to 2010 she lived in and managed the Sahota-owned Kwantlen Park Manor in Surrey’s Whalley neighbourhood.

“It would be difficult to call them anything except slumlords,” she said of the Sahota family.

She recalls how the 50-unit building, which Waterford Developments has owned since 1989, became extremely run down due to a lack of maintenance, with the roof in need of major repairs. Parkash Sahota is listed in public company records as the sole director of Waterford.

“There was a major rainstorm and, immediately after, leaks were discovered in four suites,” Collard said. “You had to put buckets down.”

After she complained about the living conditions in the building, she was given an eviction notice.

“Why is it the provincial government lets people like this get away with these things?” she asks.

Collard and other tenants sought relief from the RTB and in March 2012 it fined landlord Gudy Sahota $115,000 for ignoring several orders to remove mould and repair extensive water damage in the building.

But in a controversial agreement with the RTB dated Aug. 22, 2012, it was decided the fine would be waived if the Sahotas met a number of conditions, including finishing the work on the property and a resettlement package for tenants who had to find other accommodations.

Collard, who now lives in Langley, said seeing the Sahotas dodge the fine was heartbreaking.

“It was disappointing,” said Tabetha Naismith, Newton chair of housing advocacy group ACORN.

“They get such a heavy fine lifted. If they are going to fine them, then they need to hold that landlord accountable.”

Today, the building is a recovery house for drug addicts and is home to only about a dozen people. According to property records, the 2016 value of the property was $3.38 million.

Kwantlen Park Manor isn’t the only Sahota-owned building that low-income tenants were forced to leave due to critical structural problems.

In 2007, the roof of the Sahotas’ SRO at 2131 Pandora St. in Vancouver collapsed, leaving 81 people without shelter. No one was seriously injured, but the incident highlighted the deplorable living conditions of the tenants.

“I’m fighting for the people they take advantage of,” Jack Gates said.

When informed about the City of Vancouver’s plans to crack down on the Sahotas, Gates replied: “I think it is encouraging the city is getting tough on them. That is really good.

“We need all the help we can get.”

© 2016 Postmedia Network Inc