Out goes the stainless steel desert, in comes a warm, multi-purpose room with wood everywhere

Karen Gram

Sun

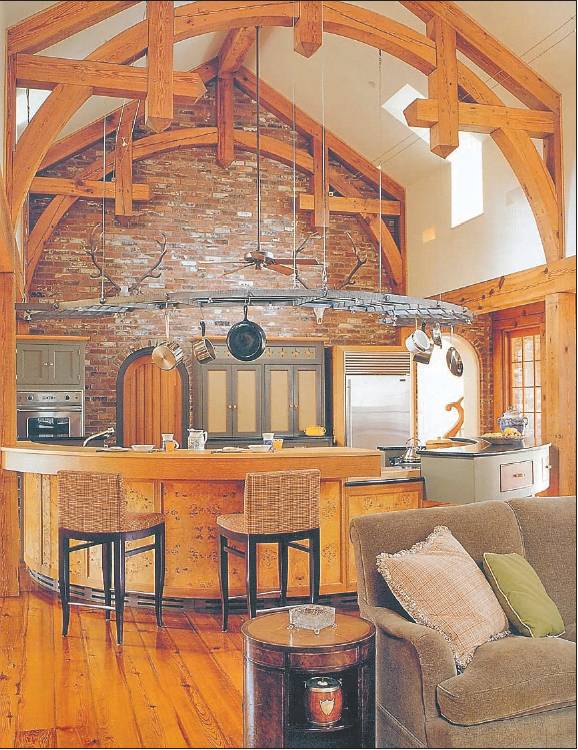

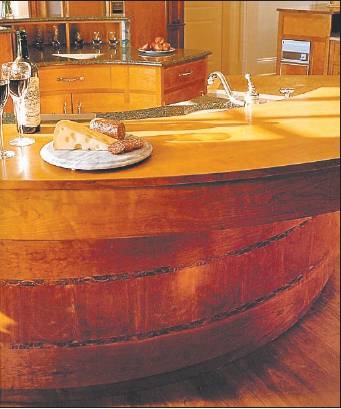

Designer/author Johnny Grey has reinvented the kitchen with the accent on wood’s welcoming glow (above). He sees the kitchen as a sociable place where people can meet and where the chef is preferably looking out onto a relaxing scene, such as a garden. Definitely out are cabinets running along the wall. ‘Over,’ he says.

Gentle curves over hard edges in kitchen design

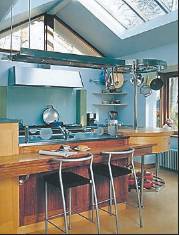

Johnny Grey’s kitchen design shuns the so-called work triangle for a sociable space, including bar stools at a wooden countertop.

The culture of a Johnny Greydesigned kitchen is one in which the space becomes a room where family and friends can gather in a relaxed and inviting setting

Johnny Grey eats breakfast like a normal guy, but he’s really a god, a kitchen god to be precise. The world famous kitchen designer, who has repeatedly blazed radical new directions in the fad-frenzied industry, was in Vancouver to preach the gospel recently.

He’s a rumpled god, long and lean, his grey hair mussed and his light linen jacket slightly wrinkled as befits a stylish, successful guy. Over breakfast at his hotel, Grey, a trained architect and author of several books including The Hardworking House and his latest, Kitchen Culture, talked about the need to revolutionize kitchen design. He says eventually new homes should be designed around his ideas, but for the time being, he just wants home-owners and designers to understand the principles he lives by. He’ll continue to tear down walls, both in the figurative and literal sense, until the revolution is here.

Grey is the fellow who started the whole unfitted-kitchen movement, in which long banks of cabinets and counters were replaced by individual pieces of furniture, each with its own personality.

He hit a zeitgeist. “All I did was point out to people what was so bloody obvious, which is what you don’t want a kitchen . . . a scientific laboratory full of plastic and fluorescent lights. What you want is a space that can be comfortable.”

That was back in the 1970s and it came about because of his great love of wooden furniture. He still loves it, still uses it, but now he’s onto something else. Something he calls the “active living space with a culinary zone,” otherwise known as the kitchen.

Grey says the modern home is deconstructing and the kitchen is extending into all the major downstairs rooms. The kitchen and dining room have long been connected, but now the kitchen has also invaded the living room and if he has his way, also the front hall and back terrace.

“It’s getting to the point where we are putting staircases into the kitchen,” he says. “It’s not a room, it’s a thoroughfare.”

A thoroughfare with several zones — one for food prep, another for eating, another for relaxing on sofas, perhaps a secondary eating zone, perhaps a computer zone. It’s an active living area with all the accoutrements of life.

Grey has been working with a neuro-scientist, who through science, confirms what Grey thinks instinctively. People have hard-wired needs for hearth, sunlight, nature, art, music, smells and most importantly, people’s faces. All of that belongs in the kitchen, he says, especially people’s faces.

“We can’t have sociability unless we can see faces,” he says. “We need to face into the room. All these kitchens with cabinets running along the wall — useless. Over. Really bad design. Consumers need to find this out. Cabinets are fine for storage, but not for working.”

That is why every kitchen Grey designs has an island where the prepping and cooking take place in such a way that the cook looks out, never towards the wall. Grey starts by locating what he calls the driver’s position. That is the premier spot, from which there is a view of the garden or nature, a view of the table, the hearth and the entrance. It’s where food prep and, ideally, washing up, occur.

He hates the “stainless steel deserts” that modern kitchens have become. He wants the room to be a warm, welcoming place in which to relax. He uses a lot of wood, gorgeous wood moulded into stunning pieces of furniture, and colour — lots of colour.

“You need the artifacts of culture around you,” he says, explaining why his kitchens often incorporate antiques, paintings, and perhaps a Persian rug.

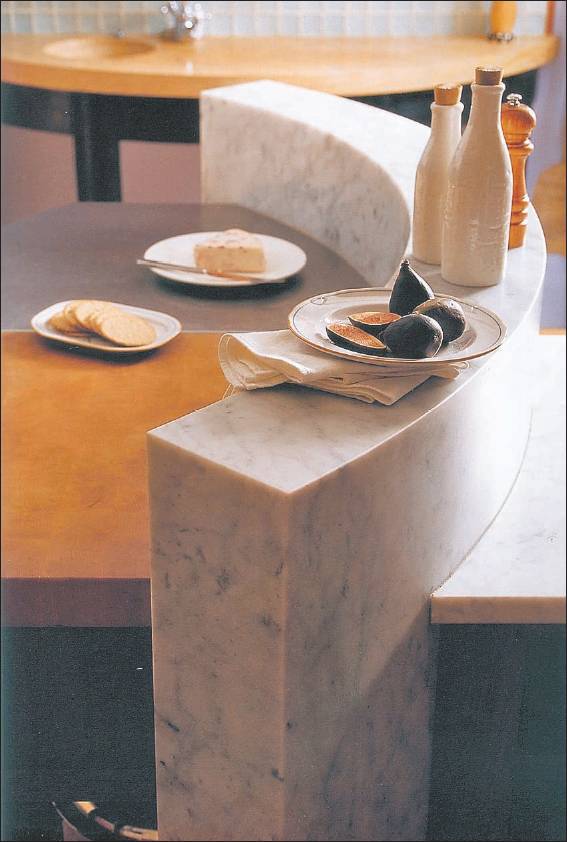

The human touch is also evident in Grey’s use of “soft geometry.” No sharp angles for him. He loves curvy lines, round cabinets, surfaces that bend gently. He says it’s not just an esthetic, but is actually a nod to the way the eye works.

He says straight lines are all very good if you are looking straight ahead, but peripheral vision activates the self-defence mechanism in the brain so if the view from the side of the eye contains any hint of danger, the brain can think of little else.

“So particularly on things in the middle of the room, like an island, you don’t want sharp corners,” he says. “It’s not a nice idea. It’s a functional idea.”

His own kitchen, in West Sussex, England, where he lives with his wife and four children, is a large, almost country-style room with a lot of colours, multiple heights and his prototypes for soft geometry. It also has French doors leading to a terrace, with long views across big hills. “So being in this kitchen is a nice place to be. That is really important — getting the environment right.”

There is one kitchen design issue Grey wants tossed down the garburator with all the other rubbish in the kitchen. That’s the work triangle. Little aggravates him more than this persistent notion that to make a kitchen function, it simply needs a three point connection between the fridge, sink and cook-top. “A gross simplification,” he says. “Almost useless in terms of real design.”

Where do you prepare food in that triangle?” he demands. What about storage, or the position of the table, or the dishwasher. “It’s ridiculous. It’s a silly way of looking at kitchen design.”

Grey says there are 13 or more elements to consider in this active living area, not just three. The kitchen designer’s job is to provide a sense of order, he says. So everything has a home. While he says Americans have shown an astonishing lack of innovation when it comes to kitchen design, he credits them with the appliance garage, a cabinet in which all the counter-top appliances can stand, plugged in, but behind a closed door.

Grey also knows that kitchens can get messy, so he builds in low visual screens to hide the mess.

He believes the modern kitchen should accommodate the busy lifestyles and special diets of today’s families. While eating together at a table is wonderful, few families can manage it during the week. “It’s okay to create a kitchen that acknowledges the reality,” he says letting his inner therapist out for a moment. He suggests a raised food bar along one side of the island where families can scarf the reheated left-overs or take-out when necessary and a table for weekends and other slow times.

Grey’s proselytizing reached a receptive audience in Vancouver. More local designers and consumers came to hear him than came to his San Francisco talks. It’s nice, he says. Gods like to be heard.

“It’s pretty nice to come to a community of people who really are interested in being aggressive with design,” he says. “Because the kitchen industry is not a very design-aware industry. It’s sales driven and that means innovation is very low on the list.”

He aims to change that.

© The Vancouver Sun 2006