Organizers of the 2010 Winter Olympics have learned the hard way

Jeff Lee

Sun

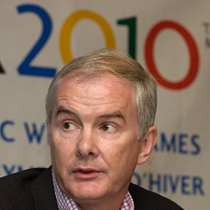

Vanoc CEO John Furlong and his executive team have had to cope with a myriad of scenarios since winning the bid for the 2010 Olympics, including rising costs and altered event locations. Photograph by : Ian Smith, Vancouver Sun Files

Three years ago last month, in a ceremony that sparked celebrations across Canada, International Olympic Committee president Jacques Rogge uttered the memorable words awarding the 2010 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games to Vancouver.

The award capped a four-year quest to once again bring the Olympics to Canada, and the bidding group had pulled out all the stops.

It promised a jewel of an event, with gleaming new state-of-the-art venues scattered between the Lower Mainland and Whistler.

But since that heady day, much of the original promise has changed. The phrase “on time and on budget” is only relative when you consider that the venues will be on time when the Games start in February 2010. They’ll have to be. But they will hardly be on budget. Or as grandiose.

In fact, the $470-million construction budget, which has now ballooned to $580 million even after many venues were revamped or moved, is hardly the tip of what taxpayers face.

Add in the $175-million Olympics-only security budget, the untold millions that will be spent by local governments for extra policing necessary for indirect Olympic events and traffic, the $600-million Sea to Sky Highway upgrade and the several hundred millions of dollars the federal and provincial governments are spending to orchestrate and promote the Games for economic leverage.

It is not hard to believe that the public tab could one day exceed $1.5 billion.

And to boot, there is hardly a venue that hasn’t changed from when it was first proposed.

So was the public misled? Was the bid really all that accurate, or was it a document designed to woo the IOC, giving it what it wanted to see? Why is it that no Olympics in modern history has ever looked like the one originally proposed? They are almost always smaller and more expensive.

Consider some of what has happened since the bid book was dropped off in Lausanne, Switzerland by then-mayor Larry Campbell, then bid president John Furlong (now Vanoc’s CEO) and then-bid chairman Jack Poole (who is now chairman of Vancouver Organizing Committee):

– A new $60-million speed-skating oval promised for Simon Fraser University has been moved to Richmond and will now cost $178 million (with Richmond picking up most of the remaining $115.3 million).

– The new $55-million bobsled and luge track at Whistler is now billed out at $99.9 million.

– The proposed $102-million Nordic centre in Callaghan Valley will cost $115.7 million, even after it was substantially scaled down, with ski jumps scrapped or made temporary and plans for many trails abandoned, to the detriment of future sport development.

– A new $36-million international-size hockey rink at the University of B.C. will now cost $48-million and has been whittled down to NHL-sized ice.

– That $28-million curling rink promised for a vacant lot in Vancouver will now cost $37.1 million and has been moved to a heritage ball park, which will be destroyed in the process.

– The $35.5-million athletes’ village at the start of the Callaghan Valley was moved closer to Whistler, and will cost closer to $45 million, as part of a $150 million new community subdivision.

– A $15-million international broadcast centre on the former coast guard lands in Richmond was scrapped in favour of moving all the media to the expanded Vancouver Convention and Exhibition Centre.

– A new $20-million arena for Paralympic sledge hockey in Whistler is now estimated at $45 million to $50 million and may well be scrapped, forcing Vanoc to move the event to Vancouver.

And none of that includes other costs B.C. taxpayers didn’t know they would bear when the bid was concocted.

Those include $130 million for Legacies Now (a government-funded program to create sport and community legacies arising from hosting the Games); $26 million for the B.C. Olympic Games Secretariat, the government agency overseeing the province’s commitments; $12 million for a provincial road into the Nordic centre; $6 million for a log show-home at the Turin 2006 Winter Games, and a raft of other tourism and economy-boosting incentives framed around the 2010 Games.

The province says the Sea To Sky Highway upgrade isn’t directly attributable to the Olympic Games. The Auditor General of B.C. says it is.

The feds have their own Olympic secretariat in Ottawa. They also have promotional programs to make sure these are seen as Canada’s Games.

Before you think that’s the final tab, consider this: it doesn’t include the cost of actually operating the Games, pegged at more than $1.7 billion — up from the original estimate of $1.35 billion. One small mercy is that those funds are supposed to come from corporate sponsors, television revenues, lottery proceeds and ticket sales, and not the taxpayers’ pockets.

There are some huge pluses, however, that Vanoc and the IOC have achieved to help soften the blow.

Vanoc craftily negotiated some of the richest marketing deals in Olympic history, raising so far nearly $600 million from a handful of sponsors. It also saved $10 million by folding the Richmond broadcast centre into the downtown Vancouver convention centre, and another $10 million by convincing the International Ice Hockey Federation to play on the existing NHL-size ice at GM Place.

The IOC has also signed record-breaking deals for U.S., Canada and European television broadcast rights. What share of that will go to Vanoc is not yet known, but the optics look good for the organizing committee.

The governments argue the Olympics are creating spinoff opportunities in the form of destination tourism and training facilities; Vancouver Island will have a new cross-country skiing resort, Fort St. John gets a new speed-skating oval and Prince George is building new ice sports facilities at the University of Northern B.C.

Vanoc aggressively reworked all of its venues with a practical eye towards justifying everything that it needs to build. With Montreal’s infamously over-budget billion-dollar stadium built for the 1976 Summer Olympics not too far back in their minds, Vanoc officials have questioned every conceivable expense, to the point that Furlong has taken to video-conferencing with the IOC rather than make expensive flights to Europe.

Yet with all that, the Games Canada was promised still has been substantially altered.

Many of the changes are being blamed on a strong economy and a building boom that started in 2002 in both the residential and non-residential sectors. China’s voracious demand for steel has also pushed prices sky-high. And the Independent Contractors and Businesses Association of B.C. estimates that construction costs in B.C. could rise 50 per cent by 2010.

The falling foreign exchange rate has also hurt Vanoc; the estimates were prepared when the Canadian dollar traded at $1.55 to the US. That’s because a large portion of Vanoc’s operating costs come from the IOC’s television revenues, which are paid in US dollars. Since the bid was won, Vanoc has lost millions of dollars in exchange value, even though it sheltered some money by hedging on foreign currencies.

Most importantly, the bid was prepared in fixed 2002 US dollars as required by the IOC, meaning that with inflation, it was already out of date before construction even began.

By April 2004 — less than two years after the bid budget was built — it was clear to Vanoc that costs were seriously out of whack and that it would need to apply to the province for a “supplementary budget.”

The province at first balked, but now has agreed to chip in $55 million more if the federal Conservative government matches the amount. Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s government hasn’t yet publicly agreed, but a decision is expected this fall.

The organizing committee is, by all accounts, pinching pennies as hard as it can while getting contractors and corporate sponsors to patriotically buy into providing value-added services at little or no cost. After all, these are Canada’s Games. Most sponsors, for example, also contribute to the Own The Podium program, which is supposed to get Olympic-level athletes ready for the Games.

But couldn’t the cost of these Games have been better estimated? If Vanoc’s executive team knew in April 2004 that its costs were escalating, didn’t it have the prescience to construct a more realistic budget for the 2002 bid? After all, many of the bid executives were hired by Vanoc.

“The taxpayers feel like they got snookered,” said Harry Bains, the Olympics critic for the Opposition New Democratic Party. He believes the Vancouver bid corporation deliberately underestimated the impact for taxpayers.

“What I’ve found is that Olympic management teams tend to underestimate costs in order to get the public on side in their respective countries,” he said.

If other businesses, such as mining and construction companies, are capable of building long-term projects on time, so why can’t the Olympics, he asks.

“We’re not reinventing the wheel. We have gone through this before and I think there are businesses of this magnitude all around the world that are planned five, six years ahead of time. You don’t see in most of them the cost overruns as you see in the Olympics.”

Giselle Davies, the IOC’s spokeswoman, said it is unreasonable to expect that there won’t be changes in the evolutionary life of an Olympic bid.

“It is relatively commonplace for a project that spans seven years — nine if you include the bidding phase — to have adjustments that take place,” she said Friday from Switzerland.

In recent years the IOC has insisted on much more detailed bids, and road-tests them with an evaluation commission. It is not in the best interests of the IOC or the international sporting federations to accept bids that are not adequately planned, she said.

“Having said that, the nature is that you are expecting things to change somewhat over nine years. It is natural that there will be changes.”

Vancouver first started its run for the Olympics in 1998, beating out Calgary and Quebec City for the Canadian Olympic Committee endorsement. Then Vancouver ran against an international field, which was shortlisted to itself, Salzburg, Austria and Pyeongchang, South Korea in 2003. In July, 2003 Vancouver won against Pyeongchang by two votes.

George Hirthler, an Atlanta, Georgia communications strategist who worked on the Vancouver bid several years ago, said bidding cities don’t deliberately mislead the public. They can’t afford to, he said.

“There isn’t any deception involved in the process of bidding,” said Hirthler, who has worked on eight Olympic bids and is now working on Salzburg’s bid for the 2016 Winter Games.

“I think it is just reality that it [the bid] gets changed. The community itself may begin to change it. The city may have an agenda on how things are built. And the IOC may see something more favorable in shifting elsewhere. It is extremely natural evolutionary process in the development of a decade-long program.”

Keith Sashaw, president of the Vancouver Regional Construction Association, laughs at that idea that Vanoc could have foreseen or better predicted the costs and changes.

“This is not a unique situation, Anybody who has renovated their kitchen has experienced the same kinds of problems Vanoc has encountered,” he said. “When the bid book was created in 2002, nobody would have anticipated the costs increases we’ve seen.”

Sashaw said private-sector developers have limited choices when costs go up. They either raise the price of their units, scrap the entire project, or engage in cost-cutting exercises by changing materials and scope of work.

“And that is exactly what Vanoc has been doing,” he said. “They’ve been cutting costs wherever they can.”

Sashaw said it is good that Vanoc is aggressively cutting out things it doesn’t think it needs, regardless of what the bid corporation pledged in 2002.

“Vanoc recognizes that they don’t have an open wallet they can be dipping into. I don’t think we’re looking at a Montreal billion-dollar stadium.”

But Bains is unconvinced. He believes the public is fickle about big projects that go over budget.

“I think the public will be paying a lot more money than they expected.”

He pointed out that the late NDP government was tossed out largely as a result of the fast ferries scandal, in which the catamarans, first estimated at $210 million, actually cost $454 million and were eventually auctioned off for $19.8 million.

“Well, [former NDP premier] Glen Clark lost his election on fast ferries overruns, and it wasn’t even close to this,” Bains said.

© The Vancouver Sun 2006