Icon gives nod to ‘Brazil mod’

Frances Bula

Sun

Architects Nick Milkovich (left) and Arthur Erickson show off a very basic model of a building in Olympic athletes village area. Photograph by : Ian Smith, Vancouver Sun

Punch-drunk from fatigue and firing intensely on all creative cylinders. That’s the feel in the design team creating Vancouver’s Olympic village these days, as they pull university-style all-nighters and compress a month’s work into every week to meet their looming deadline.

Millennium Development, with its dozens of architects, designers and builders, has 32 months and 15 days until it has to hand over the keys to 1,100 units of condos spread out over eight buildings.

The project, which covers nine city blocks, is also supposed to be accompanied by urban gardens, waterfalls and pools, landscaping, commercial spaces and a community centre.

And the whole neighbourhood-in-a-bag is expected to set a new standard for green development in the province, if not North America.

In comparison, it took about seven years to build the Arbutus neighbourhood on the old Molson brewery site in Vancouver, which is the same size as the Olympic village will be in southeast False Creek.

And that project didn’t have anything approaching what has gone on in the past 10 months with the Olympic village, which has become a drama worthy of Shakespeare if he had taken an interest in urban planning instead of Richard III.

The southeast False Creek marathon started out on a sour note after a new city council decided to abandon a previous requirement that one-third of the housing be aimed at middle-income Vancouverites.

Then Millennium won the bid with a $193-million offer, setting a record for city land prices.

For many, those two events combined to symbolize a feeling that the village, originally planned as a “socially sustainable” mixed community, was going to become just another piece of Vancouver’s waterfront sold off to the rich, like others of the recent past.

Then, city planners, an active community oversight group, and the developer team spent the summer in epic struggles over how to balance building a leading-edge green project and building something that will make money.

Realtor Bob Rennie, one of a handful of people who has played the role of mediator many times among the parties, said early meetings would have as many as 90 people in them, “most of them with bike helmets and heavy wool sweaters.”

Those were the first of what would become a series of debates over the two sustainabilities that are supposed to be part of triple bottom-line thinking in green developments: the environmental and the economic. The environmental advocates wanted a radically innovative project that would be a world model. The economic advocates wanted something that was green, but salable at the top dollar it would take to make the books work.

The developer’s insistence on putting in air-conditioning prompted an especially passionate debate over whether air-conditioning could be included in a project that called itself green.

In the fall, one of the team’s original architects, Robert A.M. Stern of New York, was asked politely to withdraw after weeks of pressure on Millennium by city planners and the urban design panel. They wanted the project’s most prominent waterfront building to be designed by someone who would express the look and feel of Vancouver, not an outsider — especially an outsider with a history of building neo-classical palaces for New York’s money set.

As buildings and details started to take shape, some of the more utopian ideas, like creating mini-forests on every deck, were abandoned.

Then, last month, everyone was knocked off balance by the tragic sudden death of the team’s key sustainability consultant, Andy Kesteloo, who was only 47.

Despite all that, the village concept — being called Millennium Water — is starting to emerge on paper, as the city’s contractors and crews are busy reshaping the southeast False Creek waterfront, trucking away contaminated soil, and preparing for the construction that needs to start as soon as possible.

Vancouver’s iconic Arthur Erickson, brought in to take over the project’s most prominent site, has transformed what was originally envisioned as a wall of solid building on the seawall by splitting it. It is now two gently curving crescents facing each other, with a public water garden between them.

The community centre to the east, the other prominent waterfront site which he is co-designing with Walter Francl, has become a long, low lantern with colours glowing from the interior through translucent glass. The split roof swoops twice, like waves running along the ocean horizon.

The two pieces, strikingly unlike anything else in Vancouver’s forest of silver towers in the downtown peninsula, are what Erickson is calling “Brazil modernism” brought to Vancouver.

Throughout the rest of the village, in spite of continuing concerns about the project simply not having enough time, architects or sustainability expertise to do the best job, people are getting cautiously excited about the innovations, in green building and in architecture, that are emerging.

“Some pieces of it are close to world-class. The net-zero building — that’s leading edge,” says Tom Osdoba, the city’s sustainability manager, referring to a seniors’ residence in the complex that will become the first building in Canada that produces as much energy as it uses.

And the look of the background blocks of the village, which will frame the two individualistic waterfront buildings, will also be something that hasn’t been seen in Vancouver before.

The complex combines traditional city blocks with a new style of architecture that is reminiscent to some modern developments in Europe. The mass, height and groups of buildings are similar to older parts of the city, but the architecture itself is modern.

“This is a very different experiment,” says architect James Cheng, until last month a member of the city’s urban design panel, who has watched the project evolve slowly. “It’s much more like Europe, like the facades at Nice and Cannes, where the buildings define the waterfront.”

All of that arose after a particularly painful session between the city’s urban design panel and the architecture team last fall, where the panel members drilled the message home that all the plans they’d seen so far didn’t express any distinctive identity for the village.

“We did have different opinions, so many that it was obvious we were never going to reconcile them,” said architect Stu Lyon. “The city had an image, the developer had an image, the architects had an image. None of those approaches were working really well.”

After that, Lyon, whose firm along with Merrick Architecture is doing the non-waterfront buildings, came back to the team with a set of 10 principles that could be used as a guide for the dozen-plus architects as they worked out the hundreds of big-picture concepts and tiny details that form a project this size.

Those principles boil down to:

– Create a link between the public outside and the residents inside buildings by making everything more visible.

– Put hallways around the outsides of the buildings.

– Make the elevators and staircases visible.

– Create vertical streets and horizontal sidewalks above the ground.

– Bring daylight and air in as much as possible.

– Make terraces and interior courtyards useful and connected.

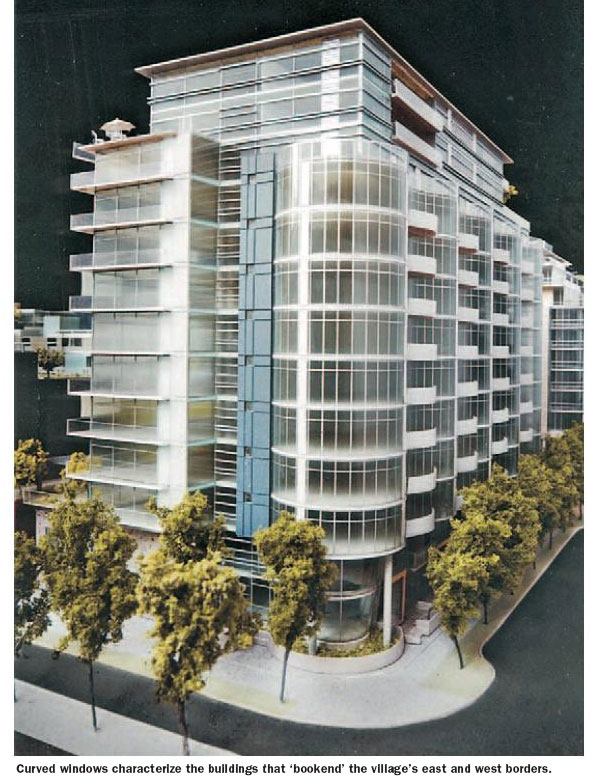

Developer Shahram Malek has also added his stamp to the project. The two buildings that bookend the village on the east and west will have unusual wave-like facades that curve in and out for the length of the building, an idea he has seen elsewhere and pushed to have included.

That’s one piece of a water theme for the whole village, which will not only have Erickson’s curved buildings and the curved bookend facades, but a series of waterfalls, pools and other features among the project’s intensive efforts to recycle stormwater. (Every building will have rainscreens, like hat brims, at the top to channel rainwater back to the roof for collection.)

And, although it’s not visible yet on the models, these buildings will have more colour than the ascetic steel-and-glass look that has characterized the city’s downtown developments for the past 15 years.

But it’s hard to know at this point what they’re going to really look like. The details of the materials aren’t on the models and aren’t even nailed down yet.

The first two buildings were scheduled to get their development-approval permits last night even though adjustments were still being redrawn up to the last minute and the urban design panel had never really seen many specifics on the materials.

“The success is going to be in how these buildings are assembled, how the detailing is pulled off,” says Scot Hein, the city planner who has been leading the whole process.

The interesting question for many people is how this project might change the city and the development industry, especially given that the developer who chose to take on this project had no history of leading the way in green building.

Osdoba said the planning process, while it’s been a huge learning curve for many, is having an impact on not just the developer but the city. “It is going to make a big difference. It’s changed the way we do things.”

Mark Holland, a leading sustainability planner, echoes that even more forcefully. He says the village project is starting to influence private developments being planned throughout the city, and particularly the city’s other mega-development, the East Fraser lands project in southeast Vancouver.

“It’s kind of setting a standard. All the professionals who worked on it are taking what they’ve learned to other projects. There’s a big transference of southeast False Creek experiences that are being spread across the country,” says Holland.

Realtor Bob Rennie, who has pushed more than one developer in the city to move out of his comfort zone, says the project has taught both sides something.

“We’re all going through an education of introducing sustainability and green into the mainstream and luxury products.”

He believes that developers have to start incorporating green because their clients want it. “I believe the luxury-brand consumer is going to start wearing sustainability as an asset.”

Even if there are those who don’t care, they will care about the resale value and green will provide extra resale value, he believes.

As a result, the architects and landscape architects have been left fairly free to aggressively pursue new concepts in urban agriculture and building design, say those involved.

“I’ve seen Millennium let their architects do what they think is right,” says Hein.

But Rennie has also pushed back on ideas he thought were impractical, like having a small forest on every deck or eliminating air conditioning.

“These people know more about sustainability than I will ever know, but we have to become the voice of reason on the other side, saying how much will the consumer be willing to live with and willing to pay for.”

The project has also introduced a new kind of design process.

Typically, buildings go through heavy scrutiny by city hall and the urban design panel, and they are checked for their conformity to very specific neighbourhood design guidelines.

That has produced a level of good, but not outstanding architecture, as more than one critic has observed.

The time pressure has meant that city planners simply don’t have the luxury of vetting every detail. Some critics say that means the designers don’t have the time to think through all the complex issues or to add any sophistication or depth to their work.

But others say the exceptional time crunch has created an atmosphere of white-hot creativity that is a benefit.

“I think it probably will improve the product,” says Lyon. “There’s less time to waffle.”

Hein says the city has had to leave a lot more to the architects than usual — and that’s good.

“We don’t have a lot of significant architecture,” says Hein. “This will maybe free up the industry.”

In the meantime, there are two more months of hard design work to go. And then the building begins.

© The Vancouver Sun 2007