Four high-tech veterans create circuit card that brings big boys’ backing

Gillian Shaw

Sun

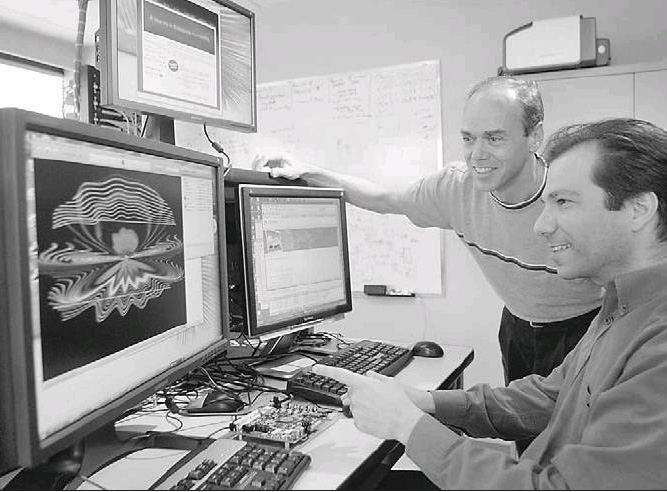

Dave Hobbs (rear), founder and chief architect of Teradici, oversees testing of the company’s new device that allows companies to replace desktop PCs with remotely accessed computers. The operation is carried out by senior staff engineer Dave Garau in the Burnaby lab.

Teradici’s chief architect, shown here with one of the company’s new chips that allows businesses to replace desktop PCs with Internet-accedded circuit cards.

One day they are four guys sitting around public library meeting rooms and dreaming about their far-fetched plans to reinvent business computers.

The next day they’ve hit pay dirt, sitting on $34 million US in venture capital, and the heavy hitters in computer manufacturing are lining up to buy their computer chip technology that replaces traditional desktop computers with a puck-sized Internet-connected portal.

No microprocessor chips, no memory, no operating system, no hard drive, CD or DVD — it adds up to a stripped-down, low-cost, low-maintenance and even more importantly secure substitute that can replace full computers on corporate desks.

At the heart of the meteoric rise of the Burnaby-based Teradici Corp. is a seemingly simple concept — PC-over-IP.

“We started thinking that, rather than having desktop PCs sitting on everybody’s desk, why don’t we put those desktop PCs back into the data centre,” said Dan Cordingley, the company’s president, chief executive officer and one of its co-founders. “If we could do that, everything would be secure and very easy to manage.”

The answer to bridging that link between the user and the data centre was a chipset that compresses and converts the display data, along with the USB signals used by PC accessories, into the digital format of the Internet and corporate networks, thus creating PC-over-IP.

And because it’s part of a computer — the difference being the computer isn’t in a box sitting on the desk but rather in a data centre that could be in a another city — the person tapping into the keyboard gets the same features and capabilities, including sophisticated graphics and sound, as a full desktop PC.

“It is everything you have on a normal PC,” said Cordingley. “Only now rather than being in one of those beige boxes under your desk, it is now just a circuit card back at the data centre.”

The concept is the brainchild of Cordingley and three fellow tech veterans, who could have all retired as millionaires when the various companies they were involved in were bought up. Instead, they started meeting — in each other’s homes, in restaurants, in libraries — to discuss a new concept for delivering computing power to the desktops of large enterprises.

Cordingley’s resume reads from IBM to Intel, which bought the California company he worked for, Level One Communications, with stops at Spectrum Signal Processing and other tech companies in between. His co-founders include Dave Hobbs, a former vice-president of engineering and chief technical officer at Spectrum Signal Processing; Ken Unger, formerly director of engineering for VoIP products at Broadcom Corp., which bought out HotHaus Technologies where Unger had been a member of the engineering team; and Maher Fahmi, formerly a director of product development at PMC-Sierra.

Other companies have been able to produce the stripped-down PC replacements that are known as thin clients. But Teradici has gone much farther.

Thousands of kilometres farther, in fact, delivering PCs over the Internet by connecting the heart of the computer via the Internet instead of by a cable across a desk. The distance is only limited by simple physics — when it’s too great there could be too much latency and the performance would be sluggish. But across town or across regions works.

It makes it far easier for large companies and organizations to manage and maintain their computing resources, and delivers a powerful security boost to industries that are under increasing pressure to protect data and guard privacy.

The company has been operating under the radar, going from the early casual meeting places to a 55-person office in Burnaby. On Monday, it lifts the veil off its technology, launching it in New York at the Securities Industry & Financial Markets Association technology conference and exhibit.

While it hasn’t been overnight, the company has gone from incorporation in 2004 to signing on its first major client, IBM, within a few short years. And commercial delivery of its first products is expected in the third quarter of this year.

It first attracted the attention of Vancouver’s GrowthWorks Capital, which led the initial financing that saw the fledgling company get about $8.5 million US from GrowthWorks and the Business Development Bank of Canada. Another $8 million in venture capital came last year, and a further $18 million earlier this year, with the investment now expanded to include money from Silicon Valley, eastern Canada and the U.K.

“We were taking a big bet we could attract more venture capital in the short run rather than in the long run so they could get their first product to market,” said Joe Timlin, a vice-president of investments at GrowthWorks.

Not only were the dollars needed to reach commercialization substantially higher than for a software company, at the time the market was unknown.

“At the time we invested there was no market for their products,” said Timlin. “It is so innovative we were taking a bet the market would develop in such a way it could consume Teradici’s technology.

“These guys have not only boldly guessed where the market would go, but they have been good enough to actually influence where the market would go.”

The founders also won the support of some big names on the tech scene, and Timlin said having Kevin Huscroft, a founder of PMC-Sierra, on the board, along with Randy Groves, a former chief technology officer with Dell, only helped sell their story.

“These were not guys out of MBA programs or engineering programs founding a company on a whim and a hope,” he said of Teradici’s founding team.

Co-founder Hobbs, now Teradici’s chief architect, remembers long hours at home doing research and running simulations and meeting anywhere they could find space.

“In talking to people about the challenges large enterprises face, it would be, ‘How do you control software, how do you control security?’ There is the cost of maintaining all these disparate PCs on the desks.”

The feedback told them that if they could overcome the challenges in delivering the full PC experience without the PC box attached at the desk, it could win favour with customers.

“It was worth the risk,” said Hobbs. “If we could make it work, based on the market intelligence we were able to gather, it could be a very big market.”

Already it is making waves, largely thanks to the talent they have been able to find in Vancouver.

“The technical talent pool in Vancouver is really first-rate. We have been able to build Teradici with just fantastic engineering folks,” said Cordingley. “Our investors were amazed our chip came back and worked virtually 100 per cent right out of the gate.

“Within the first four weeks of delivering our first sample of the chip to IBM, they were demonstrating it to the major financial institutions on Wall Street.”