Critics debate safety of debit-card system as rise of electronic transactions spawns new breed of thieves

Sun

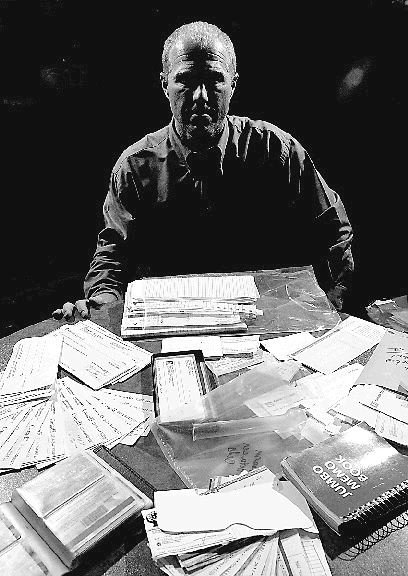

Edmonton Police Service Det. Allan Vonkeman displays confiscated cheques, bills, credit cards and miscellaneous personal identity stolen primarily from various apartment mailboxes in the city. Photograph by : Larry Wong, CanWest News Service

TORONTO – The problem of theft in Canada is no longer about teenage shoplifters, black-masked bank robbers or purse-snatchers. The rise of the electronic payments system has spawned a new breed of thieves who can clean out the bank accounts of unsuspecting victims with a simple swipe of a card.

The profits from these crimes frequently fund organized criminal networks, according to police forces across the country, which are grappling with the growing problem.

Often referred to under the broad category of “identity theft,” payment card fraud in its various forms presents a growing threat to Canadians — one the country’s banks, card issuers and retailers aren’t eager to talk about.

In some cases, hackers steal piles of customer information that companies store electronically, as was the case earlier this year with the high-profile security breaches at the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce and TJX Cos., the parent company of Winners and HomeSense.

Criminals also tamper with bank machines and debit card machines to electronically record a customer’s account information and make counterfeit payment cards. In other cases, employees — particularly at restaurants, gas stations and convenience stores — swipe a customer’s card through a small magnetic strip reader that records account information, and use it to make fake payment cards.

“What we’ve found is that the criminals involved in this are involved in a wide spectrum of criminal activity,” said Insp. Barry Baxter of the RCMP’s commercial crime branch. “The profits generated from this go to drugs, weapons, prostitution, loan-sharking, lifestyle.”

But compared to company profits, fraud losses are minuscule. Less than half of one per cent of all payment cards were hit with fraud last year, according to Caroline Hubberstey, director of public and community affairs at the Canadian Bankers Association.

Losses represented one-10th of one per cent of the sales volumes of credit card companies, said Gord Jamieson, Visa Canada’s director of risk and security.

But if the problem of payment card fraud is under control, why is the financial industry so resistant to informing Canadians about how and when frauds occur?

In most cases, banks, payment card companies and businesses do not tell Canadians who fall victim to payment card fraud how and where their personal information was lost or stolen. Part of the rationale is that disclosing such information could jeopardize a police investigation, according to the bankers association.

But a major reason the industry wants to keep vital details from Canadians is they’re worried consumers will boycott the stores or banks where they got ripped off.

“What it could do is have an adverse impact on that merchant and future sales, their business and everything else,” Jamieson said. Banks and card issuers say consumers are more interested in knowing they’ll be compensated for losses than finding out where and how their personal information was lost or stolen by criminals.

Canadian banks, card companies and businesses say they should be able to decide whether to tell customers when their information is lost or stolen. Although the industry follows a voluntary code that encourages disclosure when the risk of fraud is high or imminent, there is currently no obligation to inform consumers when they suffer a security breach.

The industry’s complete discretion over breach notification, however, has raised serious alarm. Earlier this year, federal privacy commissioner Jennifer Stoddart urged a parliamentary committee to make breach notification part of federal privacy law. This would bring “increased attention on the part of organizations to the security in which they keep personal information and then to their duty to act swiftly and appropriately to help people,” she said.

Critics, however, say that argument is proof the banking, payment card and retail industry would like to keep the growing threat of fraud as quiet as possible to avoid scaring consumers away.

“Banks have their image and they would like to preserve it, so it’s not in their best interests for a major Canadian bank to go on the news and say they’ve been a victim of identity fraud,” said RCMP Cpl. Louis Robertson, head of the criminal intelligence unit at Phonebusters, a national anti-fraud call centre.

In the coming months, credit card companies will begin rolling out new cards that combine a secure microchip and personal identification number to reduce fraud. It’s a multimillion-dollar investment that will take several years to implement.

Many of the country’s major banks have also upgraded bank machines and online banking systems to reduce the incidence of fraud.

“You’ll see new strategies on [bank] machines — some obvious, some not so,” Hubberstey said. “This is a constant effort.”