Frances Bula

Sun

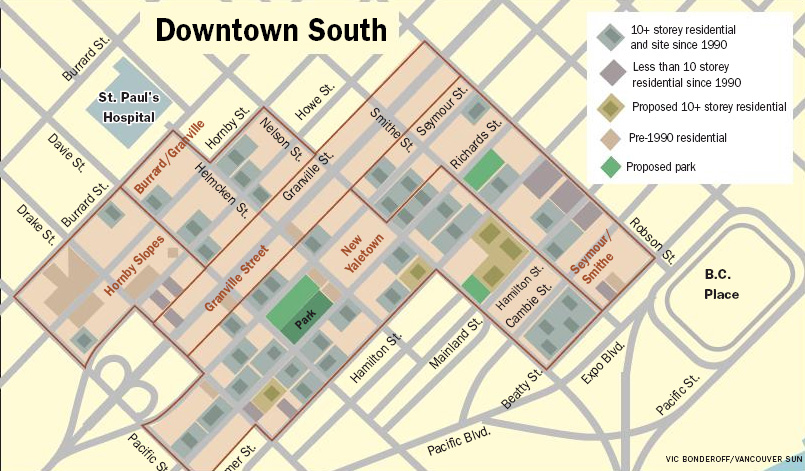

The small Emery Barnes Park is a rare green space found in the increasingly dense Downtown South, which reached an estimated population of 11,000 in 2002 — 14 years earlier than expected. Photograph by : Ian Lindsay, Vancouver Sun

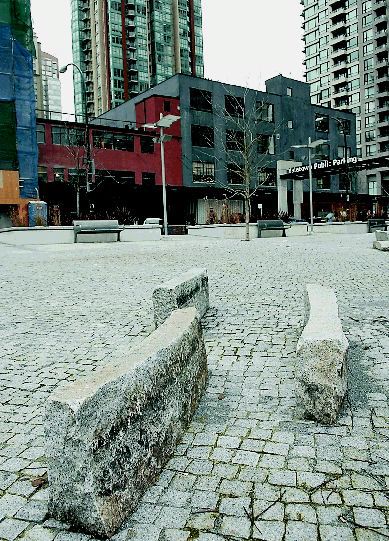

Those living in growing Downtown South say they like this spot because of its eclectic atmosphere, which has a different feel from neighbouring Yaletown area pictured above. Photograph by : Ian Lindsay, Vancouver Sun

VANCOUVER – Vancouver‘s West End has always been the flagship symbol of dense urban life for Metro Vancouver. People liked to brag it was as dense as Manhattan.

That wasn’t true, strictly speaking, but the urban myth reflected the pride Vancouverites took in having created a West Coast version of New York.

However, the West End is looking positively suburban these days, compared to what’s happening next door.

A new Vancouver neighbourhood is emerging that, when it’s built out, will pack in twice as many people per square kilometre as the West End.

No, this new mini-Hong Kong isn’t the swath of glass towers that ring the southern perimeter of the downtown peninsula.

Instead, it’s the lesser known neighbourhood bordering it that is now being called, in city planning documents and almost nowhere else, Downtown South.

It’s an artificial term the city uses to describe the irregular 35-hectare patch of downtown land that isn’t Concord Pacific, isn’t Yaletown, isn’t the West End and isn’t the central business district.

In essence, it’s the no man’s land between Burrard and Pacific Boulevard that is slowly being transformed from an irregular jumble of low-rise clubs, auto shops, hairdressers, government buildings, second-hand stores, tattoo parlours, and houses that are the last remnants of early 20th-century Vancouver into a forest of condo towers.

The 34 blocks of the Downtown South are currently home to 46 towers, 15 more under construction ranging from holes in the ground to almost done, and unknown numbers more on the way for the sites now occupied by parking or one-storey buildings.

City planners originally projected that 11,000 people would live in the area by 2016. The Downtown South hit that mark by 2002, 14 years early. The planners also thought the total population would max out at around 14,000. Now, they estimate it’s going to reach 24,000 by 2021 — 448 people per hectare, double the density of the West End, according to figures from the city planning department’s data expert, Andy Coupland.

That’s the equivalent of moving every last person who currently lives in the towns of Ladysmith, Hope, Queen Charlotte City, Revelstoke and Rossland into those 34 blocks.

The area is attracting a breed of residents for whom even the West End was a little too tranquil and remote from downtown life.

“West of Denman is very quiet,” says Roger Chilton, a 60-something arts fanatic who moved to the corner of Richards and Davie a few years ago. “Here, I can walk out to all of the theatres in the downtown.”

DIVERSITY DRAWS DENSITY

But Downtown South is also having its problems as the city, park board and schools scramble to provide services for the population explosion. That includes coping with a group no one anticipated would be part of the explosion — the homeless.

It is a critical piece of territory in the city for a couple of reasons.

This dense little pocket, unlike the swanky new Shangri-La and Ritz-Carlton towers being marketed to wealthy foreigners or the upscale enclaves of Coal Harbour and north False Creek, is where non-rich Vancouverites are the most likely to buy or rent if they want to be in the new downtown.

The area is also a living experiment in how the much-vaunted Vancouver model works when the city is not dealing with the relatively easy megaproject developments.

Those developments gave planners the advantages of, first, a single developer to negotiate with; second, lots of land; and third, nothing on that land. That allowed the city and developer to come up with a big-picture plan and a one-shot bargaining session over getting the parks, community centres, seawall enhancements, daycares and whatever else they thought was needed for the new residents.

But in Downtown South, the city has to deal with dozens of developers, a range of sites, existing buildings, and no simple way to reserve land for needed services.

The result is a lesson, both for Vancouver and for all the clusters of tower-building currently going on in the region, about the challenge of making dense places livable and well-serviced when they’re not part of a master plan.

Stop the people walking through the Downtown South, call them up out of the blue, and they’re remarkably passionate about how much they enjoy their neighbourhood.

“I love the area,” says Chilton. “It’s oddly not quite what I expected. I would have expected it to be more adult-oriented, but it’s not.”

He lives across the street from the area’s one green space, Emery Barnes Park. Yaletown, with its distinctive old warehouse buildings, is a block away. He never has to use his car; everything he needs is within walking distance.

Terry Davis, a generation younger than Chilton, is equally enthusiastic. He and his wife first lived in Maple Ridge when they moved to Vancouver in 2001. “We loved the apartment but we hated living there,” said Davis, a freelance photographer. “We like being able to walk. I really do love this neighbourhood.”

It’s got a different feel to it from any other part of downtown Vancouver. There’s even a marked difference from its closest neighbours, with Pacific Boulevard marking the boundary between the more family-oriented, park-rich, manicured and expensive Concord land on the water.

GRITTY REALITY ATTRACTS THE YOUNG

Downtown South is a land of concrete and brick, filled with repeating rows of Vancouver‘s trademark, street-level, fancifully named condos like the Freesia, the Mondrian, the Eden, their point towers rising above them, that are built right up to the sidewalks.

There’s far less green, with no mature trees, only one traditional park, and few grass boulevards. And it’s much more traffic-dominated. Unlike dense Manhattan, which is a mix of high-traffic streets and quieter residential avenues, or the dense West End, where many streets have been all but closed to traffic, almost every street running through this land-locked neighbourhood is a commuter route leading to a bridge.

On the other hand, it’s got an organic grittiness to it that many people prefer to the more manicured megaproject developments.

Katie Warfield, a 30-year-old college instructor, said she gets enormous pleasure out of the variety in the area. Within a block of her apartment, there’s Madame Cleo’s, “Vancouver’s finest sensual massage parlour” as it advertises itself, three turn-of-the-20th-century houses, a pristine silvery modernist low-rise that is a pleasure to look at, the park, occupied by the two main demographics of dog-walkers and homeless people, and the Choices grocery store.

“In the master-planned communities, you see the whole narrative laid out. But here, it’s a lot of little stories,” said Warfield, a communications graduate with a background in urban design.

It’s also young. More than 35 per cent of the residents are in the 25-34 age group according to the 2006 census, higher than any other part of the downtown.

In one way, it’s exactly what the planners wanted. The Downtown South was always envisioned as being the city’s affordable alternative to the megaprojects, since it was away from the waterfront. It was planned to be dense, but with places to go nearby for a break from that density.

“In a dense area, you need a feeling of respite,” says senior central-area planner Michael Gordon. The respite “rooms” for the neighbourhood are the older, low-rise historic streets of Granville and Yaletown, with the parks and seawall just beyond that.

The city also pushed developers to create more family-friendly projects, with two- and three-bedroom units and accessible, watchable play spaces designed into the buildings.

But the plans took turns that no one expected in the last 20 years. It got denser faster than anyone imagined. The Downtown South became the area that absorbed extra density for all kinds of things the city was trying to do, from saving heritage buildings to getting new arts spaces.

Many cities are trading the one resource they have — land — in exchange for city benefits, but no area has likely taken as much density in so little space as Downtown South.

Developers could get 10 per cent more space than normally allowed for their buildings if they bought heritage density — that imaginary space the city has created and given to building owners in historic areas like Gastown and Chinatown so they could sell it as a way of paying for restoration.

Developers also got extra density in return for providing the kinds of community services that the city couldn’t or wouldn’t pay for on its own: the VanCity theatre on Seymour in the Brava, the Contemporary Art Gallery in the Mondrian on Nelson, and space for a music school, Orpheum expansion, and 150-seat rehearsal studio in the Capitol Residences that will replace the old Capitol 6 theatre building on Granville.

That Capitol project set new records in the city’s density horse-trading. In exchange for the 46,000-square-foot music facility, and $1.89 million to operate it for 20 years, developer Rob Macdonald got 250,000 square feet more space than the 90,000 allowed by the zoning. The permitted tower height was increased from 300 to 414 feet.

But besides the density getting shoehorned in, development happened at a rate planners hadn’t expected. While megaprojects, with their marketing departments advising them on roll-out strategy, produced towers at even and predictable rates, the dozens of individual developers working in Downtown South just barrelled ahead pell-mell, outstripping the city’s ability to keep up.

Added to that, another strange thing happened: children started showing up in record numbers. Although city planners studiously insisted that developers build child-friendly places, everyone seems to have been surprised by the response. The latest census statistics showed there are around 600 children living in the area.

HIGH COST OF AMENITIES

Last May, central-area planner David Ramslie sent an almost desperate-sounding report to council. The city, he noted, had promised to provide 2.8 hectares of park space in the area. It had provided .53 hectares — the Emery Barnes Park, which is only one-half of the park that was promised for the area. And getting more space was increasingly problematic, with prices skyrocketing and land-hungry developers snapping up every square foot in the increasingly competitive downtown.

The city had planned to create 189 child-care spaces by last year. Only 74 had been created, while the waiting list for spaces throughout the downtown grew to 1,800 by last year.

The city had set a target of 688 units of social housing. Only 533 had been created.

In all, Ramslie concluded it would take around $80 million to provide the missing parks, child care, social housing, and street improvements this populous little area needed by 2021. In response, council approved a drastic 50-per-cent increase in the fees they charge developers to help pay for community amenities, up to $13 a square foot. But even the increased money doesn’t solve all problems.

FINDING SOLUTIONS

Behind the scenes, staff have also been taking extraordinary measures to try to muscle in some of those services.

City council, in a rare move, authorized staff to expropriate one piece of property on Seymour to help acquire all the land needed for the second half of Emery Barnes Park. As it turns out, the expropriation power hasn’t been used as the city’s real-estate department and the owner continue to negotiate.

To create daycare spaces, the city’s real-estate director, Mike Flanigan, has put a lot of pressure on developers to provide child care in their buildings. Henry Man of Magellan Developments is putting a 37-space daycare into his Atelier project at Homer and Robson.

Man admits he didn’t really want to. In spite of the considerable reward of extra floor space the city gave his project in return for building the daycare, Man says nothing really makes up for the complications that a daycare in a building brings, from the endless meetings to the architectural redesign required to comply with, for examples, rules about hours of sunshine for the outdoor play space. And it’s not even a marketing advantage, since he can’t promise buyers with children will get a space in the daycare, while buyers without children may be put off by the idea of a unit near what they fear will be a noisy area.

But Flanigan and his staff talked him into it. “At the end of the day, they were persistent.”

However, even the real-estate department can’t work its magic with the schools. The school built at the eastern end of the peninsula, Elsie Roy, has achieved the dubious distinction of being the only public school in the Lower Mainland, possibly in North America, where parents camp out overnight just to get their kids a spot in the regular kindergarten program.

The province’s education ministry is refusing to build the other elementary school planned for the area at International Village, saying there are empty spots in nearby Strathcona, on the other side of Main and Hastings — an option unlikely to entice people who moved downtown so they wouldn’t have to commute.

Gilda Philps, the head of the parent committee at Elsie Roy, says local realtors tell her the school crunch is a major factor. “Families are leery because of the school. If they can’t get in, they’re not sure they want to move here.”

There’s one other demographic that’s been part of the population explosion: the homeless.

“We didn’t anticipate we’d be dealing with the amount of homeless and mentally ill as we have been,” says planner Michael Gordon. Downtown South was home to a fair number of residential hotels. The city’s been performing contortions to replace them, but it can’t keep up.

That’s not surprising. Developers and marketers are having a hard time working out how to build something affordable for people who have incomes, let alone those without.

Tracie McTavish of Rennie Marketing calls the Downtown South “this undiscovered jewel in the downtown,” but says the skyrocketing real-estate and construction costs are making it increasingly difficult to build housing that regular Vancouverites can afford.

McTavish is working with one developer trying to build a tower next to the old Murray Hotel, which will be preserved as low-income housing next to the market condos. “We’re trying to make it affordable but these days, affordable just means really small suites,” said McTavish. As a result, Rennie Marketing is contemplating a building of 500-square-foot suites.

If that trend continues, that could mean even more people packed into the Downtown South than the 24,000 envisioned now.

Forget Hong Kong. Hello Manila.

© The Vancouver Sun 2008