New structure’s high grass will be sanctuary for downtown pests

Susan Lazaruk

Province

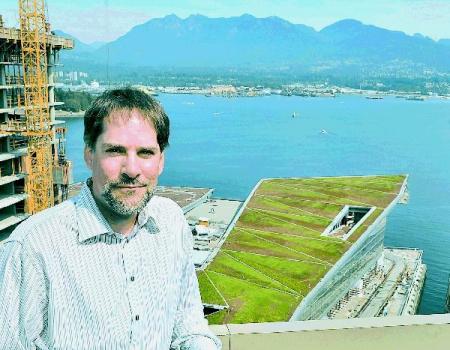

Landscape architect Bruce Hemstock stands above the green roof of Vancouver’s new convention centre. The environmental benefits of the roof include converting carbon dioxide to oxygen, insulating the building and helping bugs feel more welcome downtown. Photograph by : Jon Murray — the Province

With the completion next spring of the new convention centre in Vancouver‘s Coal Harbour, there will be a few blocks of new parkland added to the city — but they’re strictly for the birds and the bees.

The expansion project, west of the current convention centre, is being topped off with a 2.4-hectare green — or “living” — roof that covers the flat, sloping segmented roof, and will be the second-largest in North America, next to a Michigan Ford plant covered with grass patches.

About one-third of the roof area was planted in late April with 400,000 seedlings and thousands more seeds, and is sprouting patchy green fuzz like a giant, flat Chia pet.

Two dozen different coastal grasses — such as pearly everlast, nodding onion and field strawberries — native to B.C. were chosen because of their ability to withstand drought and draw birds and insects, said landscape architect Bruce Hemstock.

“They are relatively easy to maintain and they create the habitat for the type of species we want to attract,” he said.

Besides converting carbon dioxide to oxygen, insulating the building to keep heating and cooling costs down and reducing storm-water runoff, the green roof is designed as an ecological reserve.

“We want to promote bees, ants, other insects and birds to bring them back to the downtown,” said Hemstock.

Humans will be allowed to look but not touch.

“You can’t walk on it because then it becomes no more than a park and you lose all that [birds and insects],” he said. “I’ve seen swarms of honeybees up there already.”

The sloping meadows of roof can be seen from adjacent rooftops as well as from inside the centre through specially designed view planes and while walking north on Burrard and Thurlow streets, he said.

And visitors will be able to get up close to the grasses by accessing the 1,500-square-metre roof of an adjoining section of the building to be leased for commercial use.

The remainder of the convention centre’s roof, now covered with 15 centimetres of sand mixed with composted organic matter and lava rock carted up last winter, will be planted next month.

Landscapers left little to Mother Nature, designing the roof to withstand soil erosion from winds or heavy rains.

“Runnels” built diagonally throughout the roof are designed to mimic rivers to slow water runoff.

“We had a really big storm that lasted a week and a half and we had no loss of soil,” said Hemstock.

The choice of plants and lack of natural prey are expected to keep unwelcome species such as rats, Canada geese and seagulls away.

But Hemstock said weeds, which he prefers to call “volunteer species,” will be allowed to float on to the roof as long as they’re not too invasive. Dandelions are fine; knotweed is not.

“It’s self-maintaining and it will grow and change as the plants want to,” said Hemstock.

A 43-kilometre irrigation system, designed to conserve water, is fuelled by so-called black water, the building’s sewage that will be treated on site to a potable state. The auto-sensor is programmed to turn on if the plants wilt and only in the summer months.

No chemical fertilizers will be used and the grasses will be cut every fall and the clippings left for mulch.

If there are leaks in the 30-year membrane, the irrigation system’s auto-sensor will locate them for quick repair, said Hemstock.

© The Vancouver Province 2008