Vancouver, from the day the first train pulled in, has always done well by gatherings of outsiders

CLAUDIA KWAN

Sun

Who knew Expo 86 would transform Vancouver into George Wong’s ‘international city that’s incredibly livable?’ There simply wasn’t the knowledge, or the opportunity a quarter of century ago, to access it and analyse it. ‘You have to remember, back then, people were handing around cassette tapes. Unless you’d been to an exposition, people didn’t know,” observes Matt Meehan, a Concord Pacific executive. ‘It’s not like the electronic age now, where if you want to look at anything you can just go to the Internet.’ Below, fairgoers move into Expo 86 on the final day of the exposition, Oct. 13, 1986.

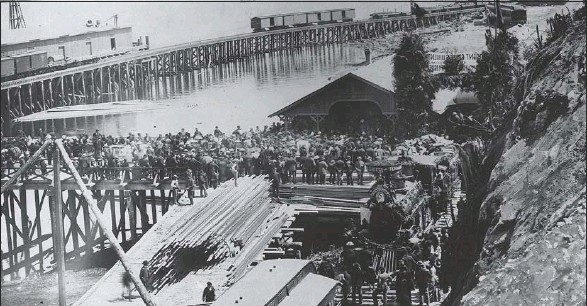

This image of the arrival of the first transcontinental passenger train in Vancouver on May 23, 1887 has served many purposes over the years. Its publication here illustrates continuities about Vancouver real estate over 125 years — the immigrant is a constant presence and that value has always been found along, and at the end of, transportation projects — local, national, international. Harry T. Devine (1865 – 1935) was the creator of this image and the lot-promotion image on today’s Westcoast Homes cover. The City of Vancouver archives is the source of the photos.

Will the Winter Games help or hinder the metropolitan Vancouver real estate market, or hardly have any affect? Opinion, of course, is divided. Who can know the future?

The past, however, suggests Vancouver real estate is simultaneously exceptional and unexceptional.

Advances and retreats in value, and supply and demand, occur here just as they do in any other metropolis.

But whatever occurs here occurs in a physically singular and culturally diverse geography and occurs because the living here is better than there, not cheaper, but better.

The first private sale of Canadian Pacific Railway land, in 1886, is illustrative of the course of the better-life attraction of Vancouver residency.

The buyer was Walter Graveley, a small-town Ontario native who had done well by real estate in Manitoba. When values there retreated, he came to British Columbia and never left.

He was a co-founder of the Royal Vancouver Yacht Club and lived long enough to be among those inaugural Vancouver voters who gathered at the old Fairmont Hotel Vancouver in 1936 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the city’s incorporation.

In 1886, Vancouver was already an ethnically diverse place.

In the 1881 census, Vancouver residents reported 20 different ethnic or national attachments; in 1891, even more.

Strathcona particularly emerged as a neighbourhood of working class residents, from China and Japan and Italy, followed by South Vancouver.

By the Great War, there was a genuine downtown skyline to the west of Strathcona, capped by the claims of first the Dominion Building, at Hastings and Cambie, and then the World Building, at Pender and Beatty, now better known as the Sun Tower, as tallest buildings in the British Empire.

The municipalities of Point Grey, South Vancouver, and Vancouver would amalgamate as the Great Depression was beginning in 1929. Even during that period the demand for housing continued, with apartment buildings appearing along Oak and Granville Streets and in Kitsilano.

Renting rather than home ownership became the norm in the late ’60s as affordability soared beyond the reach of many and a snapshot of the cityscape at the time reveals both low and highrise residential buildings in many areas. The shift to attached residency was noticeable by the middle ’70s with the Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver issuing guides on what the Strata Property Act meant for consumers.

Political unrest through the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East sent people to Canada, and a swell of immigration from South Asia began in the late 1970s.

But it was the influx of Hong Kong money leading up to 1997, and the end of Crown colony status there, that really demarcated a hugely visible influx of overseas investment.

“People flight and capital flight,” says George Wong of Magnum Projects, a veteran organizer of local real estate sales and marketing campaigns. “There are two reasons why people look for a safe haven for their families and their money, free from political instability.”

George Wong’s mother left China’s Hunan province in 1949, frightened by how her “bourgeois” family might be treated under Communist rule.

The family settled in Hong Kong, but tumultuous protests there against the Cultural

Revolution had her feeling unsettled again. In 1973, the family began looking overseas, well in advance of Hong Kong’s handover date to China in 1997.

“Some Hong Kong families were very forward thinking, they took the long view,” says Wong. “Vancouver was very attractive because it’s like the Switzerland of North America.”

Safe, stable, with an excellent quality of life and the advantage of being one direct flight away from Asia, Vancouver interested many. Generous rules around an ”investor” category smoothed the way for individual families to immigrate in the late ’20s and early ’90s, but also led to criticism that Hong Kong Chinese were ”buying” Canadian citizenship.

There were also rumbles of discontent over the perception the Hong Kong buyers had artificially inflated prices with their sudden influx of demand for residential property, or that they were absentee landlords, detrimental to the social fabric of individual buildings.

“The resentment, I think, came from the conspicuousness of the wave of spending,” says Wong.

Many immigrants from Hong Kong at the time chose to start fresh with their Canadian households, picking up an expensive car or two, furnishing sizable empty homes from top to bottom, or even tearing down existing houses to build new ones.

“It was obvious change that was too much, too fast,” Wong points out gently. “I don’t think Canadians are prejudiced, but it’s human nature to see a new element as an outsider. This is true even within sub-groups of the Chinese community.”

There could hardly have been a more conspicuous purchase by a Hong Kong presence than Li Ka-shing’s acquisition of the former Expo 86 lands on the north shore of False Creek, for $320 million.

Matt Meehan worked for the world fair and on the sale of the site to Li Ka-shing. Now a senior vice-president with Concord Pacific — the company developing the massive parcel of land — he remembers how people working on Expo knew it would be huge, even though the fair didn’t seem to register on public consciousness in the Lower Mainland until it was halfway over.

“You have to remember, back then, people were handing around cassette tapes. Unless you’d been to an exposition, people didn’t know,” Meehan says. “It’s not like the electronic age now where if you want to look at anything you can just go to the Internet.”

He believes the purchase and development of the Expo lands as one cohesive parcel was the catalyst for what has been dubbed Vancouverism: high-rises developed to complement natural landscapes and community-building amenities like parks and public space.

“If the Expo lands had been chopped up into five or six parcels, we never would have seen the number of parks we have in Downtown South,” Meehan says. “I remember when the Urban Fare [grocery store] went in at Davie and Marinaside, people really got a sense that there’s a neighbourhood here.”

He also remembers the concept of pre-sales — putting down a deposit on a condo not yet built — as being something in which Vancouver led the way for the rest of Canada.

“It was something quite familiar to Hong Kong buyers, but pretty foreign for others,” Meehan says. “It was quite a new thing to commit to buying a place just by looking at a floor plan, and then waiting a couple of years.”

The historical push to buy property in Vancouver has neither been limited just to residences nor to the Hong Kong market. Commercial real estate investment and development analyst Clare Stevens, now with the firm DTZ Barnicke, recalls a boom in selling fully tenanted office buildings in 1978.

“Companies needed space to house the baby-boomer workers,” says Stevens. “There was more European investment at that time, and purchases from large financial interests like SunLife and Great West Life Insurance.”

The 1982 North American recession put a severe damper on commercial real estate development, but it roared back by the late ’80s. However, Stevens says a change in tax policy in the early ’90s under the NDP scared away many international investors. The Asian financial collapse of 1997 also virtually eliminated investment from Japan.

In recent days, there have been nibbles from abroad, but “nothing solid,” Stevens says. He’s not expecting a boom in commercial real estate investment after the 2010 Winter Games, because he simply doesn’t see the demand for it in Vancouver.

George Wong of Magnum Projects says healthy residential real estate investment continued in the 1990s from the Taiwanese, and into 2003-2004 from mainland China. He says super ultra-high net worth individuals (i. e., the rich) from all over the world are continuing to buy Vancouver homes to serve as vacation properties. Some of that spending has in turn led to business-related investment, as the newcomers establish a feeling of connection to their playground.

“I think we’re an international city that’s incredibly livable, and that we’ve become a world resort destination,” Wong says with a smile.

Concord Pacific’s Matt Meehan takes it a little bit further, saying Vancouver’s success with livable neighbourhoods downtown is being studied with interest by many international cities.

“Expo 86 was a chance for the world to discover us,” he says. “Maybe the Olympics are a means for us to show the way.”

© Copyright (c) The Vancouver Sun