Andrew Fleming

Van. Courier

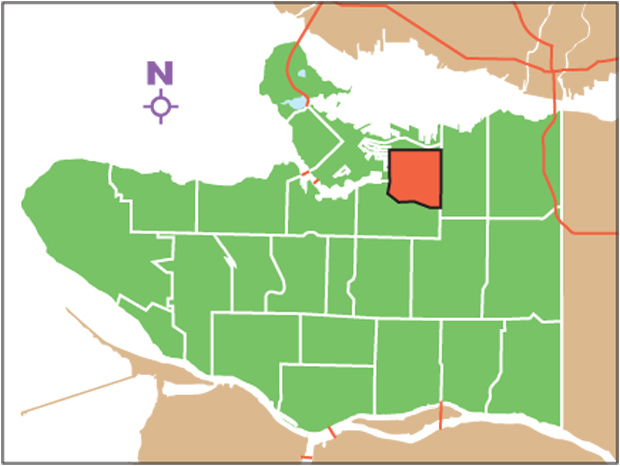

Sprawling more than seven square kilometres between Fraser and Nanaimo streets and from East 41st Avenue to Broadway (or East 16th between Fraser and Clark)

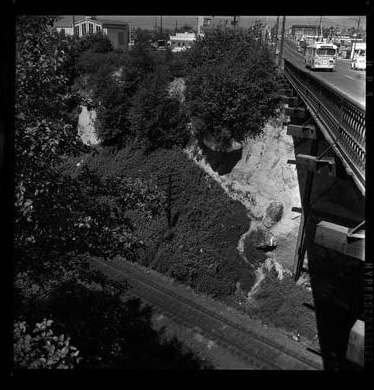

Trout Lake Cedar Cottage circa 1960. Photo: City of Vancouver Archives, COV-S511-: CVA 780-130

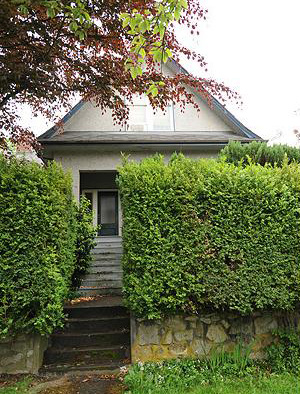

Trout Lake Cedar Cottage as it looks today. Photo: Andrew Fleming

View of the 2500 block of Commercial Street looking north from 20th Avenue, circa 1913. Photo: City of Vancouver Archives, AM54-S4:LGN 504

View of the 2500 block of Commercial Street looking north from 20th Avenue as it looks today. Photo Rebecca Blissett

The Cedar Cottage Brewery circa 1902. Photo: City of Vancouver Archives, James Skitt Matthews, AM54-S4:Dist P69

The Cedar Cottage Pub and coffee house as it looks today. Photo: Rebecca Blissett

The 3400 block of Commercial Street circa 1913. Photo: City of Vancouver Archives, James Skitt Matthews, AM54-S4-2: CVA 371-821

The 3400 block of Commercial Street as it looks today. Photo Rebecca Blissett

3286 Knight Street in 1908. Photo: City of Vancouver Archives, AM1376-: CVA 330-6

Approximate location of 3286 Knight Street as it looks today. Photo: Rebecca Blissett

Corner of Knight Street at Fleming Road, looking northwest circa early 1900s. Photo: City of Vancouver Archives, Timms family, AM1376-: CVA 330-19

Corner of Knight Street at 18th Avenue, looking northwest circa early 1900s. Photo Rebecca Blissett

Looking south at Commercial Street and 18th Avenue, early 1900s. Photo: City of Vancouver Archives

Looking south at Commercial Street and 18th Avenue as it looks today. Photo: Rebecca Blissett

The Robson Memorial Methodist Church, built in 1907, at Fleming Road and Flett Road in 1908. Photo: Vancouver City Archives, Timms family, AM1376-:CVA 330-9

St. Mark’s Lutheran Church was built in the mid 1920s after the Robson Memorial Methodist Church burned down in 1921 at Fleming Road and Fleet Road. Photo: Rebecca Blissett

Customers get pampered at Kingsway’s Orchid Beauty Centre this past Friday morning. The Kensington-Cedar Cottage business is recognizable by its turquoise-painted storefront. Photograph by: Rebecca Blissett

Kensington-Cedar Cottage is a difficult neighbourhood to pin down. Sprawling more than seven square kilometres between Fraser and Nanaimo streets and from East 41st Avenue to Broadway (or East 16th between Fraser and Clark), it has close to 50,000 people who call the ‘hood home, more than nearby standalone cities such as Port Moody or West Vancouver.

One problem is that many people don’t refer to it as Kensington-Cedar Cottage. Even on the City of Vancouver’s new $3-million website, the area is often referred to simply as Kensington, which is generally considered the section south of Kingsway that was named for an historic British palace – which is why nearby streets have such regal names as Windsor, King Edward and Prince Albert. And, just as people often misidentify John Hendry Park as Trout Lake Park – Hendry was a former lumber baron who used the lake for his mill and his descendants later donated the land – most people refer to the Cedar Cottage district simply as “near Trout Lake.” The area was originally named Cedar Cottage after a former train stop, itself named for, you guessed it, a nearby cedar cottage.

The entire region south of 15th Avenue was known as South Vancouver until its amalgamation into Vancouver in 1929, and the intersection near Kingsway and Commercial Street was a main hub due to its proximity to the lake.

The neighbourhood is now one of the most ethnically diverse in the city, with only a third of residents claiming English as their mother tongue. An equal number speak Chinese as their first language and it is also home to the Croatian Cultural Centre, the German community’s ersatz Alpen Club and the annual Philippine Pinoy Fiesta parade, Latin Summer Fest and National Aboriginal Day celebrations.

Despite KCC’s Britannic nomenclature, the culture it is now most closely associated with is Vietnamese. Two years ago, a group of local residents – primarily first- and second-generation “boat people” who escaped by sea from the Vietnam War and settled nearby – successfully petitioned city council to rename a section of Kingsway Little Saigon.

Kensington-Cedar Cottage: Neighbourhood by the Numbers

15.9: In millions of dollars, the final cost of the new Trout Lake rink and community centre, roughly three times more than the original estimate the City gave before the 2003 Olympic plebiscite.

28: Number of years since the Public Dreams Society first began hosting Illuminares Lantern Festivals at John Hendry Park. The non-profit arts group recently announced this year’s event would be their last due to lack of funding.

3,000: Approximate number of signatures on a 2011 petition presented to city council requesting the creation of a special Little Saigon business district on Kingsway Avenue.

22: Number of individual bronze sculptures by artist Tom Dean, including a rather terrifying leopard having its ear gnawed by a goat, located outside the new Kensington library branch.

7: Number of halls or meeting rooms available to rent for special events at the Croatian Cultural Centre.

17: Number of storeys of a residential tower at King Edward Village, built by the Aquilini Group and completed in 2008, the neighbourhood’s tallest building.

100: Age of the redeveloped Charles Dickens elementary school, the first school in the Vancouver school district to meet LEED environmental standards.

84: Units of E. coli per 100 millilitres of water, as measured by Vancouver Coastal Health in Trout Lake on Aug. 9. The amount is the third highest in the city but much lower then the now-closed Second Beach and Sunset Beach.

1: Number of KFC outlets in KCC.

0: Number of trout in Trout Lake

Kensington-Cedar Cottage: Rebranding of Kingsway area to ‘Little Saigon’ attracting …

by Jennifer Thuncher

Drive along Kingsway Street towards New Westminster, blink and you’ll probably miss Vancouver’s Little Saigon, which encompasses the area between Fraser and Knight streets.

Made up of myriad shops and eateries, the strip officially became Little Saigon in May to little mainstream media fanfare but much local ceremony after a neighbourhood campaign that included a petition signed by 3,000 in support of recognizing the contribution made to the area by Vietnamese residents.

The May 12 event was marked by speeches and a parade attended by Mayor Gregor Robertson and several fellow council members, including Vision Vancouver Coun. Kerry Jang, who in 2011 put forward the motion to council to brand the area.

Three months after the area’s official rebranding, Jang said so far the response from Vancouverites “has been great.”

As in similar officially sanctioned Vietnamese communities across North America, a Little Saigon street sign and branded banners run the length of the strip.

Chris Lien, owner of the popular Tung Hing Bakery on Kingsway for more than 10 years, said he has seen a lot of changes in the make up of his neighbourhood over the last decade and is “ambivalent” about the designation.

“I have seen quite a lot more tourists because it has been called Little Saigon,” he said, but with the increase in tourists he has also seen more problems with garbage and parking.

Singling out the Vietnamese community for recognition aroused more decided opposition. A “Stop Little Saigon” petition signed by 100 local residents circulated and some residents continue to question the attention given to one group over others. Ambrose Oba-Underwood, who has lived in Kensington-Cedar Cottage for more than 12 years, has no qualms with the Vietnamese who live and work in the area, but feels the special designation could be “discouraging to non-Vietnamese businesses.”

He would have preferred no branding at all as a more inclusive option for his community, he told the Courier by email.

Oba-Underwood said it has been a sensitive issue for him to speak publicly about and the reaction from some has been “ironic.”

“[With] a few people branding me a racist due to the fact that I don’t support branding an area racially,” he said.

According to Jang, the Little Saigon christening was an entirely grassroots movement spearheaded and sustained by the people of Vietnamese heritage who live or own businesses in the area. And it “didn’t cost the city a penny” because the Little Saigon supporters raised all the money themselves for everything from the May party to steel clamps holding the street banners to the poles, said Jang.

Jang said there are also plans for a monument in the community to recognize the sacrifices made by the refugees from Vietnam who came to Vancouver in the 1970s with very little and went on to make a life for themselves and for the next generation.

Vietnam‘s Saigon, known as Ho Chi Minh City since the close of the Vietnam War, is the country’s largest city. The city has gone by various names over time. From the French conquest in the 1860s, to 1975 and the communist takeover after the war it was officially known as Saigon, which is a Westernized version of a previous name. Other official Little Saigons can be found in California, Texas and Melbourne, Australia.

Kensington-Cedar Cottage: Vietnamese nail salons dominate Kingsway

Orchid Beauty Centre attracts clientele of all backgrounds, ages

Sandra Thomas

The exterior of Orchid Beauty Centre on Kingsway Street in Kensington-Cedar Cottage is a colourful mix of turquoise-green vinyl siding, a pink door and purple writing. And while the odd-looking building could be easily mistaken for a garden shed, it’s actually one of the most popular nail salons on Kingsway Street.

Just moments after the front door opened last Friday, women of every nationality, age and demographic began trickling through the door. And while at 10 a.m. there were only three employees tending to a handful of customers, by 11 a.m. there were eight staff members painting toes, scrubbing feet or applying artificial nails to seven women, while as many sat waiting for their turn for a salon treatment.

Owner Anna Ly opened the shop 13 years ago and from the number of clients frequenting the salon on this day, it was obviously a wise decision. Ly also owns a second Orchid Beauty Centre location on East Broadway and recently celebrated the grand opening of a third shop on Lougheed Highway in Burnaby.

Ly immigrated to Canada from Vietnam with her husband and young daughter in 1991, first moving to New Brunswick before heading west to Edmonton and finally settling in Vancouver. Lyn had her second child and then in 2000 opened Orchid Beauty Centre on Kingsway.

The entire length of Kingsway has no lack of nail and beauty salons, including Ngoc & Nga Beauty Salon, Jenny Hair Design, Shed O Beauty Care, Wendy Hair Salon, and Bianca’s Hair Salon and Boutique, but they’re particularly prevalent in and around the business district now officially known as “Little Saigon,” the stretch of street between Fraser and Knight streets. It’s there where you’ll find Orchid Beauty Centre at 1298 Kingsway.

According to Aprodicio Laquian, professor emeritus with the Centre for Human Settlements Community and Regional Planning at the University of B.C., it’s no coincidence the majority of nail and beauty salons along Kingsway, and even across North America, are operated by Vietnamese owners.

“Like China, Vietnam uses an internal passport system called ‘ho khau‘ that controls migration,” Laquian wrote in part in an email to the Courier. “As the country’s economy boomed, cities needed more workers so the ho khau was relaxed and millions of peasants flocked to the cities.”

Laquian noted that while the population of Hanoi, Vietnam’s capital, increased from 2.7 million in 1999 to 6.5 million in 2009, the majority of migrants did not have technical skills so barber shops and beauty and nail salons boomed. He added these “informal sector” jobs were exported as former Vietnamese residents moved abroad.

“The migration of rural folks to cities also applies to the proliferation of pho or noodle shops not just in Vancouver, but in other countries,” said Laquian. “I was in Hanoi, Hue, Hoi An, Da Nang and Saigon [Ho Chi Minh City] recently and mostly subsisted on delicious pho from street vendors.”

He added the fact Vietnamese rule the world of nails and beauty in North America is likely not cultural.

“It could be as simple as a Vietnamese group cornering the market for nail salons, the purchase of equipment, facilities, training programs, like South Asians cornering the taxi business or the Vietnamese cornering the corner store business in New York,” said Laquian.

But for Orchid Beauty Centre owner and Vietnam transplant Ly, it’s more than a matter of culture or practicality that drives her every day.

“I love Vancouver,” said Ly, while filing a customer’s fingernails. “And I love what I do.”

© Copyright 2013