Kelly Sinoski

Sun

Arthur Erickson in 2002. Photograph by: Stuart Davis, Vancouver Sun files

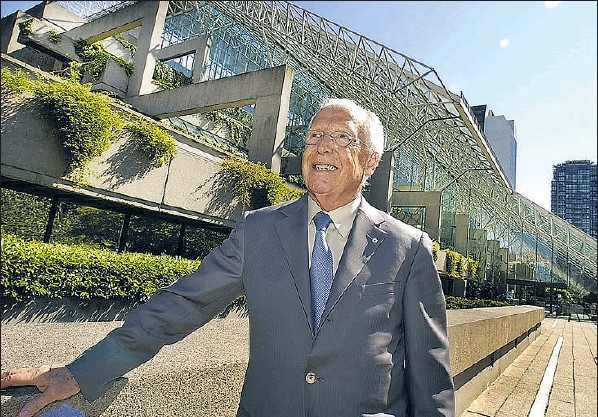

Arthur Erickson, pictured in 2004 in front of the Vancouver Law Courts, which he designed. The world-renowned architect’s creative vision never stagnated, and he incorporated new ideas in his work until the end, says his friend Gordon Smith. — BILL KEAY/ VANCOUVER SUN FILES

Internationally renowned Vancouver architect Arthur Erickson, who mingled with the world’s artistic, corporate and political elite during a career that lasted more than half a century, has died at age 84.

His long-time friend, artist Gordon Smith, said Erickson had suffered from Alzheimer’s and was living in a nursing home when he died Wednesday. “He’s my oldest friend. I’m going to miss him dreadfully and I know a lot of people will,” Smith, 90, said in an interview. “Arthur was one of the great Canadians. He wasn’t just a good architect — he was a great man.”

Smith, who met Erickson in the war and hung out with him at landscape painter Lawren Harris’ house listening to records, said the world will be mourning the loss of one of Canada’s most famous artists.

He recalled how Erickson, at age 22, exhibited his abstract art at the Vancouver Art Gallery. He then went on to McGill University to to study architecture, leaving behind a legacy of architectural masterpieces around the globe.

He first achieved international acclaim for his award-winning design for Simon Fraser University, before designing mansions, libraries, universities and other massive buildings.

But Smith, who worked on projects with Erickson in Osaka and Washington and has known him for 60 years, said he will always remember one of the first homes Erickson designed — on an outcrop in Horseshoe Bay for Smith and his wife Marion — in 1953.

That home was demolished in 2007, but a second one commissioned by the Smiths in 1965 still stands.

“He was a world-class architect; he had every honour in Canada and was the only Canadian to ever get the gold medal in the states for architecture,” Smith said. “He did it for the love of it, he was passionate about it. He was always a visionary, he looked forward.”

Erickson never dwelled on the past, Smith said. He appreciated young architects and incorporated new ideas and modern trends into his designs up until the end.

His work speaks for itself: the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia, the Canadian Chancery or embassy in Washington, D.C., and the San Diego convention centre and California Plaza.

When he was in his late 70s, Erickson accepted a plea by a non-profit organization to design the Portland Hotel, a Downtown Eastside housing complex, for poor people with histories of drug abuse and mental illness.

Erickson said at the time the social housing project was more interesting than building condominiums for the wealthy.

“He was an artist architect; he had that creative approach to making art,” Smith recalled. “He was respected across the world.”

Although Erickson enjoyed accolades and honors from his professional peers, he suffered the public humiliation of personal bankruptcy in 1992, after piling up more than $10 million in debt.

That financial disaster almost made the mansion-maker homeless. At that point, his Point Grey cottage was his only declared asset.

But Erickson rebounded. He started up another Vancouver-based architectural firm and went on to design bold new buildings like the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, Wash. and the Liu Centre for the Study of Global Issues at UBC.

Erickson might have been one of the elder statesmen of world architecture, as some admirers have described him, but he was not always diplomatic. He frequently railed against those who dared to change his original designs during major refits. “It’s very difficult to see your children wasted,” he said late in life.

In 2004, when Erickson was 80, a controversial address that he made to Canadian bankers in 1972 was one of two speeches he kept posted on his corporate web site.

After declaring that worldwide tourism was the greatest threat to human cultures and slamming bank-financed “multi-storied monster” hotels in pristine Third World settings, Erickson reminded the bankers of their enormous responsibilities.

“You, as bankers, cannot afford to be concerned with only the economic aspects of projects that you finance,” he declared.

“There may be serious implications on the natural environment, on the urban environment, on human culture, which at some future time may even be considered crimes against mankind.” • The complex life of a self-described non-conformist began in 1924, in Vancouver.

Erickson shared stories of his childhood with Edith Iglauer, author of a 1981 biography, Seven Stones: A Portrait of Arthur Erickson, Architect.

Erickson’s father lost both legs during a First World War battle. When he returned from the war, his fiance went ahead with the wedding despite his disability. She explained, according to Iglauer, that she would “rather marry a man with wooden legs than a wooden head.”

Their son, Arthur Charles Erickson, began painting at age 13, using National Geographic photos to paint two small fish on his bedroom wall. At 16, he exhibited some of his oil pastel abstracts at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

In 1942, when Canada and other Allied nations were fighting Germany and Japan, Erickson was taking second-year courses at UBC. At the urging of his father, he joined the Canadian Army University Corps and studied engineering before being asked to take a Japanese-language course. Erickson was in India, headed to Malaysia as a commando in a behind-Japanese-lines field unit that was supposed to bombard the enemy with demoralizing Japanese-language propaganda, when U.S. atomic bombs fell and Japan surrendered. So he ended up with a far less dangerous assignment: program director for Radio Kuala Lumpur.

By 1946, Erickson was back in Vancouver, taking economics, history and Japanese courses, aiming for a career in diplomacy. But his goal changed one year later, when he looked through Fortune Magazine and saw photographs of American architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s desert house, Taliesin West.

“Suddenly, it was clear to me,” Erickson wrote in his 1988 autobiography, The Architecture of Arthur Erickson. “If such a magical realm was the province of an architect, I would become one.”

After four years of study at the school of architecture at McGill University in Montreal, Erickson visited the already-famous architect’s home. Wright invited Erickson to stay at Taliesin for a year of study, but Erickson accepted instead a one-year travelling scholarship from McGill. With the help of an $800 veteran’s grant and a free passage on an Indian freighter that was carrying dynamite, he made that $2,500 scholarship last almost three years.

Erickson’s travels followed the history of western architecture, from Egypt and Lebanon, from Greece to Spain, from southern to northern Europe. He worked in London for the architect son of legendary psychologist Sigmund Freud before returning home.

In Vancouver, he worked for several large architectural companies and was fired from two.

“I would have fired me today,” he told Iglauer. “I was looking at things too differently . . . Really, I was a dreamer and not much use. I wasted a lot of their money.”

In 1952, Erickson began working with architect Geoff Massey, designing houses for friends and wealthy customers. His first patron, the son of a lumber magnate, commissioned the 1958 Filbert House, at Comox on Vancouver Island.

Erickson began teaching architecture in 1955, at the University of Oregon. One year later, he started teaching at UBC, where he would challenge undergraduates with open-ended, Socrates-style assignments until 1964.

Erickson said he reached a landmark moment in his career in 1963, when he and Massey won a competition to design a new Burnaby Mountain campus for the then-non-existent Simon Fraser University.

Unlike other North American universities that gave departments their own buildings, they designed a campus of linked buildings.

“What Simon Fraser says is that the body of knowledge is one, and that to artificially segregate different disciplines and incarcerate them in different buildings completely disallows the kind of cross-fertilization, the chance associations, that have always occurred in our great institutions of knowledge,” Erickson wrote.

That design ignored the competition rules, but Erickson worked on it for weeks. Although Erickson and Massey didn’t expect to win, they attended the award ceremony, just to see the winning design. Seventy other designs were submitted, but the judges were unanimous: Erickson and Massey won first prize and became responsible for the university’s overall design.

To many students and staff, the vast columns of grey, unadorned concrete were repressive. Erickson called concrete “the marble of our time.” International awards and other big commissions followed.

In 1965, J.V. Clyne, the chairman of MacMillan Bloedel, asked Erickson to design a new corporate headquarters in downtown Vancouver — the 27-storey building now on Georgia Street.

The University of Lethbridge, designed in 1968, stretched a long, nine-storey building atop an Alberta coulee, a series of hills and ravines.

In the local press, scribes were now calling Erickson the city’s leading architect and quoting his pronouncements. In 1967, for instance, he warned citizens that a proposed freeway along Vancouver’s waterfront would destroy the natural features that made the city beautiful, just as freeways had destroyed the heart of Seattle.

“We can’t afford to keep sacrificing the assets of the city for the sake of traffic,” Erickson said.

Another time, he told The Vancouver Sun that Vancouver was a “hick town.”

“There are a few attempts to put up good buildings, but mostly the plan is to get something up and get what you can out of it,” he said. “I blame the city government for this, to a large extent. They have no respect for the consequences. Any building can go up, with any finish. There is no teeth in the design committee [at city hall].”

In 1989, Erickson declared Vancouver should plan for a regional population of 10 million and stop pretending it is a suburb. (Erickson didn’t say when the region’s population, now at about two million, which grow to 10 million.)

Meanwhile, Erickson’s corporate empire grew. There was an office in Montreal for Expo 67 projects, which included the Canadian Pavilion. More offices opened in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia in the late 1970s for projects in the Middle East. At one time, he was designing a massive water garden in Baghdad for Iraq’s then-president Saddam Hussein — a project abandoned when the long Iraq-Iran war began.

In 1972, B.C.’s first New Democratic Party government shelved a Social Credit government plan to construct a 55-storey government office in the heart of downtown Vancouver. It gave Erickson an opportunity to turn his notions of good urban design into reality. Erickson’s scheme, unveiled the following year, became Robson Square and the Law Courts. Instead of another office tower, the offices and the courts were laid on their side to become a lower-profile, three-block-long complex. Instead of a narrow hallway between courtrooms. The glass and steel truss roof created a wide public gallery — a place, the design plan stated, that would be “inviting public awareness and involvement in matters of justice.”

The Museum of Anthropology at UBC became another Vancouver landmark when it opened in 1976.

Visitors enter a Great Hall graced with tall cedar totem poles and one of the world’s most outstanding collections of West Coast aboriginal art. The mythic carved creatures face a gargantuan wall of glass with views of a replica aboriginal village perched on the cliffs of Point Grey. Progressively larger post-and-beam columns of concrete frame that stunning view.

“The museum should reassure our Indians of the greatness of their culture, and perhaps give them back some of their dignity and confidence, which was taken away by conquest, then, more humiliatingly, by welfare,” Erickson said.

Erickson’s other works in Canada include the Sikh Temple in Vancouver, the Bank of Canada headquarters in Ottawa, Roy Thomson Hall in Toronto and King’s Landing condominium and office development on Toronto’s waterfront.

In other countries, he designed the Canadian Chancery or embassy in Washington, D.C., the San Diego convention centre and California Plaza, a massive office complex in Los Angeles.

But Erickson’s business faltered. He closed down his Toronto office in 1989 and his Los Angeles office in 1991, angering unpaid creditors, who began filing lawsuits. Some former employees said Erickson was constantly shuffling between his projects, travelling around the world, and often reversed work that had been done in his absence.

Erickson said he was simply a bad businessman.

“You know, there’s a phrase, idiot savant,” he told The Sun. “I think I fall into that category. You’re very good at one thing, but an absolute moron in others.”

In 1992, Canada’s best-known architect filed for personal bankruptcy, listing more than $10.5 million in debts. The only asset he listed was his 600-square-foot cottage in Point Grey — a pond-and-garden-dominated refuge he bought in 1957 for a mere $11,000. When Erickson sought the court’s protection because he couldn’t pay his bills, the house was worth about $450,000, and the subject of a court-ordered sale.

Erickson walked away from his debts but managed to remain in his Vancouver home. Supporters formed a group called the Arthur Erickson House and Garden Foundation, which became the registered owner of a property that now has an assessed value of more than $1 million. And the man who hobnobbed with the rich and famous began renting his former property.

He set up shop again, as the Arthur Erickson Architectural Corporation. From a small cluster of second-floor offices above a storefront just west of Granville Island, the consulting practice worked on large-scale planning projects, as well as plans for waterfronts, coastal developments and town centres.

Erickson’s new office wasn’t in one of his monuments. It looked down on the Molson Brewery parking lot, but the view windows faced north, to the high-density, inner-city False Creek neighbourhood Erickson had envisioned decades before.

On his company’s website, Erickson posted a kind of mission statement for all to see:

“Architecture, as I see it, is the art of composing spaces in response to existing environmental and urbanistic conditions to answer a client’s needs. In this way, the building becomes the resolution between its inner being and the outer conditions imposed upon it. It is never solitary but is part of its setting and thus must blend in a timeless way with its surroundings yet show its own fresh presence . . .

“We are not peddlers of the fashionable. We believe that good design defies fashion, is truly innovative, eminently sensible, yet a source of inspiration to those who have the pleasure of living with it.”

© Copyright (c) The Vancouver Sun